Transcript of the video Quarterly Bulletin 4 2025 Irish Economic Outlook (PDF 131.75KB)

Comment

After showing notable resilience through 2025, the outlook for the Irish economy over the near to medium term is being shaped by divergent sectoral performances, ongoing structural change, geopolitical tensions and policy actions at home and abroad. Externally-focused multinational sectors are adapting to a changing international environment for trade and investment, and so far that adjustment has been relatively benign for Ireland. Signals for domestically-focused activity over the forecast horizon are more mixed, with data pointing to a slower pace of growth and higher inflation. These developments underscore the challenges for sustainable improvements in living standards arising from supply-side constraints, and the need for domestic policy to ease those constraints in a careful, well‑sequenced way.

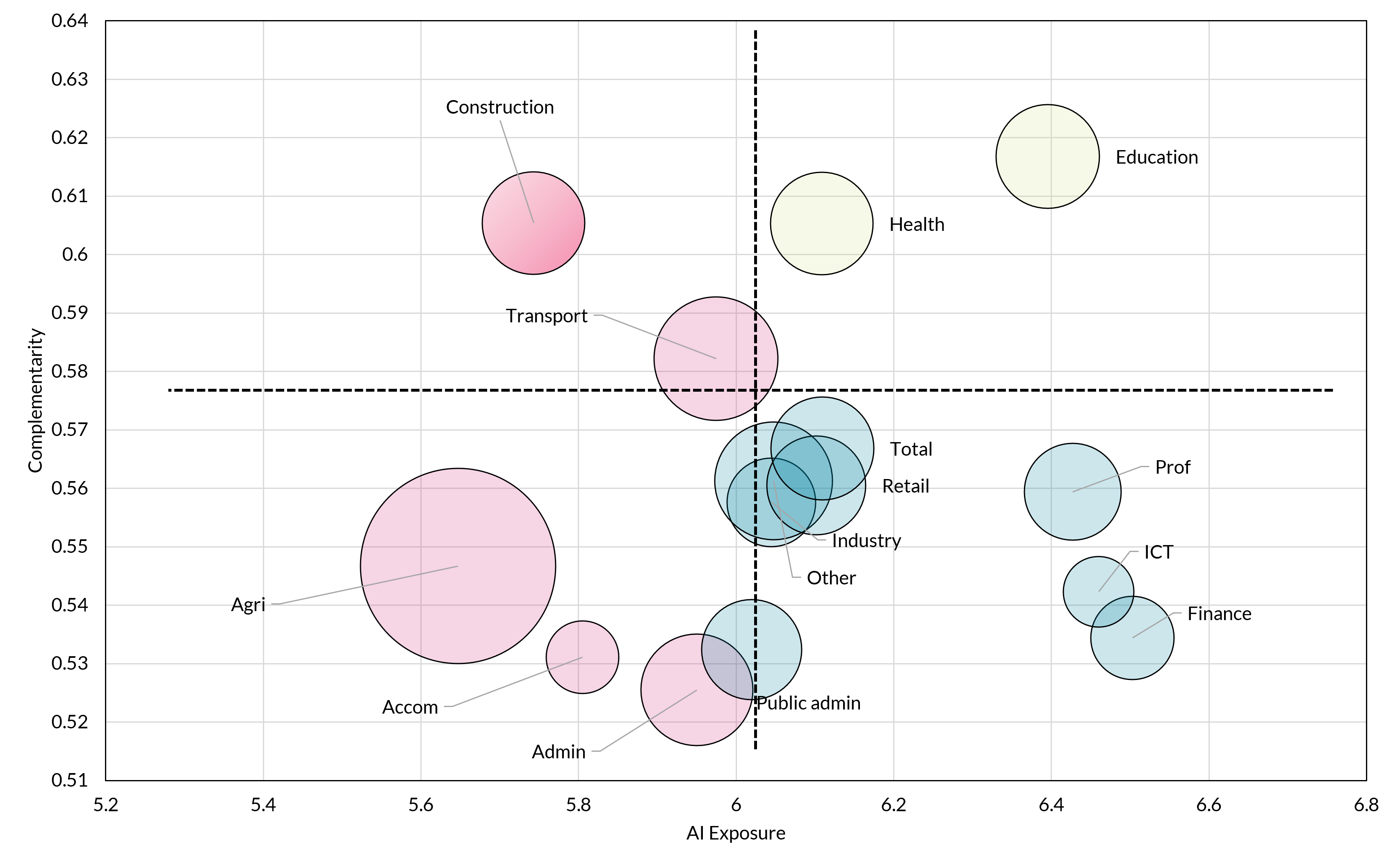

The adaptability of MNEs to a shifting EU–US trade and investment relationship - most evident in pharmaceuticals - remains a central driver of Ireland’s headline economic indicators. Much still depends on how this adaptation continues in the months ahead. Ireland remains a major hub for producing frontier, high‑demand medicines, yet firms have announced intentions to change pricing polices across their markets and their related value‑chain management and investment strategies, often in reaction to policy pressures and in bespoke arrangements with authorities. This could lead to greater volatility in headline GDP and alter the pattern of the volume and value of activity located in Ireland relative to elsewhere in the pharma value chain, with knock‑on effects for profitability and corporation tax receipts. Meanwhile, the ICT services sector - another major global sector with a significant presence in Ireland - both enables and is being reshaped by rapid advances in AI. Creating conditions for the Irish‑resident ICT sector and the wider economy to benefit sustainably from this transformation is increasingly important in a more fragmented global landscape.

As a small, highly globalised economy, Ireland’s prosperity will always be influenced by its attractiveness to foreign direct investment. Yet developments in the domestically-oriented economy and indigenous exporters are decisive for long‑term, sustainable growth in employment and living standards. Gauging domestic performance is challenging given frequent revisions to National Accounts data and the influence of MNE investment on even “modified” activity measures (Box A). Nonetheless, after several years of operating above potential, momentum in the domestic economy is easing, reflected in lower employment growth and a slower pace of activity in domestic sectors. This is broadly consistent with an economy facing significant capacity constraints, and it reinforces the need to improve supply‑side conditions that ultimately determine the domestic economy’s capacity to deliver sustainable gains in living standards.

The positive gap between labour demand and supply has narrowed as employment growth has slowed but remains relevant over the medium term in some sectors. A strong labour market has supported growth in average wages, real household disposable incomes and consumer demand since 2023, and this is expected to continue, albeit at a more moderate pace.

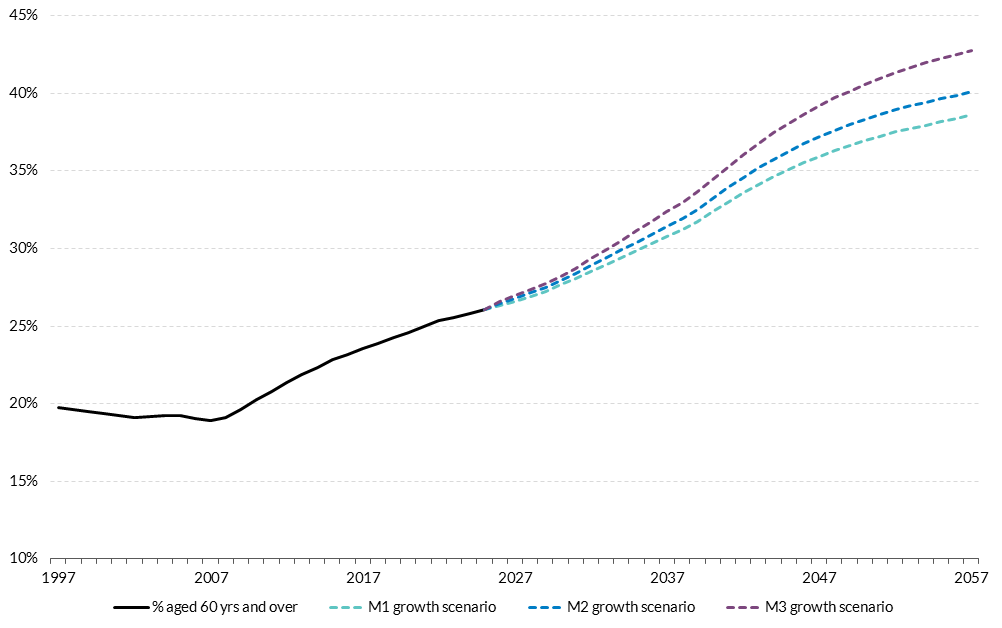

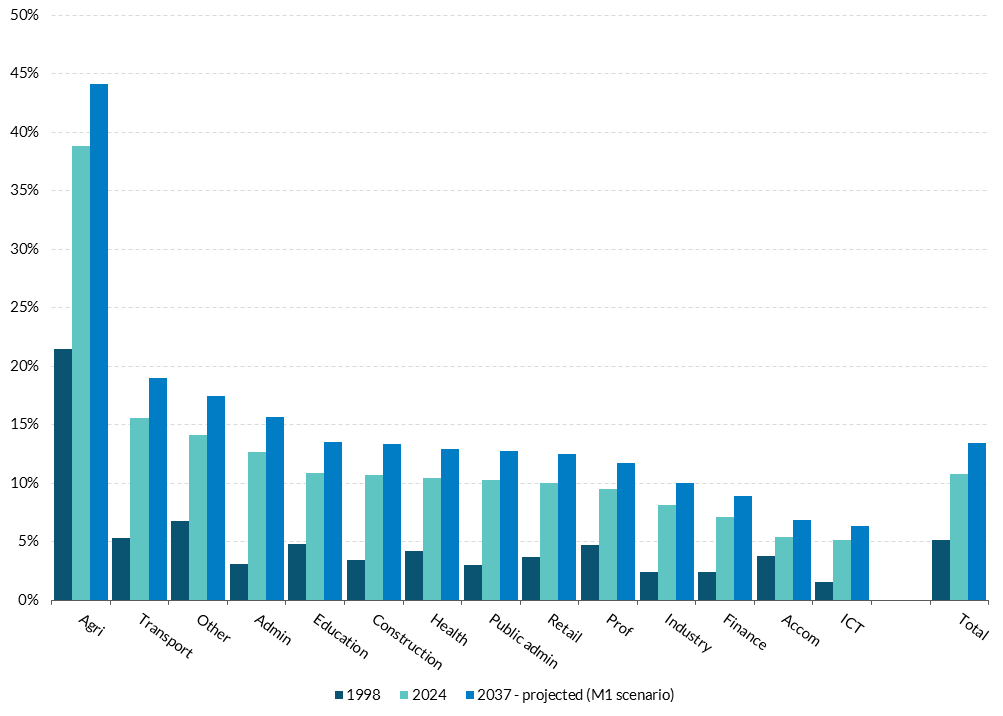

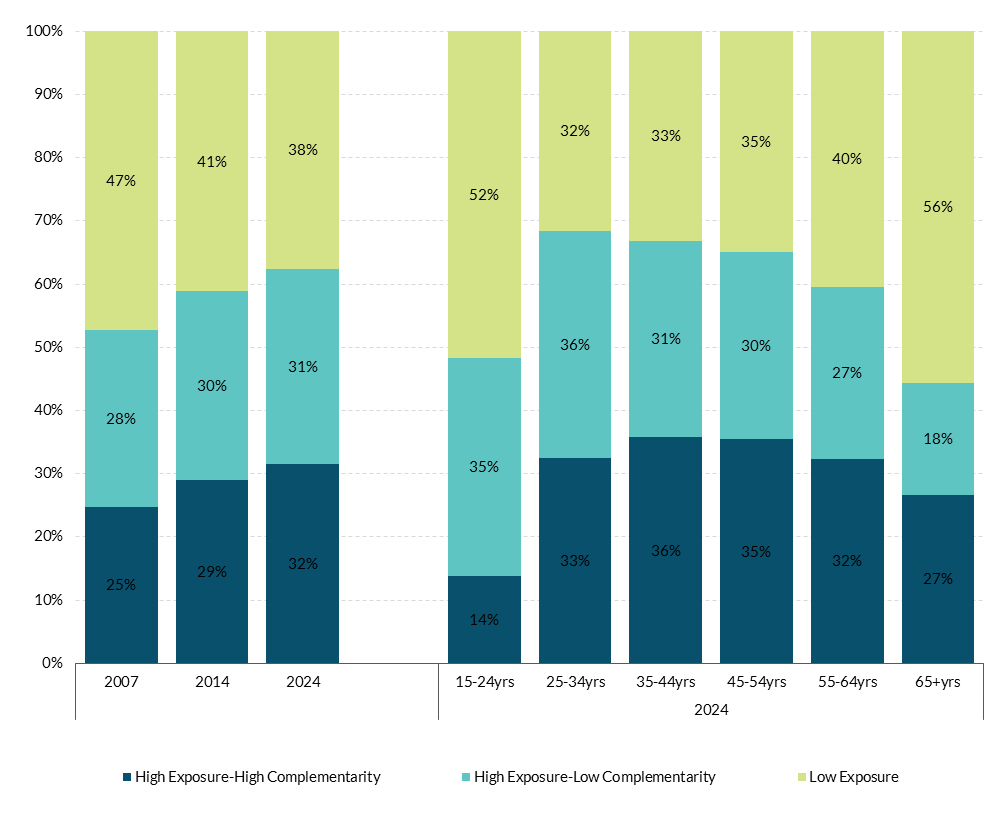

If infrastructure and housing needs are met at the scale envisaged in our forecast to 2028, domestic demand should retain momentum. Sustaining, if not prudently increasing that momentum requires careful macroeconomic management, including implementing structural reforms that reduce delays in delivering enabling infrastructure and maximising the use of available, serviced land for housing in areas of high demand. Recent initiatives such as the Accelerating Infrastructure Action Plan are welcome in that respect. Supporting appropriate technology adoption in delivering housing output will boost productivity and limit the ultimate labour demand in a construction sector that needs to expand. In the labour market more generally, new technologies, particularly AI, can complement or substitute some skills and occupations; others are less amenable to AI adoption, and yet other new skill requirements will emerge. Over time, these technologies will interact with the labour force’s demographic profile, potentially creating shortages in necessary skills (Box B). A forward-thinking approach to migration and measures to increase participation among older workers can help align technological progress and demographic change with sustainable, long‑term improvements in living standards.

