Introductory statement by Director of Economics and Statistics Mark Cassidy at the Select Committee on Budgetary Oversight

27 February 2019

Speech

Chairman, Committee members, good afternoon. I welcome the opportunity to appear before you today. I am joined by John Flynn, Head of the Irish Economic Analysis Division, and Thomas Conefrey, Manager of Structural Macro-modelling, also from the Irish Economic Analysis Division. I will give a brief summary of the outlook for the economy and the macroeconomic forecasts set out in the recently published Central Bank Quarterly Bulletin.

Chairman, Committee members, good afternoon. I welcome the opportunity to appear before you today. I am joined by John Flynn, Head of the Irish Economic Analysis Division, and Thomas Conefrey, Manager of Structural Macro-modelling, also from the Irish Economic Analysis Division. I will give a brief summary of the outlook for the economy and the macroeconomic forecasts set out in the recently published Central Bank Quarterly Bulletin.

The Irish economy grew at a strong pace in 2018, supported by the strength of activity on the domestic side of the economy and a relatively favourable international growth environment. While headline GDP growth last year was distorted by the activities of multinational enterprises, the evidence from a range of domestic spending and activity indicators is that the domestic economy grew robustly in 2018. We estimate that growth in underlying domestic demand last year was around 6 per cent. The strength of domestic activity has been underpinned by continuing strong and broad-based growth in employment, which has stimulated incomes and supported the growth of consumer spending, while the growth of key domestic components of investment, such as building and construction, has also accelerated.

The Latest Forecasts

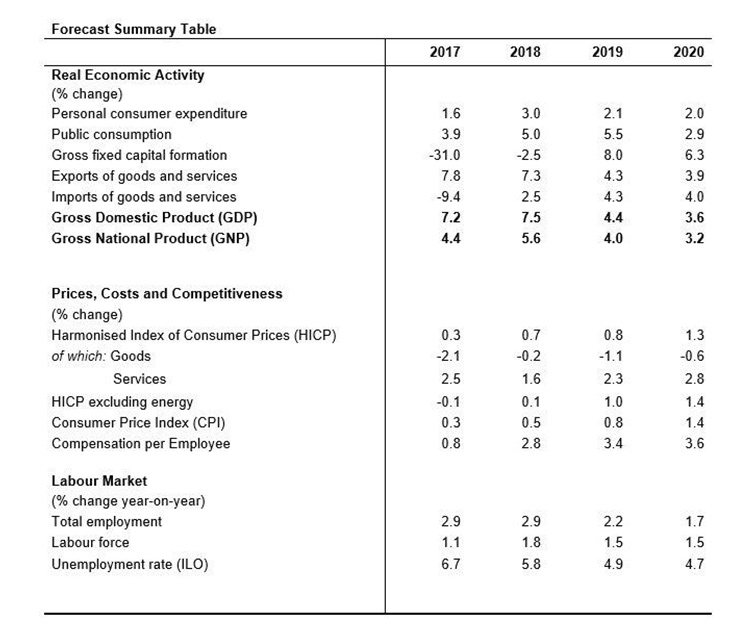

Looking ahead, the Central Bank’s latest forecast (shown in the attached table) is that, if a disorderly ‘no deal’ Brexit scenario can be avoided, the outlook for the economy in coming years remains broadly positive, though with some moderation in growth in prospect. We now expect economic growth this year of 4.4 per cent with a moderation to 3.6 per cent next year. This moderation partly reflects the projected impact of a less favourable and more uncertain international economic environment, with prospects for growth in our main trading partners having been lowered in recent months, and also some dampening impact from the uncertainty associated with Brexit. It also partly reflects the limits imposed by domestic capacity constraints due to the tightening of conditions in the labour market.

The latest published forecasts also represent a modest downward revision compared to our previous Bulletin which was published in October. Exports, private consumption and investment are weaker than previously expected while following Budget 2019 the contribution of government consumption to economic growth this year is stronger.

The main impetus to growth in coming years is expected to come from domestic demand, driven by further growth in employment and incomes, though some moderation in employment growth from current rates is projected. Reflecting the moderation in employment growth, and with some uncertainty about economic prospects weighing on sentiment, the growth of consumer spending is projected to ease towards 2 per cent over this year and next.

