COVID-19: What can we learn from history?

20 May 2020

Blog

When I began writing this blog, I mentioned that the current economic crisis had no precedent in modern history and that I hadn't found any examples of economies voluntarily closing in the way so much of the world had chosen to simultaneously. I still haven't. However, while the economic crisis we are facing may be unique, pandemics themselves are not. In this post I want to look back at previous episodes of widespread diseases to see if we can draw some lessons for today, and for the future.

Focusing on the economy, there are a number of ways in which pandemics can have an effect. On the supply side, output and production will be affected if workers fall ill, or if, even without containment measures, they choose to minimise their exposure to infection by reducing their time spent at work if they can afford to. On the demand side, consumers are likely to increase precautionary saving and spend less, particularly on activities that require closer social interaction. We have witnessed both of these factors at play over the past few months.

Robert Shiller has also outlined that, aside from the COVID-19 pandemic, "a pandemic of anxiety about the economic consequences" can also arise. This pandemic of "financial anxiety" can take on a life of its own and we need to be aware of such potential amplifiers of the real economic effects of COVID-19. Clear and calm communication is essential at this time.

A key point for me looking at the historical evidence is that the oft-mentioned trade-off between the lockdown measures and economic growth is overstated. It is the pandemic that has prompted these measures and without them, there would still be an economic downturn and an even worse public health emergency.

The actions taken by governments and policymakers in response to COVID-19 aim to learn the lessons of history and minimise the devastation caused by pandemics.

Economic Shocks

Economic shocks are not unusual and are something that we are always trying to prepare for, essentially by building resilience during good times. However, as Jerome Powell (Chair of the U.S. Federal Reserve) said last week, the current shock we are facing is not caused by the "usual suspects", such as high inflation or asset price bubbles. Indeed, although there have been flu pandemics in 1957/1958 and 1968, in my view we have to go back a century to the 1918 Great Influenza to find the most recent and relatively close historical comparison to our current situation.

A number of studies have analysed the economic effects of past epidemics, including the 1918 influenza, and the Bank for International Settlements has recently provided a very useful review of this area of research. One of the key takeaways from this work is that previous epidemics had long-term economic effects through sickness and loss of life. Of course, the containment measures in place around the world aim to mitigate these effects.

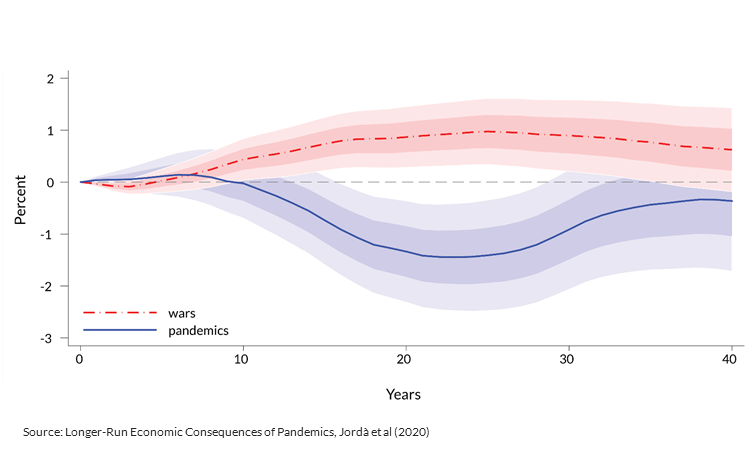

A particularly interesting piece of research from Jordà et al. (2020) assesses the longer-run economic consequences of pandemics using a historical data set reaching back to the 14th century. The authors find that pandemics have effects that can last for decades; for example, the natural rate of interest remains depressed for about four decades after a pandemic (for a sample of European countries). The natural rate of interest is the real interest rate which balances the supply of savings with the demand for investment while maintaining stable prices. Central banks have a particular interest in the natural rate of interest: if interest rates are below the natural rate, spending and borrowing can increase above levels consistent with what is happening in the economy and, similarly, if rates are above the natural rate, there may be excess savings which can result in reduced consumption. Jordà et al. find that pandemics reduce the natural rate, due to high death tolls and the subsequent fall in the labour force, which has wider economic effects, such as potentially greater precautionary savings. Wars, in contrast, have the opposite effect on the natural rate: it is higher than would be the case in the following decades, likely due to the need to rebuild physical infrastructure following the devastation that wars bring.

Figure 1: Response of the European real natural rate of interest following pandemics and wars

Source: Longer-Run Economic Consequences of Pandemics, Jordà et al (2020).

It remains to be seen whether these results hold for the current shock we are facing. The lockdown measures which have been introduced globally are unprecedented and are designed to prevent a loss of life similar in scale to previous pandemics. From an economic perspective, this may mitigate some of the longer-term economic effects, by protecting the labour force for example. For Ireland, John FitzGerald recently outlined the increases we are likely to see in household savings due to the pandemic. How these type of issues evolve in the coming years will have significant effects on the economy. In a world of already low interest rates, this will be of particular importance for monetary policymakers in the coming years.