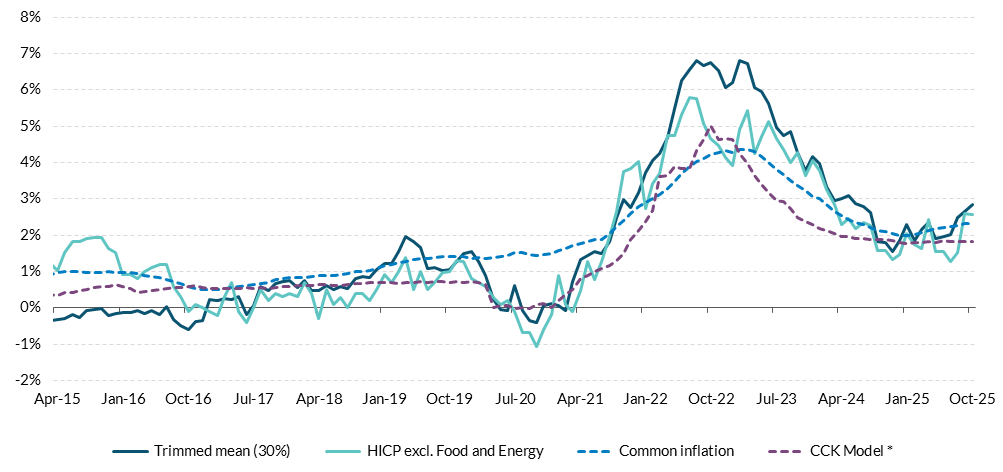

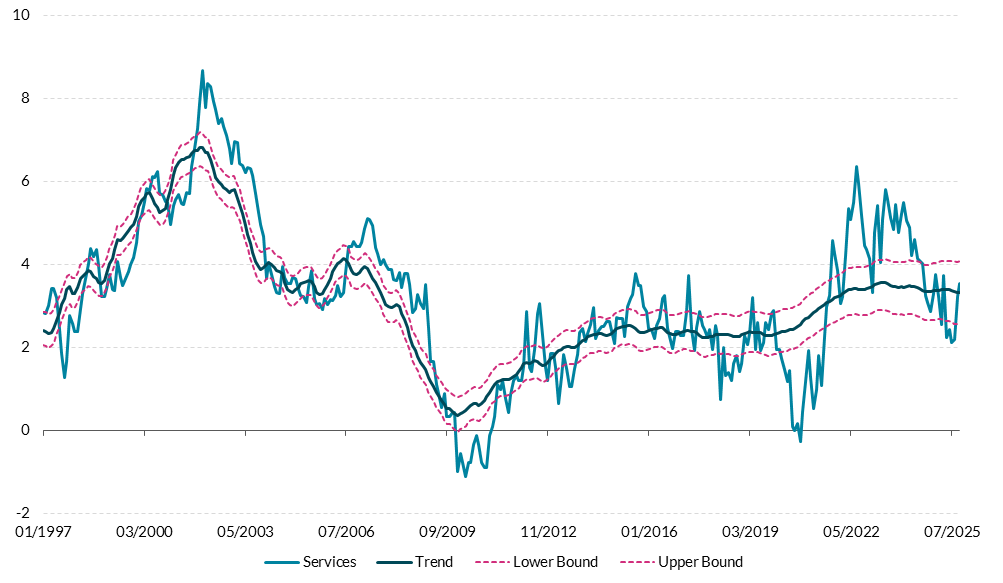

The expected rise in the share of domestic activity of traditionally non‑traded, lower‑productivity sectors, like construction, increases the risk of domestically-generated inflationary pressures and heightens the sensitivity of inflation to external price shocks. Policies that improve labour supply and raise productivity can mitigate those risks. Consumer price inflation eased significantly after the surge that followed Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Since early 2024, product‑specific movements in goods prices—energy price reductions last year and stronger food price increases from early 2025—have influenced HICP dynamics, but underlying services inflation has remained relatively strong, consistent with robust domestic demand. Trend services inflation appears to have settled into a persistently higher phase post‑Covid, at around 3 per cent, and higher than any period since 2007. This is occurring even though construction - typically a lower‑productivity sector - accounts for only 5.5 per cent of output in domestically dominated sectors, compared with 10 per cent in 2007. The more domestic activity relies on lower‑productivity sectors, the greater the risk of higher inflation, underscoring the need for careful macroeconomic management of the necessary expansion in construction activity and for actions to improve the productivity of the sector itself.

At its meeting in December the Governing Council decided to keep the three key ECB interest unchanged, meaning the main policy rate – the deposit facility rate – was maintained at 2 per cent. This decision was informed by the latest staff projections for the euro area, including that inflation is expected to stabilise at the 2 per cent target over the medium term. The Governing Council continues to follow a data-dependent and meeting-by-meeting approach to evaluating the appropriate monetary policy stance.