While overall investment has been quite volatile in recent years, primarily reflecting the activities of multinational enterprises, some key domestic components of investment, such as building and construction have rebounded strongly. While this growth is forecast to continue, the outlook for some other components, such as machinery and equipment investment is more mixed, reflecting some negative impact from increased risks and uncertainty. Taken together, the growth of underlying investment spending is expected to moderate.

Given the outlook for consumption and underlying investment, the growth of underlying domestic demand is also projected to moderate and grow by 4.1 per cent this year and by 3.3 per cent next year.

On the external side, while exports grew strongly in 2018, with projected growth in trading partner countries being revised downwards, some moderation in export growth is also projected, with exports forecast to grow by 4.3 per cent this year and 3.9 per cent in 2020. With Brexit-related uncertainty weighing on demand, the weakness in the UK market, evident last year, is likely to persist.

Turning to the outlook for the labour market, while moderation in the pace of employment growth in line with the outlook for aggregate demand is forecast, growth of 2.2 per cent this year and 1.7 per cent next year is set to exceed growth in labour supply of about 1.5 per cent in both years. As a result, the unemployment rate is projected to drop from an average of 5.8 per cent last year to 4.9 per cent this year and 4.7 per cent in 2020. As has been the case for some time, gains in employment have been broad-based, with employment growing strongly in many parts of the services sector and construction. In the central forecast, growth in employment, while moderating, will continue to be relatively broad-based.

Given the outlook for employment, we also expect a further pick up in wages which, combined with expectations of modest inflation, should translate into higher real incomes and purchasing power for households. We are forecasting the average increase in compensation per employee to increase from 2.8 per cent last year to 3.4 per cent this year and 3.6 per cent in 2020.

Brexit and the Economic Outlook

Turning to Brexit, we have previously published work examining the potential medium term impact on the Irish economy of both an orderly transition to a World Trade Organisation scenario and an orderly transition to a Free Trade Area type agreement such as the current Withdrawal Agreement. In the latest Bulletin, using our economic modelling tools, we also examined the possible macroeconomic implications of a sudden and disorderly Brexit on the outlook for the Irish economy. Given the unprecedented nature of a ‘no deal’ Brexit scenario, quantification is highly uncertain and this exercise represents a scenario analysis and not a forecast, in that it looks at what could happen under certain assumptions, not necessarily what is most likely to happen.

With a disorderly Brexit, significant additional frictions and costs arise. These result not only from the introduction of new trade arrangements, but also from a breakdown in some of the arrangements that make trade possible - for example, as a result of regulatory and customs issues, border infrastructure issues and legal uncertainties. This would be likely to have immediately damaging consequences for trade and the functioning of supply chains for production, distribution and retailing. Models and forecasting tools can be used to estimate the impact of long-run changes to trade arrangements, but are less suited for predicting the short-run effects and potential disruption arising from a breakdown in those arrangements - the scale of which would also be influenced by the ability of firms and retailers to adjust to any new arrangements, as well as any policy responses or mitigating actions taken as a result.

Nevertheless, it is clear that a ‘no deal’ scenario would have very severe and immediate disruptive effects, which would permeate almost all areas of economic activity. Certain sectors and regions would be disproportionately affected, particularly agriculture and food sectors as well as Border regions and other rural regions with a heavy reliance on agriculture and a particular reliance on the UK as an export market.

We estimate that a disorderly Brexit could reduce the growth rate of the Irish economy by up to four percentage points in the first year. Given the current favourable forecasts for the economy as a result of domestic demand and the strong non-UK multinational sector, our assessment is that there would still be some positive growth in output this year and next even under a ‘no deal’ scenario, but materially lower than in the central forecast - closer to one per cent growth in both years.

Brexit is not the only risk to the Irish economic outlook and other material domestic and external risks persist. On the domestic side, while some moderation in underlying domestic demand is in prospect following a period of strong growth, labour market conditions are still set to tighten further. As the economy moves closer to full employment, there is a need to continue to guard against the risk that strong cyclical conditions give rise to overheating dynamics. On the external side, in addition to Brexit, there continue to be some clear downside risks facing the Irish economy. The international economic outlook has weakened since the publication of the last Bulletin, while risks related to international trade and taxation persist. Given the position of Ireland as a small, highly open economy and the important role of multinational firms within the economy, changes in global trade, taxation and currency conditions have an important bearing on the performance of the economy.