Costs of Pandemics

The economic costs of pandemics have also been estimated by researchers. Correia et al. focus on the US and find that the 1918 influenza reduced manufacturing output by almost 20%. Importantly, the authors compare cities across the US and find that those who introduced containment measures, such as school closures or bans of public gatherings, did not fare worse economically than those who didn't. In fact, they find that these cities recovered more strongly after the pandemic, which suggests that aside from the primary goal of the measures – protecting the health of citizens – in the medium term, the containment measures may have a positive economic effect compared to the alternative.

Barro et al., in their analysis, estimate that the 1918 influenza resulted in falls of 6% and 8% in GDP and consumption respectively. Their estimates for deaths from the influenza suggest that 40 million people died, equivalent to 2.1% of the world population at that time. A similar outcome today would result in 150 million deaths. The containment measures put in place around the world aim to prevent the death toll approaching anything like this scale of devastation.

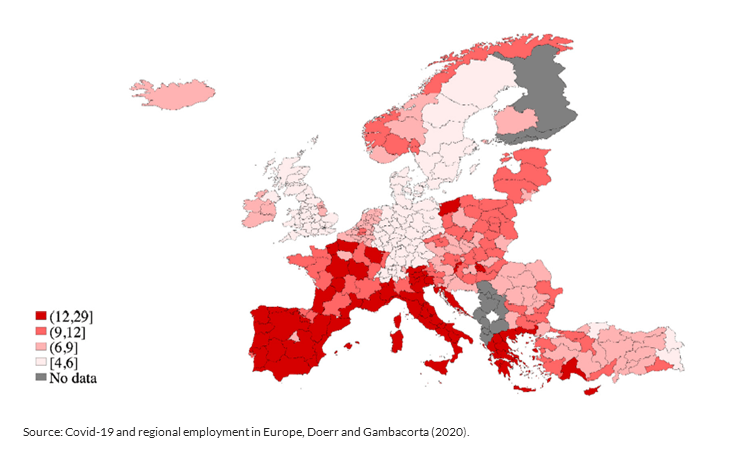

We must, of course, always be careful about the external validity of historical studies but there are insights for the impact on economic activity through both supply and demand channels, and the impact of the measures to address the pandemic (so-called non-pharmaceutical interventions, or NPIs). I have said before that I expect the impact on the Irish economy from COVID-19 to be significant. The demand side effects of the pandemic will continue for some time to come as the economy gradually reopens. On the supply side, while we are not the most exposed in Europe (see Figure 2), we certainly have significant numbers employed in vulnerable sectors.

Figure 2: Employment Risk Index

Source: COVID-19 and regional employment in Europe, Doerr and Gambacorta (2020).

Some Current Areas of Focus

After seeing through the initial shock of the pandemic, and the associated dislocation in markets, our attention is now turning to wider, more medium term issues.

For example, the longer the virus persists, the bigger the underlying shock to cash flows for companies and households and the likelihood that liquidity pressures will turn into solvency pressures.

Related to this, is the duration, size and type of support available and availed of by businesses and households. These will not only determine the strength of the economic recovery, but also the extent to which viable companies (and their employees) avoid default. But we know they are temporary and will have to be unwound in the near term.

The longer the virus stays with us, the greater the scarring effects of the crisis and the longer the economy will take to return to its potential.

A potentially significant scarring effect for Ireland and the world is the impact of COVID-19 on global interconnectedness. The last period of "de-globalisation" took place from about the beginning of the First World War up until the end of the Second World War. A host of factors were at play here, as outlined by the Peterson Institute for International Economics, with the 1918 influenza among them. The connections that have been built since 1945 should mean that global trade is unlikely to fall by as much in the coming years as it did during the 1914-1945 period but any decrease in openness will have consequences for Ireland. As a small, open economy, we are particularly exposed to developments in the global economy. Although some of the multinationals resident in Ireland have proven more resilient than others to the COVID-19 shock, they are not immune to global economic developments. And any structural changes from the shock – for example, to reduce the complexity of global supply chains – could impact the Irish economy.

Other risks that existed pre-COVID-19 are also occupying my mind, in particular the impact of the UK's withdrawal from the EU. As I said back in February, it seems likely that any future economic relationship between the EU and the UK will have more hurdles than the status quo, and that consumers, businesses and regulators should expect and plan for more frictions and divergence. The economic impact of the new trading arrangements will depend on how far they are from existing ones but it is likely to crystallise at the same time as the effects of COVID-19 are being felt.

All of these risks can transmit to the financial system and influence its ability to support households and businesses if not managed carefully. Our next Financial Stability Review will outline our full risk assessment for the Irish economy in more detail.

Conclusion

So, to sum up, I see at least three lessons that we can draw from history: (1) the impact of pandemics can have long term structural effects that we may not be able to identify for some time after the event; (2) the short term economic costs from pandemics can be severe but containment measures are necessary and without them we would still face an economic downturn with an even worse public health emergency; and (3) the most important lesson is that protecting lives is the overriding economic priority.

Although we cannot make the costs of the pandemic disappear, all of us are looking to minimise their impact and protect the community.

Gabriel Makhlouf

Read more