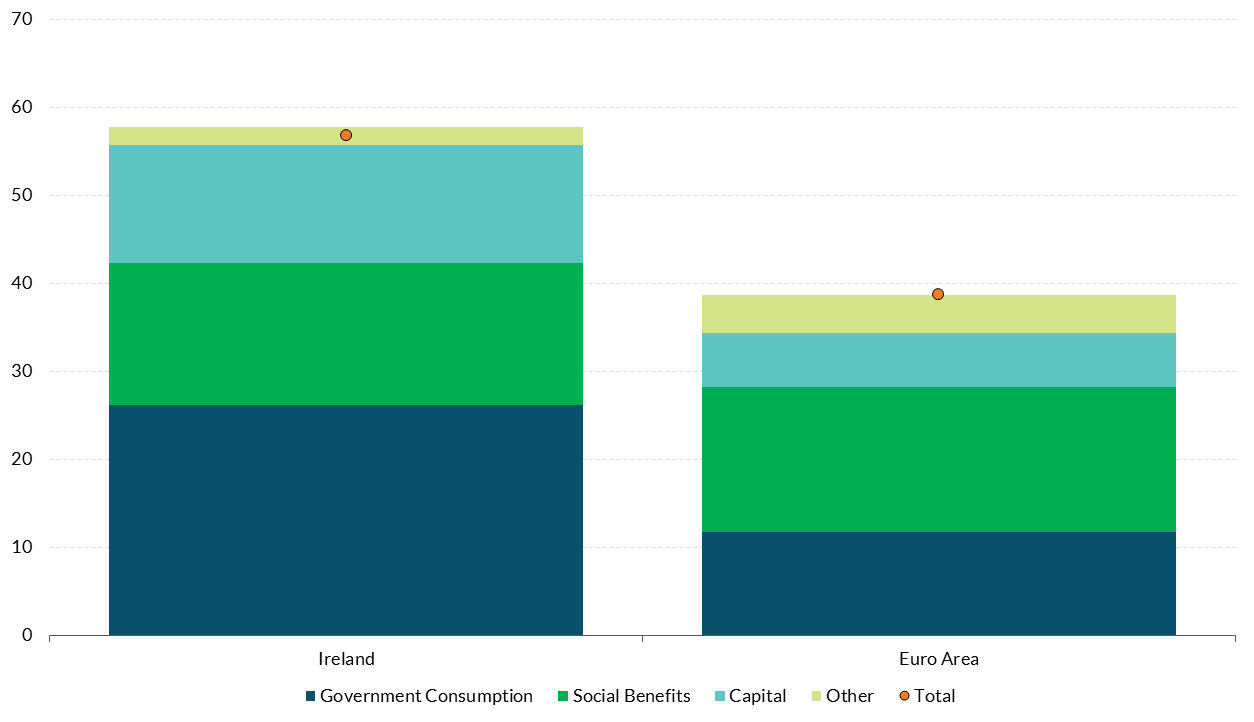

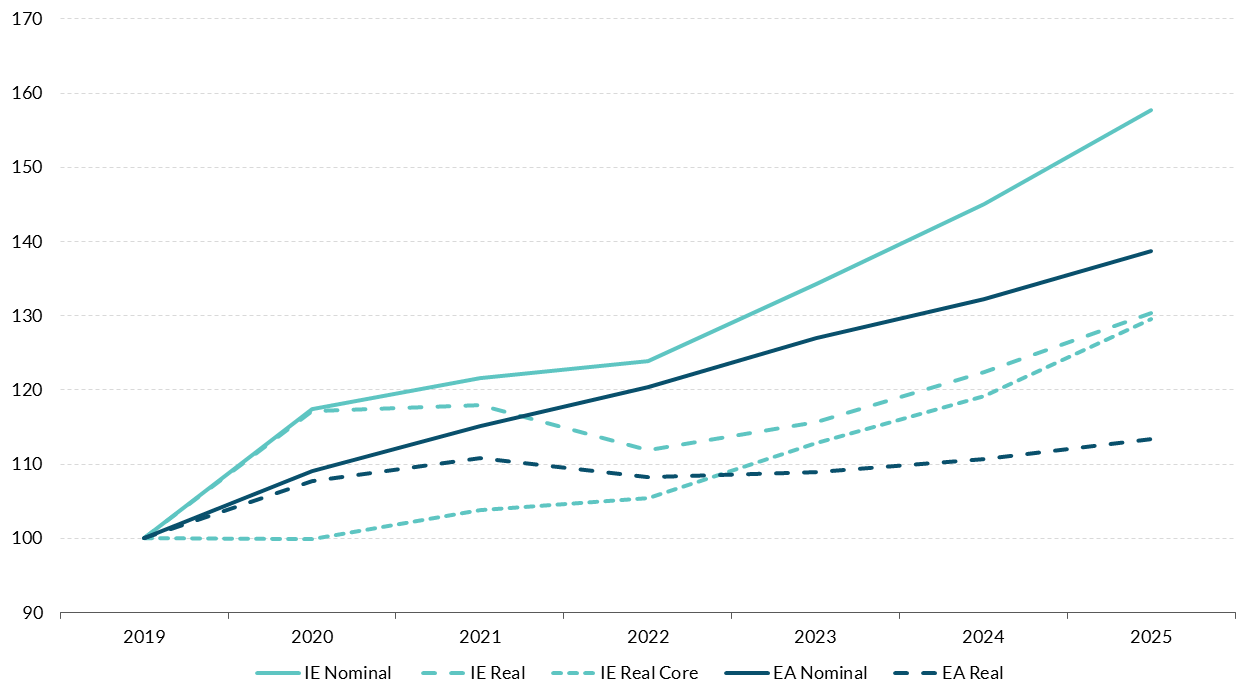

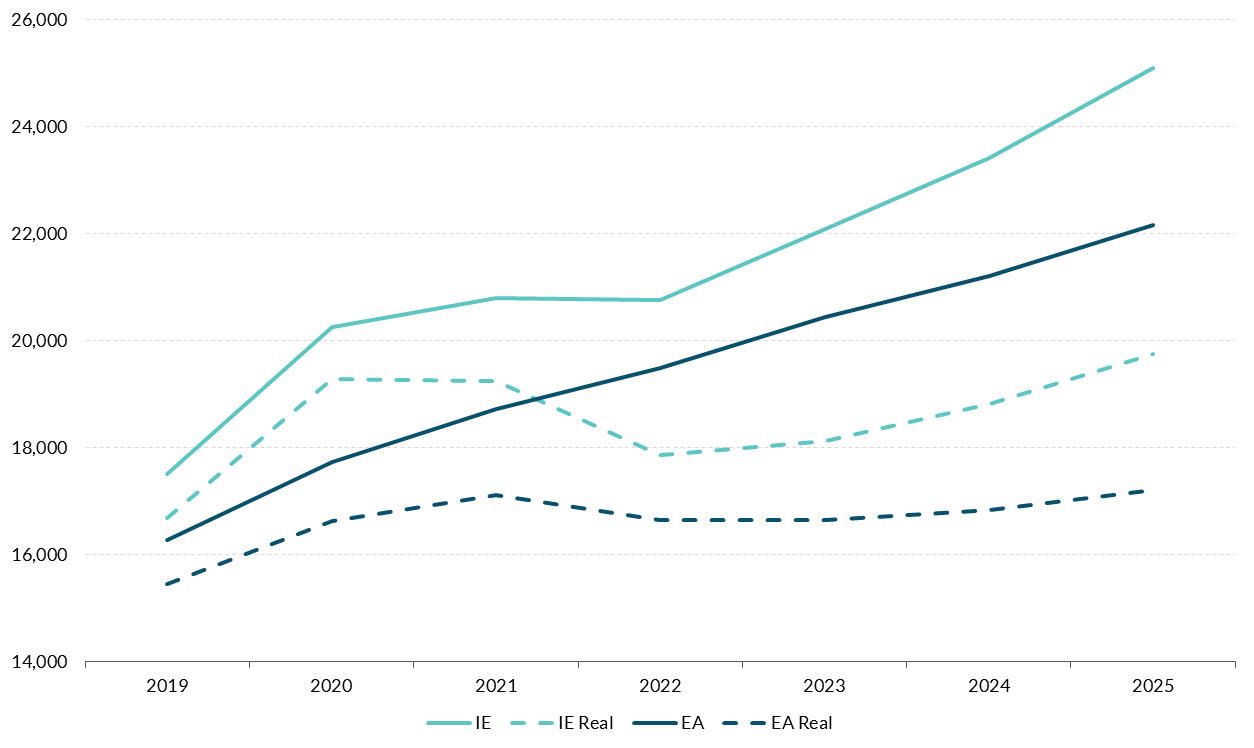

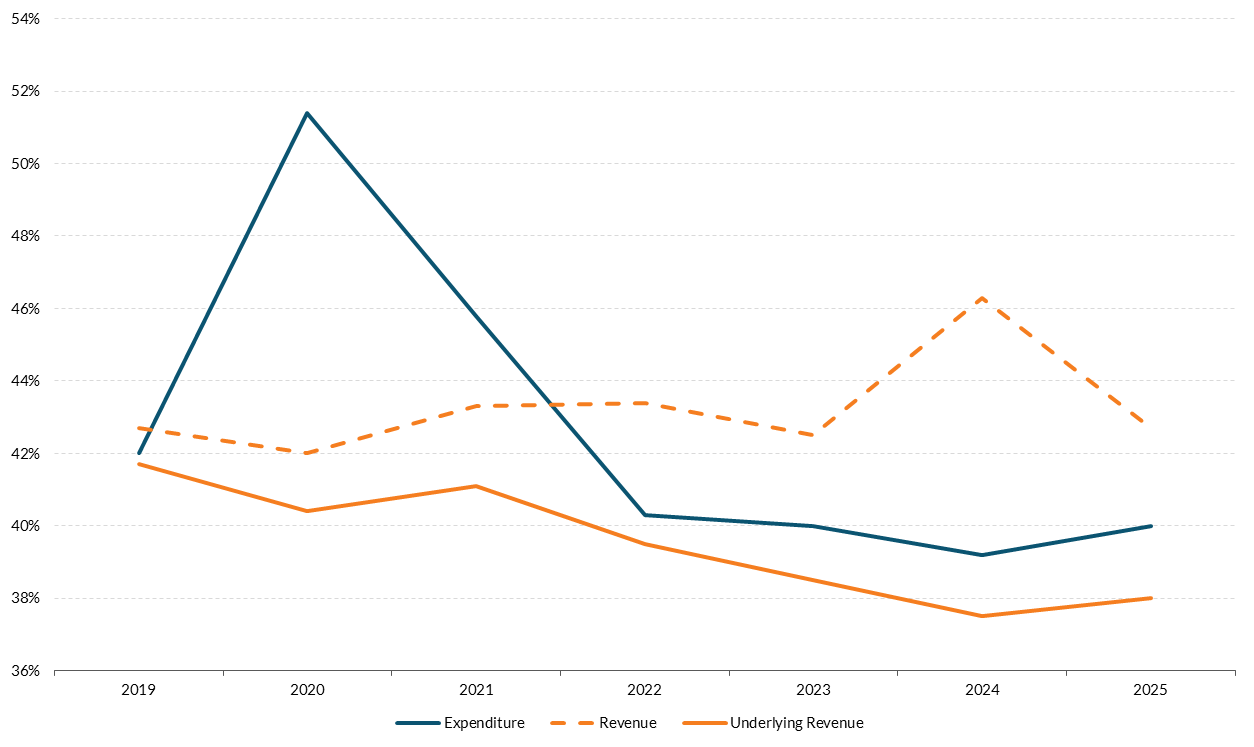

An important element of prudent macroeconomic management is for fiscal policy to have a sustainable medium-term orientation, anchoring expenditure growth to the economy’s sustainable revenue-raising ability, reducing the underlying general government deficit (excluding excess corporation tax), and improving the stability of the tax base by broadening it and reducing concentration risk. Moving fiscal policy to a more balanced stance by purposefully reducing the underlying general government deficit, alongside structural reforms and productivity supports, will avoid unnecessarily adding to aggregate demand. Public spending has risen strongly in nominal and per‑capita terms in recent years, reflecting both needed infrastructure investment and higher current spending (Box C). These demands on the public finances will intensify. To underpin credibility and ensure sound public finances over the medium-term, it is important that a sustainable path for net spending growth is set out and adhered to. At the same time, risks from an excessively narrow tax base have become more acute, given reliance on corporation tax receipts from a small number of MNEs. The Future Ireland Fund and the Infrastructure, Climate and Nature Fund only partly address the additional spending pressures expected in the 2030s and beyond. Growth in recurring government spending must be better managed to avoid repeated upward revisions and overruns and matched by a more sustainable revenue base. Options exist to maintain and widen the tax base, including reform of tax reliefs, property and consumption taxes, and social insurance contributions. Broadening the tax base is also necessary to build the economic space for the required increase in public and private capital investment, as well as to fund the anticipated rise in the cost of maintaining existing public services over the longer-term.

Outlook for the Irish Economy

Recent Developments and Forecast Summary

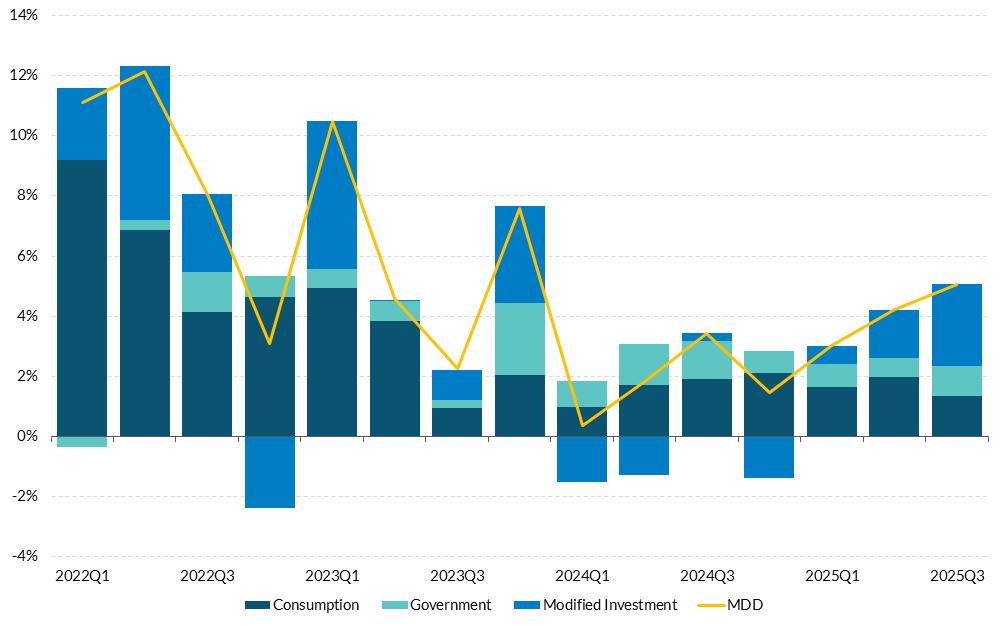

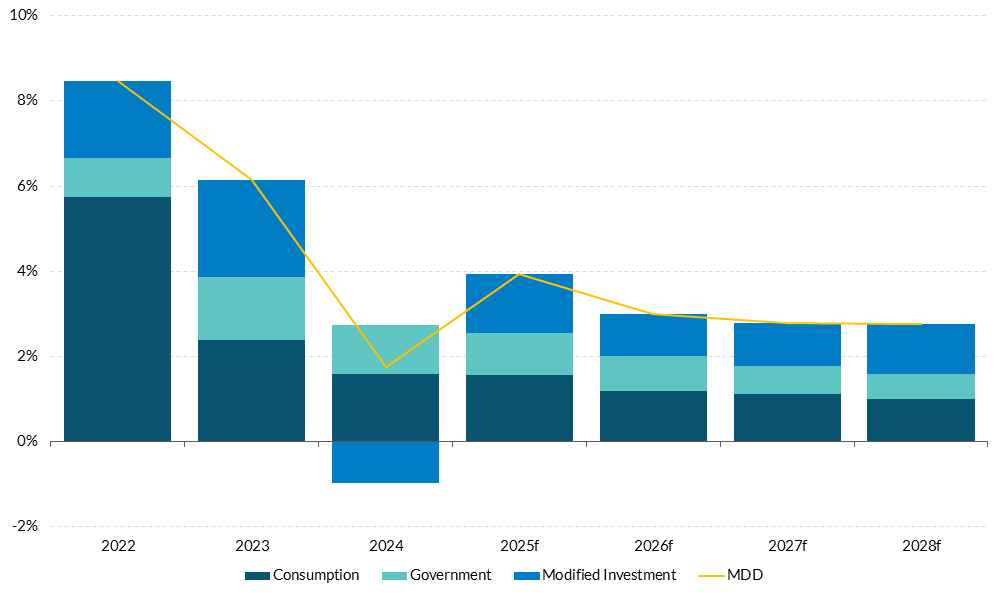

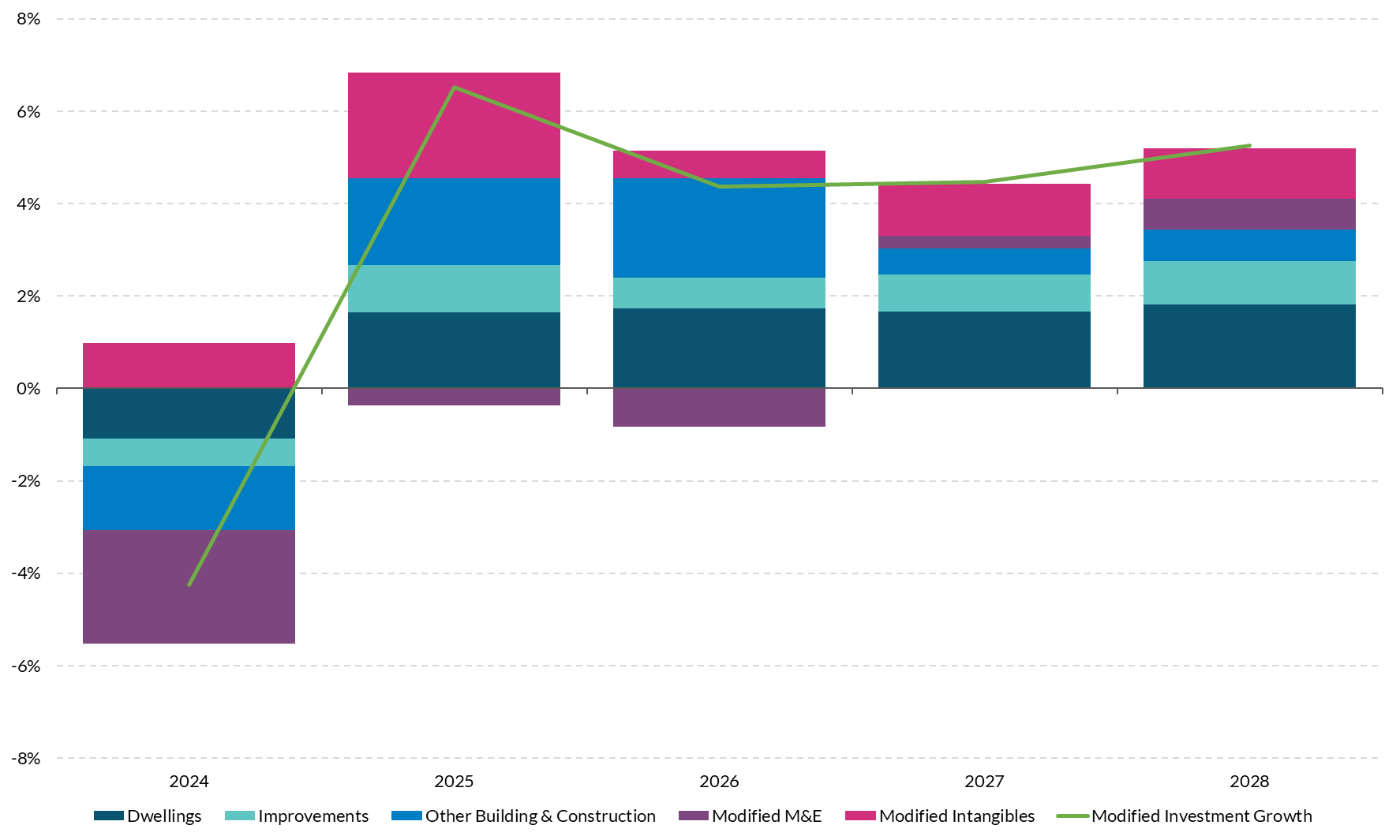

Growth in Modified Domestic Demand (MDD) accelerated up to the third quarter of 2025, driven in large part by a spike in intangible investment by multinational firms in Ireland. Quarterly National Accounts data show that economic activity as measured by modified domestic demand grew by 5.1 per cent in the third quarter compared to the same quarter in 2024 (Figure 1). Growth was driven by an enormous rise in investment in modified intangibles of 42 per cent compared with the same quarter in 2024 which could potentially be once-off in nature. Modified intangibles includes expenditure by firms on software and research and development which is dominated by multinational firms. A jump in investment in “other transport equipment” – mostly airplanes – also boosted MDD in the quarter. In contrast, consumption – which accounts for just under 60 per cent of MDD – was broadly unchanged compared to Q2 2025 and increased by 2.4 per cent compared with Q3 2024. Taking the first three quarters of 2025 and comparing it to the same period in 2024, overall MDD grew by 4.1 per cent. This marked a faster pace of growth in MDD than was observed over the first half of the year, mostly accounted for by the unusually large jump in intangibles investment.

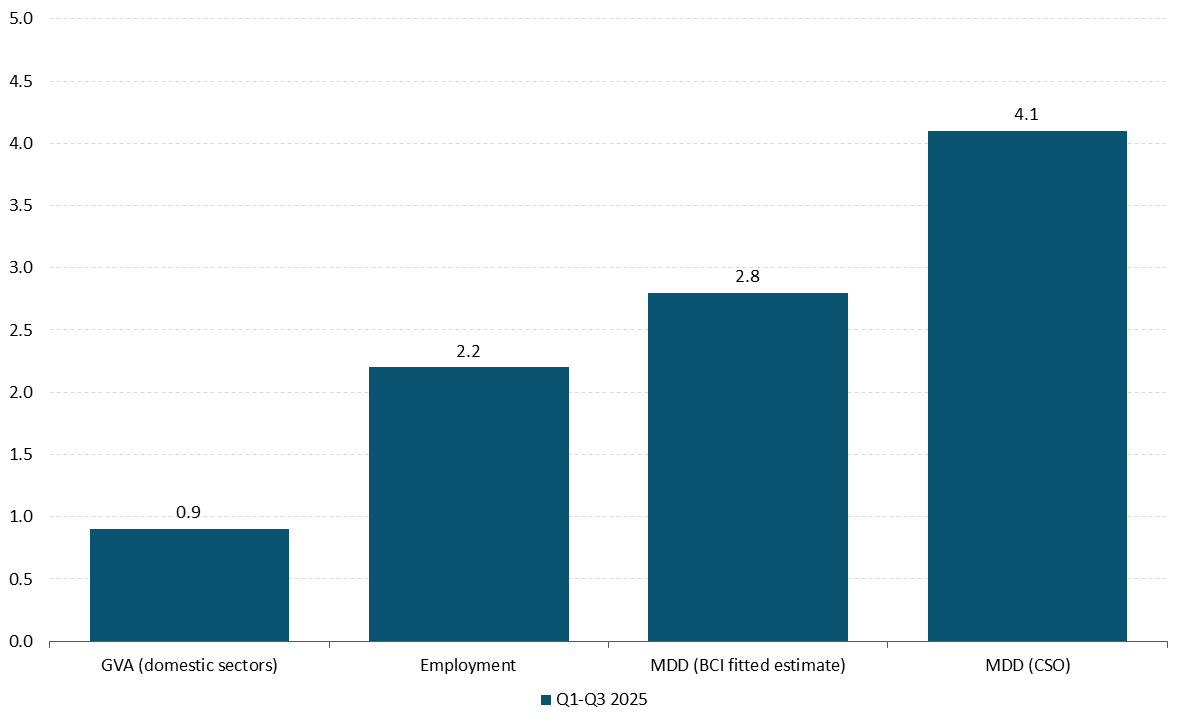

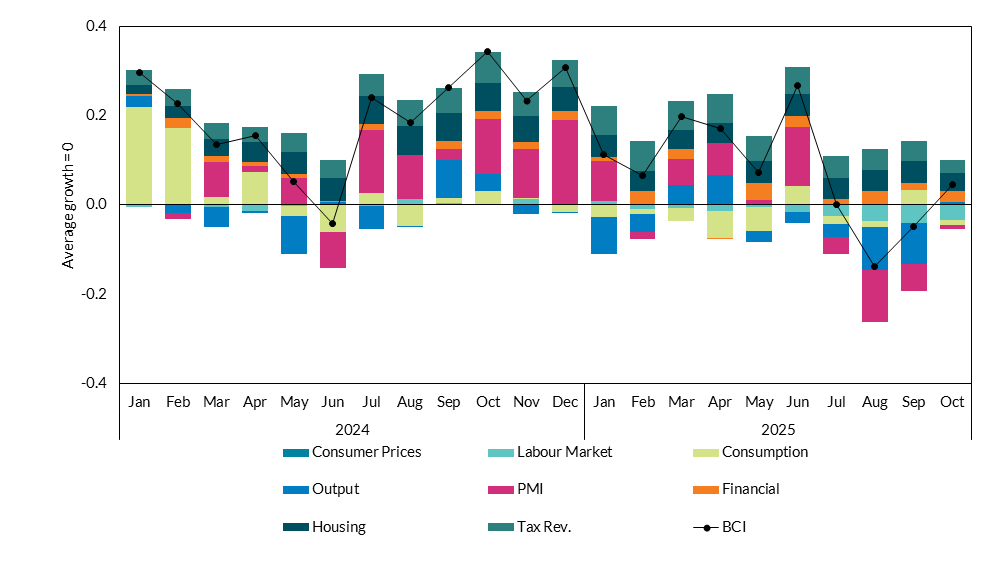

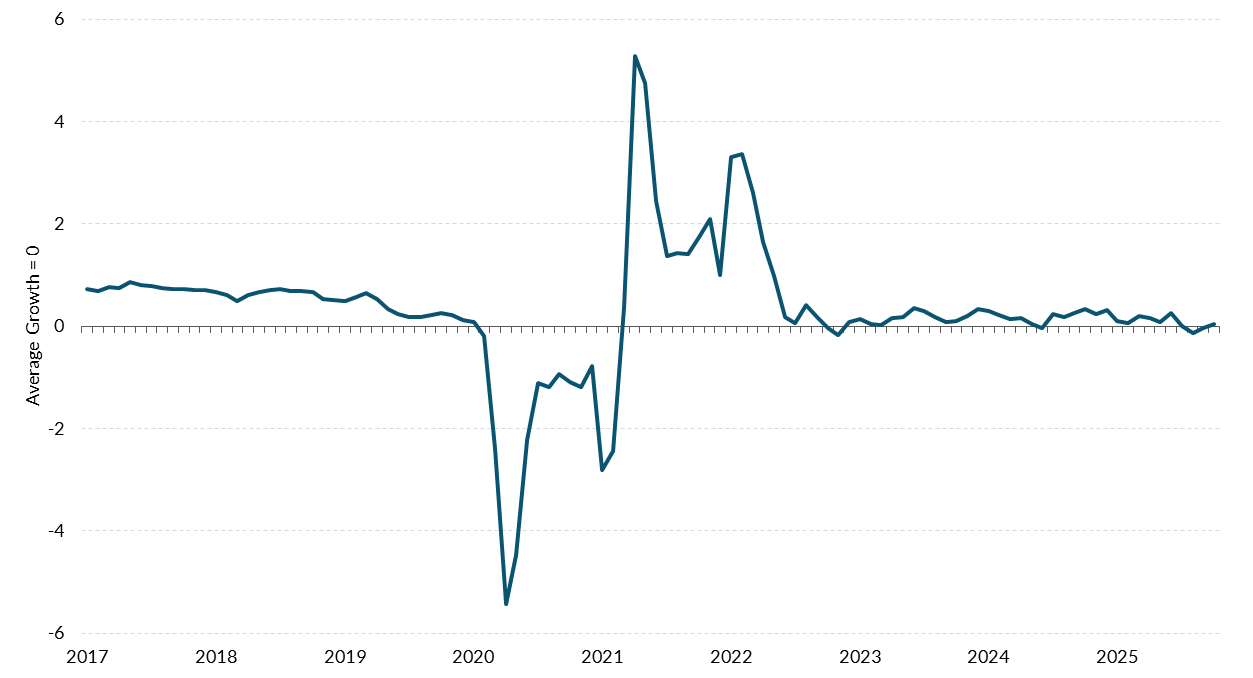

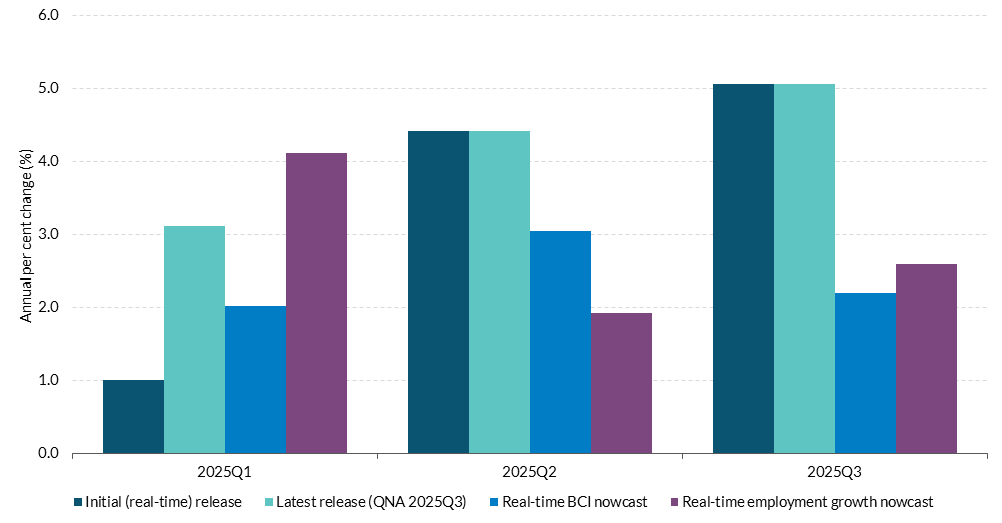

The outturn for MDD in the first three quarters of 2025 is at the upper end of estimates of domestic growth available from a range of other indicators. At 4.1 per cent, the growth in MDD is well ahead of the pace of expansion signified in other indicators (Figure 2). Output (Gross Value Added, GVA) in the domestically-oriented sectors of the economy expanded by just under 1 per cent over the first three quarters. Employment increased by 2.2 per cent over the same period and the pace of employment growth appears to have slowed during the year. The annual growth in employment stood at 1.1 in Q3, whereas the equivalent figure in Q1 2025 was 3.3 per cent. The Central Bank’s Business Cycle Indicator (BCI) summarises the information from the latest high-frequency monthly data, separating out the underlying trend in activity from movements due to noise. The most recent data show that activity has been slightly weaker over the past three months compared to the first half of the year (Figure 3). The main negative contributions to the BCI up to October have been traditional sector output, PMIs (in particular for construction) and weaker labour market data. The BCI can be used to produce a nowcast of MDD and this nowcast estimate is found to provide useful information for interpreting the official provisional estimates of MDD (see Box A). Based on the BCI, MDD growth for the first three quarters of 2025 would have been estimated at 2.8 per cent. Similar to the outturns for employment and the output of the domestically-relevant sectors of the economy, this estimate is also lower than the observed MDD outturn of 4.1 per cent. The reason for the divergence between the different measures of growth over the first nine months of 2025 reflects at least in part the specific factors behind the growth in MDD in the official data, namely the large increases in investment in modified intangibles and airplanes in Q3. MDD is a useful measure that excludes certain components of demand related to the global activities of MNEs and that have a minimal connection to the domestic economy. Nevertheless, changes in other components of investment that are included in MDD – and based on the decisions of a small number of large firms – can still result in overall MDD diverging from other measures of domestic activity such as employment in a given quarter.

Pace of MDD growth accelerated in Q3 2025 driven by modified investment

Figure 1: Contributions to year-on-year change in Modified Domestic Demand (MDD)

Source: CSO. Chart data in accessible format. (XLSX 145.89KB)

MDD outturn up to Q3 2025 is at the upper end of estimates of domestic activity from other indicators

Figure 2: Estimates of growth in domestic activity, Q1-Q3 2025 compared to same period in 2024, % change

Source: CSO and Central Bank of Ireland. Chart data in accessible format. (XLSX 145.89KB)

The BCI weakened somewhat in Q3 2025

Figure 3: Business Cycle Indicator and Contributions, Average growth = 0

Source: Central Bank of Ireland. Chart data in accessible format. (XLSX 145.89KB)

Note: Details on the methodology underpinning the BCI available here (PDF 790.91KB). The zero axis corresponds to the long-run average historical growth rate in realised MDD. Deviations above or below zero therefore signify that activity is growing faster/slower than its historical average rate.

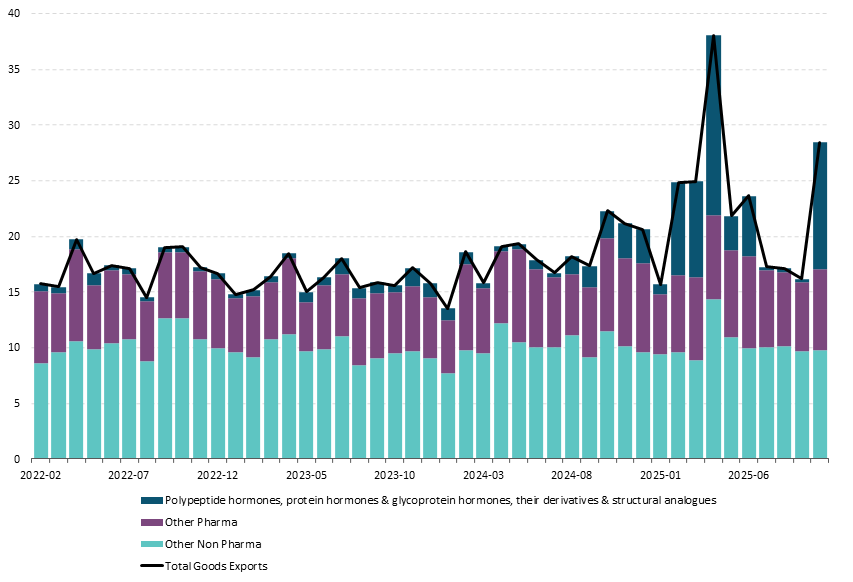

A large increase in pharmaceutical exports has contributed to double-digit GDP growth in the first three quarters of 2025. The pace of growth in pharmaceutical exports eased in Q2 following the exceptional Q1 outturn, which was influenced by a frontloading of exports to the US. However, a combination of the growth in non-pharma goods exports and a renewed resurgence in pharmaceutical exports in September means that overall exports, and hence GDP, will increase sharply in 2025. In the first nine months of the year, these increased by 11.8 per cent and 15.8 per cent respectively.

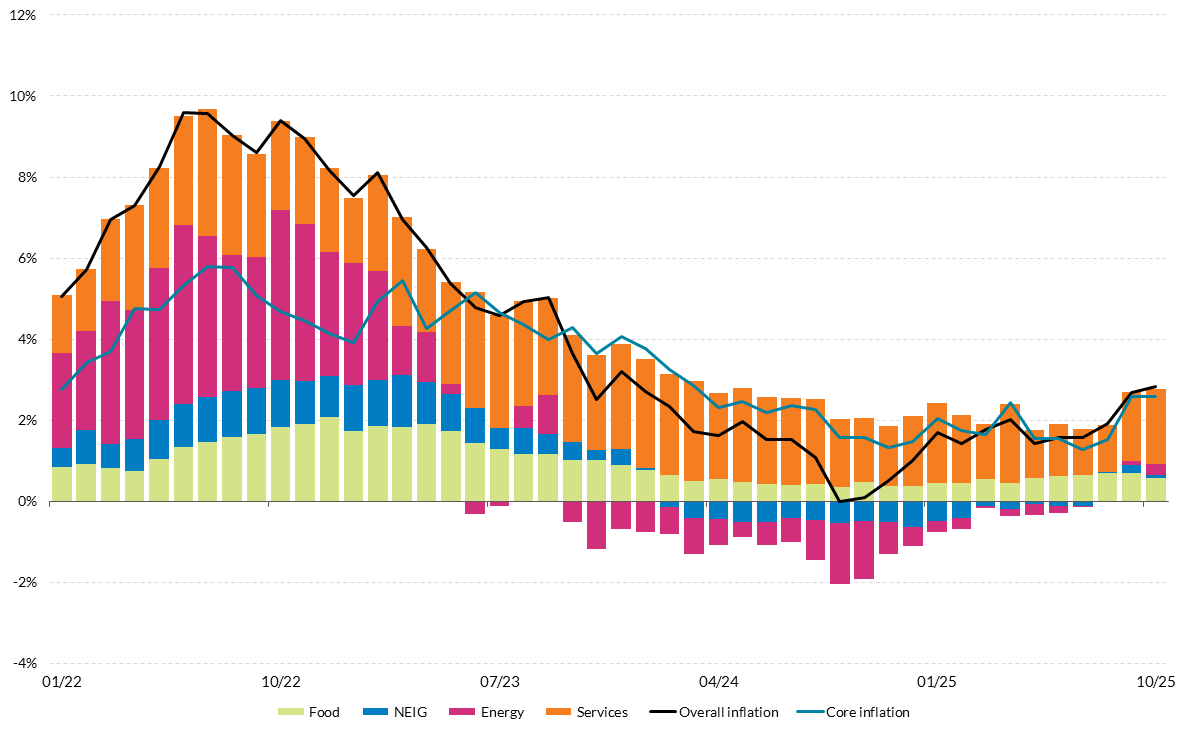

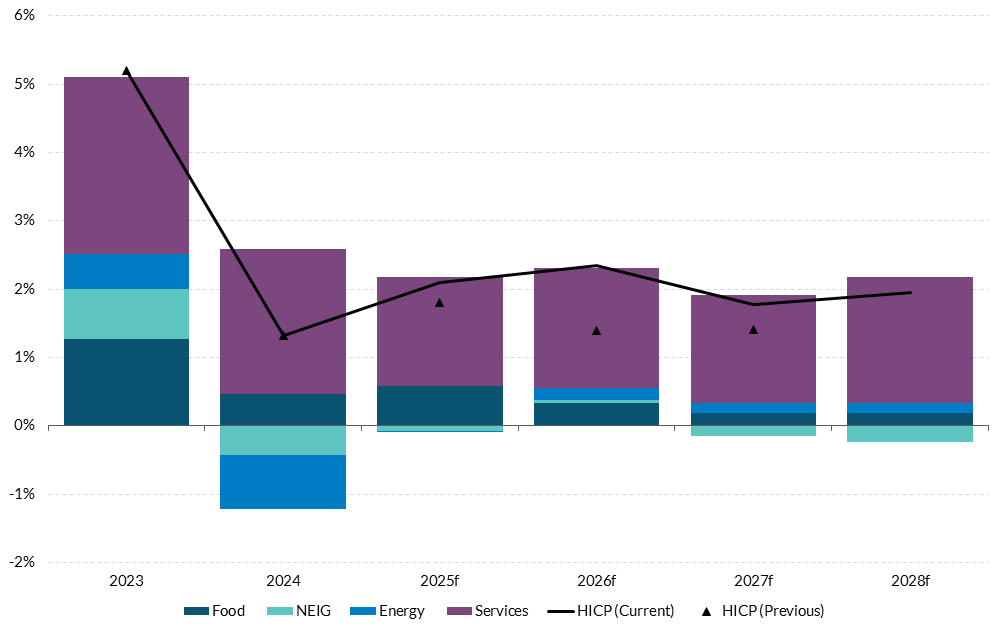

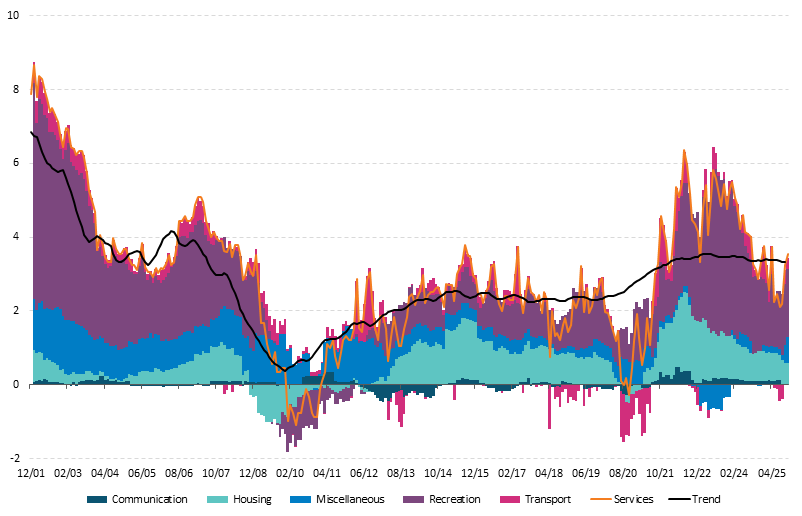

Headline and core inflation have increased in recent months with services making the largest contribution. Inflation has picked up since the publication of Quarterly Bulletin 3 (QB3) in September. Headline HICP increased, on a year-on-year basis, to 3.1 per cent in November, with core inflation rising to 2.6 per cent in October (Figure 4). The equivalent outturns for August were 1.9 per cent and 1.5 per cent. The recent increase in inflation is largely explained by a pick-up in services inflation. This had moderated over the summer, reflecting specifically a decline in the prices of airfares and package holidays, but these effects have reversed since September. Underlying inflation measures have also edged upwards, with all indicators above the 2 per cent threshold and pre-pandemic levels.

Headline inflation has risen with an uptick in services prices

Figure 4: Contributions to headline inflation (year-on-year per cent change)

Source: CSO and Central Bank of Ireland. Chart data in accessible format. (XLSX 145.89KB)

The growth forecast for 2025 has been revised upwards, but the economy is expected to shift onto a slower growth path thereafter. The economy (as measured by MDD) has performed better than expected in 2025 in the face of significant headwinds. Taking account of the realised performance in the year to date along with the stimulus from additional Government expenditure for 2025 announced subsequent to the Budget, overall MDD is projected to grow by just below 4 per cent in 2025. From 2026 to 2028, MDD is forecast to grow at an annual average rate of 2.9 per cent per annum (Figure 5). This marks an upward revision to the projections for 2026 and 2027 from QB3. The improved outlook compared with QB3 is largely due to an upward revision to the forecast for modified investment. This is informed by the resilient outturn for investment in the year to date, a smaller than previously estimated drag on investment from uncertainty over the forecast horizon as well as Government policy decisions that are assumed to support higher investment, especially towards the end of the forecast horizon. Despite the improvement to the outlook compared with the forecasts in September, the projections envisage a slowdown in MDD growth from the 6.1 per cent annual average realised outturn from 2021 to 2024. The projected slowdown in growth is informed by a number of considerations. The rapid growth in employment and incomes that underpinned consumer spending since 2021 is expected to continue to moderate, feeding into a lower projected pace of growth in MDD. Despite the expectation of a pickup in construction activity, growth in overall modified investment is forecast to be modest out to 2028. This is based on the expectation that non-housing investment – in particular investment in machinery and equipment by multinational firms – will be subdued over this period as the more unfavourable and volatile external environment prompts caution on large-scale new investments by MNEs. Headline inflation has been revised up since Quarterly Bulletin 3 but is expected to average 2 per cent out to 2028. Services is projected to be the primary source of inflationary pressures over the forecast period (Figure 6).

Exports are projected to contribute positively to growth over the forecast horizon. On the external side of the economy, the composition of Irish exports – in particular, its concentration in the production of goods and services that are experiencing relatively favourable global demand – means that the central outlook for exports and the MNE-dominated traded sector is positive despite higher tariffs arising. Net exports of goods and services produced in Ireland is forecast to make a positive contribution to growth out to 2028. Combined with the outlook for domestic demand, this underpins the forecast for continued growth in real modified national income (GNI*) which is forecast to average 3.3 per cent per annum on average from 2025 to 2028, slightly above the expected growth in MDD.

Risks to the growth outlook are tilted to the downside. There are a number of risks which, if they materialise, could shift the economy onto a lower growth path relative to the central forecast. As a small open economy with extensive trade and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) linkages with the US the Irish economy, public finances and labour market are exposed to changes in US economic policy and any broader deterioration in the global trading environment. Moreover, Irish exports are highly concentrated in a small number of specific goods and services such that a downturn affecting an individual sector or large firm would lower aggregate exports, with related negative effects on investment, employment, incomes and tax revenue also then arising. Domestically, shortages of key infrastructure are limiting the capacity of the economy to grow at present. Contingent on avoiding any further significant external shocks, there is a risk that capacity constraints could become worse if progress on alleviating infrastructure gaps is inadequate. Over the short run, this could result in higher and more persistent inflation with weaker economic growth occurring over the longer term. Domestic capacity constraints and inflationary pressures – and the associated negative implications for long-term growth – would be aggravated if the pattern of procyclical budgetary policy persists. The latter also poses risks to the long-term sustainability of the public finances.

Table 1: QB4 December 2025 Forecast Summary and Revisions from September 2025 Baseline Projections

| | 2024 | 2025f | 2026f | 2027f | 2028f |

|---|

Constant Prices | | | | | |

| Modified Domestic Demand | 1.8 | 3.9 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 2.8 |

| Modified Gross National Income (GNI*) | 4.8 | 4.8 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 2.9 |

| Gross Domestic Product | 2.6 | 12.8 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 3.3 |

| Total Employment | 2.7 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.7 |

| Unemployment Rate | 4.3 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) | 1.3 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 1.8 | 1.9 |

| HICP Excluding Food and Energy (Core HICP) | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 1.9 | 2.1 |

Revisions from previous Quarterly Bulletin, p.p. | | | | | |

| Modified Domestic Demand | 0.0 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.4 | - |

| Gross Domestic Product | 0.0 | 2.7 | -0.7 | -0.8 | - |

| HICP | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.4 | - |

| Core HICP | 0.0 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.5 | - |

MDD growth expected to slow gradually over the forecast horizon

Figure 5: Contributions to annual change in MDD

Source: CSO, Author’s Calculations. Chart data in accessible format. (XLSX 145.89KB)

Headline inflation is projected to average 2 per cent out to 2028, with services the primary source of upward pressure

Figure 6: Contributions to annual change in headline inflation (%)

Source: CSO and Central Bank of Ireland. Chart data in accessible format. (XLSX 145.89KB)

Forecast Detail

External Environment

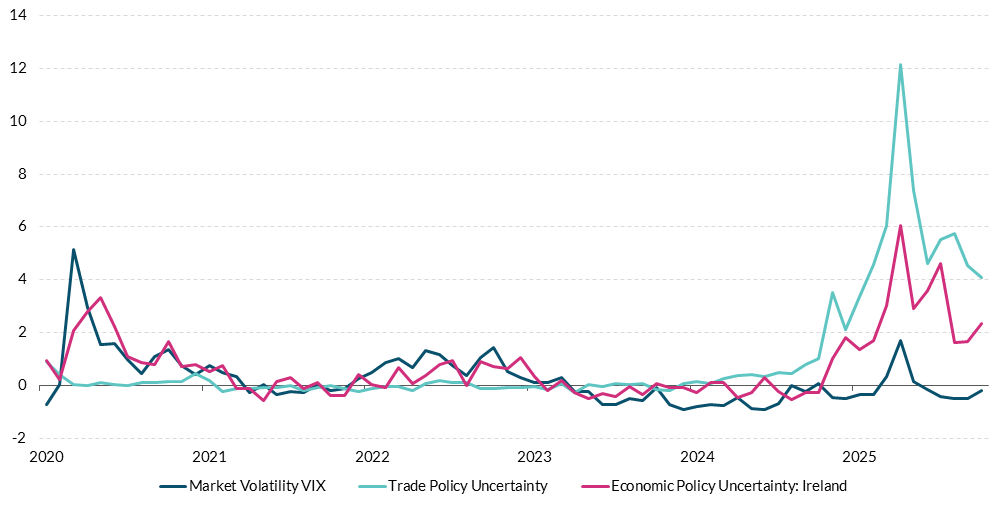

The global economy continues to be characterised by geopolitical developments and an uncertain policy outlook. While trade tensions and related uncertainty have moderated significantly compared to earlier in the year, they continue to shape the trajectory of global trade and activity (Figure 7). In particular, the effects of import tariffs in the US, although more slowly than originally anticipated, are rippling through the global economy, both via US demand for imported goods, but also through secondary effects such as a redirection of trade from China towards different trading partners. Geopolitical tensions and global policy uncertainty remain key contributors to an erosion of business and consumer confidence in a large number of advanced and developing economies. World GDP growth, while remaining relatively robust, is expected to continue slowing down, while global inflation keeps moderating. With Governments in different parts of the world facing similar issues of weak demand, changing economic models, and ageing populations, the sustainability of fiscal policy appears to be increasingly stretched in a number of jurisdictions.

Within this context, the world economy has been more resilient than expected this year, but future prospects are weak and risks tilted to the downside. In the US, capital investment largely fuelled by AI optimism is counteracting cost of living-related consumer pessimism, and a rising unemployment rate. The weakening labour market, combined with inflation that remains above the 2 per cent target (3 per cent in September), are the factors being balanced by US monetary policy makers in the context of the Federal Reserve’s dual mandate. Despite a considerable slowdown compared to 2024, growth in the US economy thus remains strong at a forecasted 2 per cent this year, but partly reliant on continued strength in the technology sector and the stock market. Growth in China slowed to an annual rate of 4.8 per cent in Q3 2025, in line with expectations, and it is forecast to continue weakening in the next years. While goods exports have shown resilience in the face of trade tensions, domestic demand in China continues to be restrained despite Government stimulus.

The December Eurosystem staff

macroeconomic projections for the euro area expect GDP growth of 1.4 this year

and 1.2 per cent, 1.4 per cent and 1.4 per cent in 2026, 2027 and 2028,

respectively. The

projection for 2025 was revised upwards by 0.5 percentage points compared with

the June forecast reflecting better than expected incoming data and a

carry-over effect from revisions to historical data. Stronger foreign demand and lower energy

commodity prices resulted in a 0.1 percentage point upward revision for both 2026

and 2027, compared to June. Over the medium term, euro area economic

growth is expected to be supported by rising disposable income, reduced uncertainty,

stronger foreign demand and fiscal stimulus related to defence and

infrastructure. Euro area headline

inflation is expected to stabilise around the medium-term target of 2 per cent,

with projections for HICP inflation of 1.9 per cent and 1.8 per cent in 2026

and 2027 respectively. Overall weighted external demand for Irish exports is

projected to grow at an annual average rate of 2.3 per cent per annum from 2026

to 2028 (Table 2).

Uncertainty has declined from its spike in April 2025 but remains above historical norms

Figure 7: Standardised measures of uncertainty (number of standard deviations)

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED), Rice, J. (2023), Caldara et al. (2019) and Central Bank of Ireland calculations. Chart data in accessible format. (XLSX 145.89KB)

Table 2: International Economic Outlook

| | 2024 | 2025f | 2026f | 2027f | 2028f |

|---|

| World | 3.3 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.2 |

| Euro area (December 2025 BMPE) | 0.9 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| US | 2.8 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.1 |

| UK | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.4 |

| Japan | 0.1 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| China | 5.0 | 4.8 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 4.0 |

| Emerging economies | 4.3 | 4.2 | 4.0 | 4.2 | 4.1 |

| Weighted global demand for Irish exports | 2.3 | 3.2 | 1.3 | 2.7 | 2.8 |

Notes: Table shows projections for annual GDP growth for major global economies. Forecasts for the euro area and for weighted global demand for Irish exports are from the Eurosystem Staff Macroeconomic Projections, December 2025. Forecasts for the remainder are from the October 2025 IMF WEO.

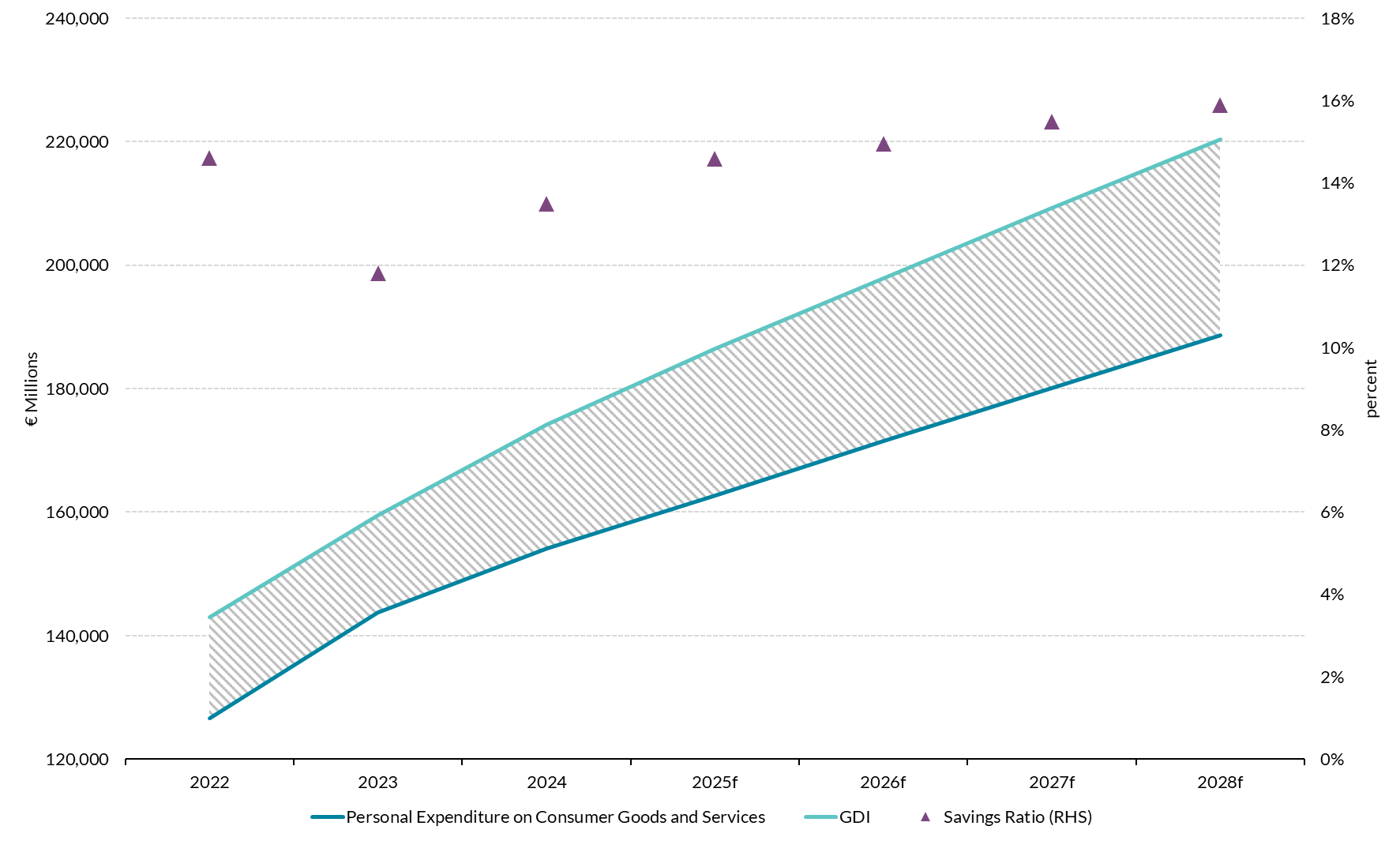

Economic Activity

Consumption is expected to grow by 2.9 per cent in 2025 – a similar rate of growth as in 2024 – but a slowdown in spending growth is projected over the remainder of the forecast horizon as employment and incomes expand at a more modest pace. Despite clear headwinds in the form of higher uncertainty and weaker sentiment, consumer spending has increased at a steady pace throughout 2025 and is projected to grow by 2.9 per cent for the year as a whole. This would bring the level of consumption to 20 per cent above its 2019 level in real terms. The pace of growth of consumption is projected to slow to 2.2 per cent in 2026 and to an annual average rate of 2 per cent in 2027 and 2028. These projections are based on the expectation of more modest increases in employment and incomes from 2026 to 2028, compared to recent outturns. Structural factors including an ageing population and increased propensity to save for housing among younger cohorts, alongside higher levels of uncertainty and precautionary savings motives have supported a gradual upward drift in the household savings ratio over recent years (Boyd, Byrne and McIndoe Calder, 2025) (PDF 1.05MB) and this trend is forecast to continue. By 2028, the household savings rate is forecast to stand at 15.9 per cent, 3.7 percentage points above its long-run (1995 to 2024) average (Figure 8).

Consumption has grown more strongly in 2025 than was expected at the beginning of the year. In March 2025, consumption growth was projected to slow from the 3 per cent outturn in 2024 to closer to 2.6 per cent in 2025 weighed down, in particular, by uncertainty which spiked in Q1 2025. Consumption has outperformed relative to this earlier projection, with average growth of 2.9 per cent from Q1 to Q3 2025 compared with the same period in 2024. Were no further growth in consumption to occur in the final quarter, spending would still expand by 2.5 per cent for the year as a whole. Notwithstanding the solid expected outturn for the year, there are signs of a weakening in consumer spending as the year has progressed. High-frequency data from Central Bank Card Payments Statistics point to a slowdown in the pace of spending growth in Q3 2025 to 10.2 per cent in nominal year-on-year terms, down from an average rate of 11.9 per cent in the first half of the year. Exchequer data on VAT is a good indicator of consumer spending. In the three months to end-October 2025, VAT revenue increased by 2.3 per cent compared with the same three months in 2024. The equivalent growth rate for the preceding three-month period (the three months up to end-July 2025) was 3.5 per cent. Survey evidence from the Consumer Expectations Survey shows a rise in the proportion of households that view themselves as liquidity-constrained to 28.3 per cent in Q3 2025, up from an average of 25.6 per cent in H1 2025. Taken together, these hard and soft data are consistent with a slowdown in consumer spending in the second half of 2025.

Consumption growth projected to slow with a gradual rise in the savings rate

Figure 8: Consumption, disposable income and the savings rate (per cent)

Source: CSO and Central Bank of Ireland. Chart data in accessible format. (XLSX 145.89KB)

Overall modified investment is projected to grow out to 2028 but the outlook is mixed with some multinational-dependent activity expected to stay subdued. Consistent with the performance of household spending, investment spending has proven resilient in 2025, prompting an upward revision to the forecast for 2025 to 6.5 per cent (Figure 9). The improved 2025 forecast is based on the solid realised performance across most of the main components of modified investment in the year to date. The outlook for modified investment beyond 2025 is mixed and subject to a high level of uncertainty. Current central projections are for a rise in modified investment of 4.7 per cent per annum from 2026 to 2028 but with a varied performance expected across individual components. Construction-related activity is expected to continue to grow out to 2028 supported by a gradual increase in housing output. Machinery and equipment investment (dominated by multinational firms) is forecast to contract in 2025 and 2026 and then to grow modestly in 2027 and 2028.

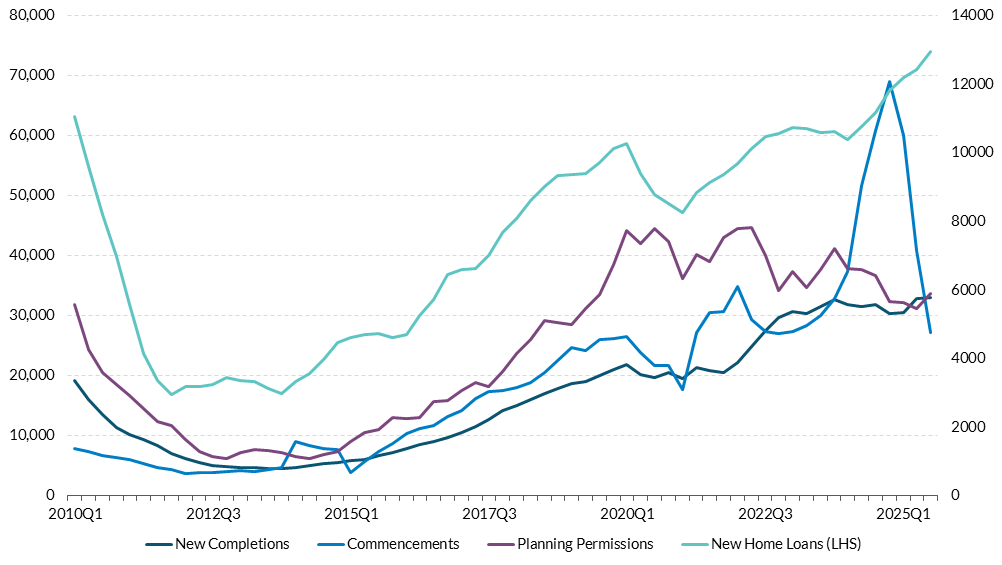

Housing output is projected to rise conditional on progress being made to deliver necessary enabling infrastructure. New dwellings completions came in at 24,387 units in the first three quarters of 2025, 12.6 per cent above 2024 and also slightly above expectations. This has prompted a small upward revision to completions for 2025 to 33,500 units. Commencements amounted to just 10,193 for the same period – down from 52,000 on the first three quarters of 2024 (Figure 10). A decline in commencements in 2025 was expected as the 2024 outturn was boosted by water and energy waivers which expired last year. Historically, housing commencements offered a reliable guide to future completions but this relationship has been disturbed by the policy-induced volatility in commencements over the past eighteen months, introducing greater uncertainty into the forecast for housing completions. To inform the projections for future housing completions, a range of models are used which relate the level of housing completions to indicators such as planning permissions, new home loans, the ratio of house prices to building costs and PMIs. Based on these tools and taking into account other relevant information, housing completions are forecast to reach 37,000, 40,500 and 44,500 in 2026, 2027 and 2028 respectively. Realising this level of housing output is conditional on a number of key assumptions. In particular, the forecasts assume that additional expenditure in the revised National Development Plan (NDP) results in the delivery of new infrastructure that relieves current binding constraints in energy, water and wastewater, thereby providing the necessary infrastructure to enable higher level of housing output. The forecasts also assume that other current bottlenecks around planning and in the availability of zoned land are gradually addressed out to 2028. The revised housing plan (Delivering Homes, Building Communities: An Action Plan on Housing Supply and Targeting Homelessness) contains beneficial elements such as high levels of planned investment in water, energy and transport as well as regulatory reform and changes to zoning. The Accelerating Infrastructure Report and Action Plan contains a series of reforms intended to speed up the delivery of key national infrastructure. If implemented effectively and combined with other announced initiatives such as the proposed changes in building regulations, these reforms should support housing output rising towards the levels envisaged in these projections, if not beyond. Conversely, a failure to make progress on the well-known constraints limiting current housing delivery would result in a lower level of completions than projected in the Bulletin. It is important to note that many of these constraints (in water, energy and transport and in the planning system) are limiting investment spending by businesses in the economy more generally, not only in the housing area.

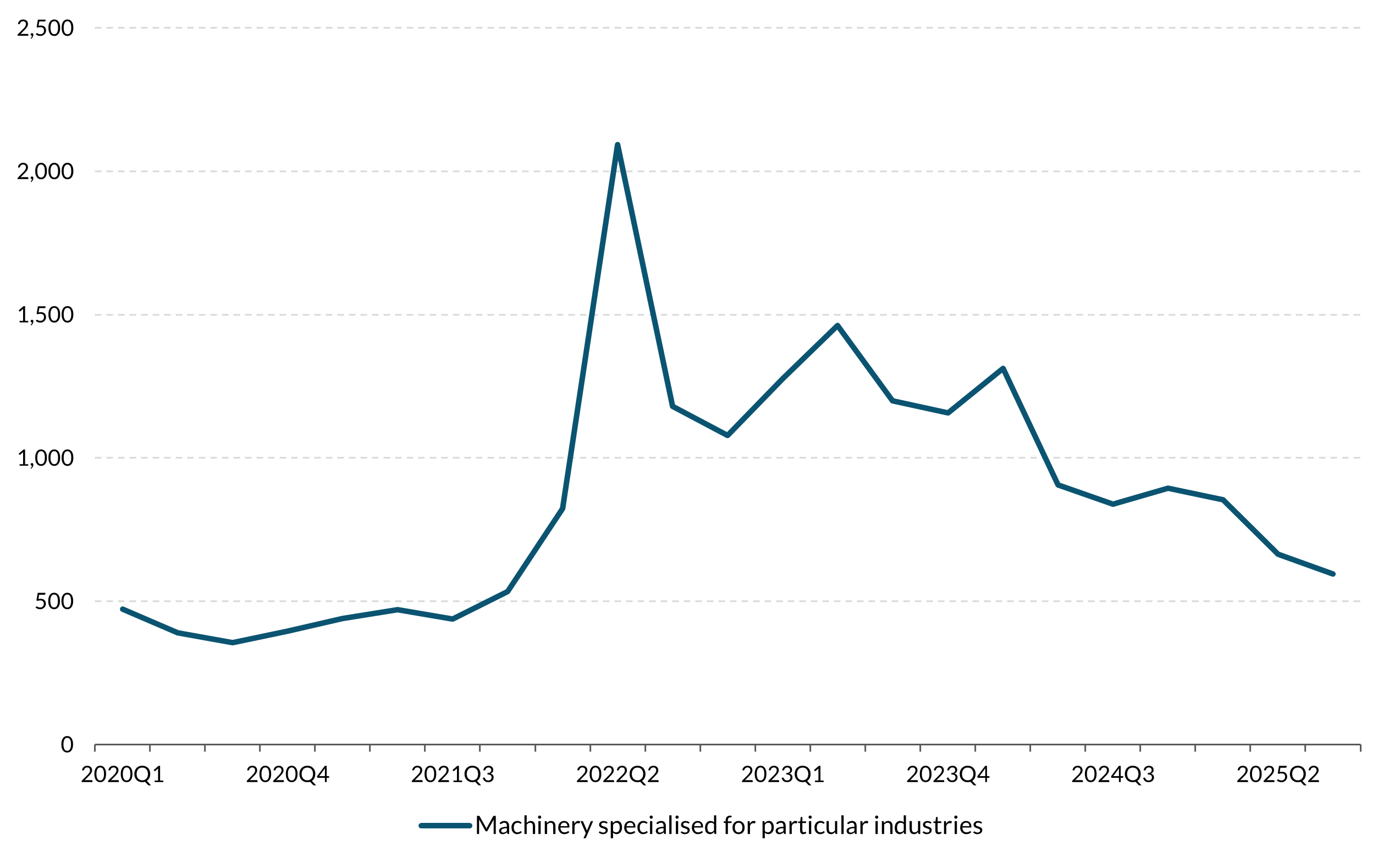

Outside of housing, modified machinery and equipment is expected to remain weak this year and next. Modified machinery and equipment investment represents around one-fifth of overall modified investment and it increased sharply over the period 2021 to 2023. Despite contracting by 10 per cent in 2024, the level of modified machinery and equipment investment last year was still almost 27 per cent per cent above its 2019 level in real terms. This component of investment is dominated by US multinationals and, therefore, its future path will be influenced by the strength of activity in this sector, the performance of large individual firms and the path of overall outward US FDI. Reflecting the expected impact of continued high uncertainty and the effect of tariffs on MNE activity globally, modified machinery and equipment investment is forecast to contract this year and next, before recovering modestly over the remainer of the horizon.

Overall modified investment has increased in 2025 with construction and modified intangible investment expanding but there are signs of weakness in other MNE-dominated parts of activity. The construction PMI is signalling lower activity levels in the second half of the year that could be indicative of weak fourth quarter for building; however, the data are somewhat mixed with the forward-looking element of the construction PMI remaining positive. The services PMI was more overtly positive with both output and futures expectations expanding strongly. The European Commission’s Industry and Services Survey also point to positive expectations for future production or activity for Ireland that should help to support higher investment spending. Other available activity indicators with implications for investment are mixed. Industrial production for the traditional sector was down 3 per cent year-on-year in the third quarter, while activity in the modern sector was up 15.9 per cent. Imports of machinery and equipment increased by 5 per cent year-on-year in Q3 2025. Of particular note is the decline in imports of specialised equipment related to the fit-out of large MNE plants (Figure 12). Lower imports of these goods are likely to reflect reduced investment by multinational firms that may be confirmed in later National Accounts investment data. Using data from Eurostat (available up to 2023), investment by indigenous firms increased up to 2023 but the overall level of investment relative to sales for Irish firms remains low compared to EU peers. Separate data from the CSO Institutional Sector Accounts for 2024 confirm that this pattern continued into last year with the investment rate (investment as a share of gross value added) for domestic non-financial corporations (NFCs) lower than the equivalent rate for foreign-owned NFCs in Ireland and the figure for all euro area NFCs. On credit developments, the pace of growth in net lending by banks to Non-Financial Corporations (NFCs) (excluding financial intermediation) increased on an annual basis up to Q2 2025 but net lending to Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs) remains subdued as repayments have exceeded new lending consistently over recent quarters (Figure 11). Non-bank lenders provide a significant and growing share of credit to SMEs in Ireland. The volume of new lending to SMEs increased by 14 per cent in 2024, from €2.2 billion to €2.5 billion, with the share of non-bank lending to SMEs increasing from 35 per cent in 2023 to 36.5 per cent last year (see Financial Stability Review:II 2025 (PDF 1.41MB)).

Modified investment is forecast to grow as housing activity rises

Figure 9: Contributions to year-on-year change

Source: CSO and Central Bank of Ireland. Chart data in accessible format. (XLSX 145.89KB)

House completions remain below estimated structural demand

Figure 10: Annualised Units

Source: CSO, DoHLGH, BPFI and Central Bank of Ireland. Chart data in accessible format. (XLSX 145.89KB)

Growth in overall bank lending to NFCs has picked up but lending to SMEs remains subdued with high levels of repayments

Figure 11: Annual (%) change in net lending

Source: Central Bank of Ireland. Chart data in accessible format. (XLSX 145.89KB)

Notes: Chart shows the annual rate of change in net lending by banks to NFCs and SMEs, excluding financial intermediation, from Table A14 and Table A14.1 in Central Bank SME and Large Enterprise Credit Statistics.

Imports of specialised machinery and equipment are falling

Figure 12: imports, € million

Source: CSO. Chart data in accessible format. (XLSX 145.89KB)

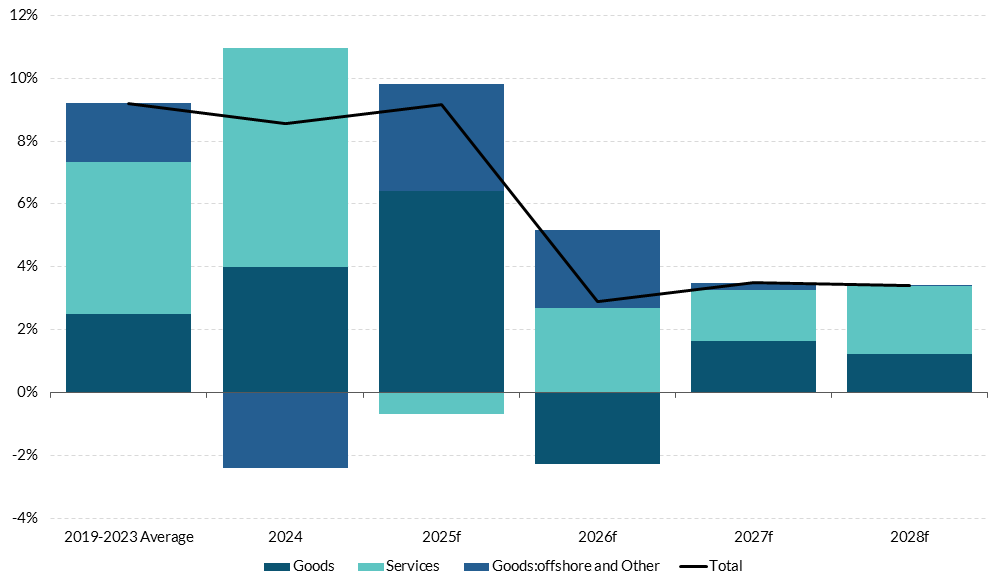

Exports of goods and services are forecast to grow out to 2028, despite subdued global demand. Reflecting the impact of high global tariffs, ongoing trade tensions and levels of uncertainty above recent historical norms, the global economy is projected to grow at a subdued pace out to 2028. Irish exports will not be immune from this weakness in external demand and will grow more slowly than would have occurred in the absence of tariffs (Central Bank of Ireland, 2025 (PDF 1.4MB)). Nevertheless, the specific composition of Irish exports is expected to provide significant mitigation against effects of the general weakness in global trade. Underlying global demand for the main outputs of the pharmaceutical sector (which account for the majority of goods exports) appears strong and should support continued growth in goods exports. Meanwhile, services exports – which are currently not subject to tariffs and have grown by 7.4 per cent on average per annum from 2020 to 2024 – are forecast to expand from 2026. Putting these elements together, overall exports are projected to rise by 3.3 per cent per annum on average in between 2026 and 2028 (Figure 13). Imports are projected to grow by 6.6 per cent in 2025, easing to an average of 2.8 per cent in 2026–28, consistent with the path of final demand.

Goods exports increased sharply in Q1 2025 and have remained at a high level up to Q3. Over the first five months of the year, goods exports to the US surged – increasing by 153 per cent compared to the same period in 2024. This was influenced by firms front loading exports to the US in advance of tariffs but also, as described in previous Bulletins, signs of strong underlying demand for particular pharmaceutical products produced in Ireland. The increase in pharma exports in 2025 has been concentrated in one product category, namely polypeptide hormones (which includes ingredients in drugs to treat diabetes and obesity) (Figure 14). In the first nine months of 2025, 94 per cent of the overall increase in merchandise exports has been accounted for by this single product category. Exports of this product group began to increase sharply from mid-2024 (in advance of front-loading activity) and is driven by a small number of firms, some of which opened new manufacturing capacity in Ireland in recent years. Although pharma exports were weaker from June to August following the exceptional increase in Q1 this year, there was a renewed surge in exports in September attributable to the same polypeptide product category. In September, the value of pharma exports increased by 73 per cent compared with September 2024. Thus, although frontloading produced an exceptional Q1 outturn, stripping out this effect there appears to be strong growth in underlying pharma exports arising from fast growing global demand for weight-loss and diabetes-related medicines and ingredients produced in Ireland. Since September, several large multinational pharmaceutical firms with a substantial manufacturing presence in Ireland, including Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk and Pfizer, concluded agreements with the US administration. While the specific details of the agreements differ for each firm, in the case of all three the agreements involve commitments regarding access to, and pricing, of certain medicines in the US in return for a three-year grace period on the introduction of tariffs. The agreements with these firms and similar deals announced with other firms mean that at least in relation to tariffs, there has been some reduction in uncertainty relative to the position in the first half of 2025.

Non-pharma exports have also risen in 2025 and were up by over 9 per cent in the first nine months of the year compared to the same period in 2024. There was notable growth in exports of office machines and automatic data processing machines (including computers). Services exports declined by 1.7 per cent in the first three quarters compared to the same period in 2024. The decline is largely due to a negative year-on-year outturn for Q2 2025. Partly reflecting a once-off transaction, services exports jumped by over 23 per cent in Q2 2024. As this did not repeat in Q2 2025, exports registered a year-on-year decline of over 10 per cent in the quarter. Services exports increased by just under 2 per cent in real terms in Q3 2025 compared to the same quarter in 2024, with data from the Balance of Payments showing continued strong growth in exports of ICT services.

The modified current account has recorded a large surplus in recent years, largely reflecting a surplus on merchandise and services trade. The merchandise surplus remains large, driven by high-value exports in pharmaceuticals, medical products and other manufactured goods. The services balance is also in large surplus, supported by computer and business services exports. When the income balance is adjusted to take account of depreciation on R&D service imports and trade in IP, aircraft leasing depreciation and redomiciled incomes, the modified current account registered a surplus of over €25 billion in 2024.

The headline current account balance is, however, significantly affected by globalisation-related activities, including the profits of redomiciled PLCs, depreciation on on-shored intellectual property and the operations of aircraft leasing firms. These flows are sizeable but have a limited connection to underlying domestic income. The modified current account (CA*) adjusts for these factors and therefore provides a clearer signal of the external position of the domestic economy. On this modified basis, the current account surplus increased to 8.2 per cent of GNI* (€25 billion) in 2024. The headline current account balance was €91 billion in 2024.

In 2025, the CA* surplus is projected to remain elevated. This is supported by a sharp rise in pharmaceutical exports evident in the first nine months of the year and continued strength in other merchandise exports, together with ongoing growth in services exports. Thereafter, the modified surplus is forecast to narrow somewhat as the positive contribution of net trade gradually declines, although it is expected to remain in surplus over the forecast horizon.

Strong growth in pharmaceutical exports is forecast to drive overall export growth in 2025, with a more balanced contribution from goods and services thereafter

Figure 13: Per cent

Source: CSO and Central Bank of Ireland. Chart data in accessible format. (XLSX 145.89KB)

Large increases in goods exports driven by one product category

Figure 14: monthly value of goods exports by product, € Billions

Source: Eurostat. Chart data in accessible format. (XLSX 145.89KB)

Inflation

The central forecasts for headline inflation have been revised up since the last Bulletin. Headline inflation is now projected to be 2.1 per cent in 2025 (up from 1.8 per cent in QB 3 2025) (Table 3). It is then forecast to rise by 2.3 per cent next year and 1.8 per cent in 2027 (each a higher rate of headline inflation than the last Bulletin) with inflation projected to stand at 1.9 per cent in 2028. The upward revisions mainly reflect recent developments in the services component and moderate increases in energy prices. The forecasts for food price inflation remain broadly unchanged since the last Bulletin. While prices for certain food products have increased of late (see Box A QB3 2025), there is not a broadly-based rise in such prices. Technical assumptions for food commodities point to a moderation in food prices over the forecast horizon, with a stronger euro contributing by easing cost pressures on processed food.

There has been little change to key assumptions underlying the inflation forecasts relative to the last Bulletin in September. Energy price assumptions based on market futures are broadly unchanged, with oil prices assumed to remain below $70 per barrel over the forecast horizon. Gas and electricity prices are expected to rise by 2 per cent and 3 per cent, respectively, in 2025. Subsequently, they are assumed to be marginally lower than 2024 levels and to remain unchanged thereafter. The euro-dollar exchange rate is assumed to exhibit little change, while that of the euro to the GBP is assumed to rise slightly, from 0.87 to 0.88.

Table 3: Inflation Projections

| | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 |

|---|

| HICP | 1.3 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 1.8 | 1.9 |

| Goods | -1.5 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| Energy | -7.8 | -0.2 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Food | 3.0 | 3.7 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Non-Energy Industrial Goods | -1.9 | -0.3 | 0.3 | -0.7 | -1.1 |

| Services | 4.1 | 3.0 | 3.3 | 3.0 | 3.5 |

| HICP ex Energy | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 1.8 | 2.0 |

| HICP ex Food & Energy (Core) | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 1.9 | 2.1 |

Source: CSO, Central Bank of Ireland

Higher inflation has been evident in recent months. Year-on-year headline (HICP) inflation has risen in recent months and stood at 2.8 per cent in October. This pickup largely reflects higher services inflation and base effects. Services inflation moderated over the summer months reflecting a drop in airfare and holiday-package prices that were larger than typical seasonal fluctuations (Figure 4). This influence on inflation has been reversed of late and, while primarily reflecting a base effect from later months of 2024, this has also affected the headline rate. Price developments in tuition fees and certain insurance (health and motor) premia have also exerted upward pressure on services inflation in recent months. While monthly outturns for services inflation have been somewhat volatile, estimated trend services inflation has been broadly flat at around 3.4 per cent throughout 2025 (Figure 15). Recently announced increases in prices by large energy providers are putting upward pressure on headline inflation. Measures of underlying inflation, including HICP excluding Food and Energy inflation, have started to show some upward movement in recent months and are now above 2 per cent (Figure 16).

Moderating airfare and rising education fees drive uptick in services inflation

Figure 15: Contributions to services inflation (year-on-year per cent change)

Source: CSO and Central Bank of Ireland. Chart data in accessible format. (XLSX 145.89KB)

Note: Trend is estimated from an unobserved component model.

Underlying inflation measures have registered a modest increase recently, continuing to hover in the region of 2 per cent

Figure 16: Underlying measures of inflation, year-on-year percentage change

Source: Eurostat, Central Bank of Ireland calculations. Chart data in accessible format. (XLSX 145.89KB)

Note: Chan et al. (2018) is followed here. We use Consensus Economics as the source of inflation expectations for Ireland.

Labour Market and Earnings

Employment growth is projected to slow out to 2028 with a gradual rise in unemployment. The outlook for employment growth remains relatively unchanged from that in the last Bulletin, with a 2.1 per cent increase expected this year, slowing to 1.9 per cent in 2026 and 1.8 per cent in 2027. Looking ahead, a slower rate of job creation is expected to have a stronger negative impact on those attempting to enter the labour market from inactivity – mainly being younger age cohorts. With caution surrounding investment decisions by firms and a slowdown in economic activity expected, a marginal increase in the annual average unemployment rate, up to 5 per cent of the labour force, is expected out to 2028. A long-term risk to the Irish labour market is the interplay of an ageing workforce and the adoption of artificial intelligence (AI). Occupations with higher shares of older workers tend to be those where AI adoption is less likely to occur, meaning that as these workers retire, acute labour shortages may emerge in the absence of sectoral reallocation and retraining programmes or net inward migration meeting labour demand needs (see Box B).

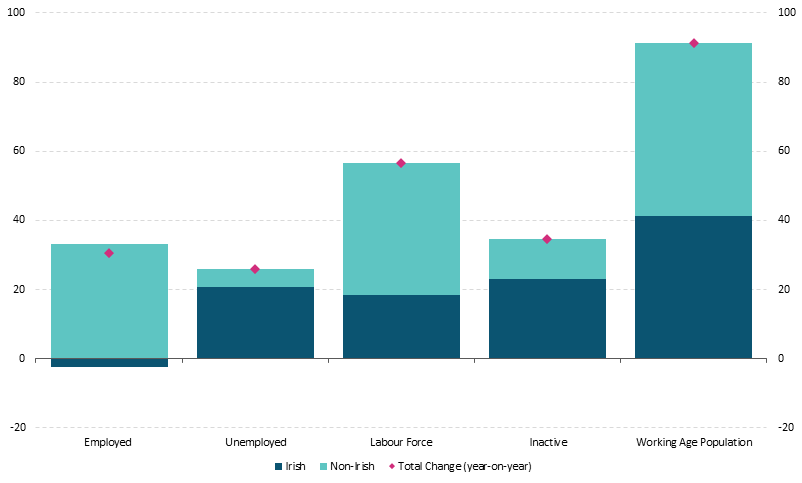

Employment growth slowed in the year to Q3 2025, with declining youth employment offsetting growth in other areas. Following a year-on-year increase of 1.1 per cent (+30,700 persons), the level of employment reached 2,828,500 persons in the third quarter of the year. This was the lowest year-on-year growth rate observed in over four years and is partly reflective of base effects as Q3 2024 was a particularly strong quarter for employment growth. Excluding these base effects, underlying labour demand continues to moderate. The unemployment rate rose to 5.3 per cent in Q3 2025, the highest level in four years. Employment Permit data for January to September point to a 25 per cent decline in inward migration relative to the same period in 2024, which may signal a further slowdown in job growth. The year-on-year increase in employment in Q3 2025 was driven entirely by non-Irish citizens, with employment for Irish citizens remaining broadly flat (Figure 17). The largest sectoral growth in employment was observed in Transport (+15.8 per cent) and Finance (+4.8 per cent), while employment declined in five sectors, including Public Admin (-6.8 per cent) and Accommodation and food services (-4.4 per cent). Employment losses were strongest for the 15 to 24 years age category (-4.8 per cent year-on-year), which likely aligns with the decline in part-time employment (-0.7 per cent). Relative to the 1.1 per cent rise in employment, total hours worked increased year-on-year by 0.6 per cent, implying a further reduction in average hours worked.

Increases in both employment and unemployment contributed strongly to a year-on-year increase in the labour force in Q3 2025

Figure 17: Year-on-year change, 000s persons

Source: CSO,LFS. Chart data in accessible format. (XLSX 145.89KB)

Note: Chart shows the year-on-year change in levels for each ILO status (number of persons) and a breakdown in the change between Irish and non-Irish citizens.

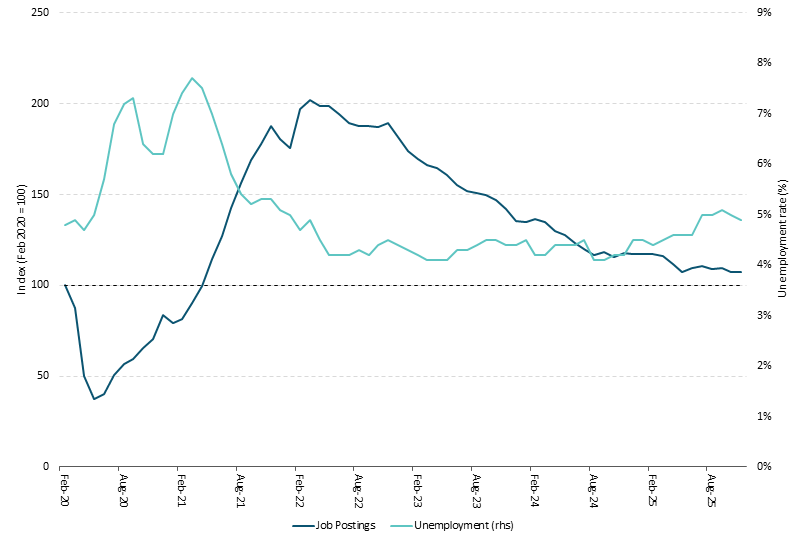

The unemployment rate increased in the third quarter of 2025 with a higher rate now projected out to 2028. Labour demand continues to moderate with Indeed job postings data showing a 7.4 per cent year-on-year decrease in indexed levels for October (Figure 18). The quarterly rate of unemployment rose from 4.8 per cent in Q2 2025 (129,600 persons) to 5.3 per cent (155,400 persons) in Q3, the highest unemployment rate since Q3 2021. There was a broad-based increase in unemployment across all age categories, although over one-third of the aggregate increase in unemployment was attributable to persons aged under 25 years. The annual unemployment rate projection for 2025 has been revised upwards to 4.8 per cent. Wider measures of labour slack, such as the Potential Additional Labour Force, experienced a year-on-year decline in levels of 10,200 persons in Q3. These partly offsetting developments point to unemployment rising, at least in part, due to a movement of persons from inactivity into the labour force. Additional factors which have contributed to unemployment rising alongside employment are cohort effects. This refers to the development whereby there are increasing numbers of 15–24-year-olds entering the working age population, coinciding with a consistent slowdown in the hiring rate (those in employment less than 3 months) since Q1 2022. These factors, when combined, have seen lower transition rates to employment occurring, resulting in an uptick in youth unemployment.

Job postings have declined year-on-year while the unemployment rate has increased

Figure 18: Job postings (index, LHS), Unemployment rate (per cent, RHS)

Source: CSO and Indeed. Chart data in accessible format. (XLSX 145.89KB)

Note: Chart shows the year-on-year change in the indexed level of Indeed job postings on the left-hand axis and the monthly unemployment rate on the right-hand axis.

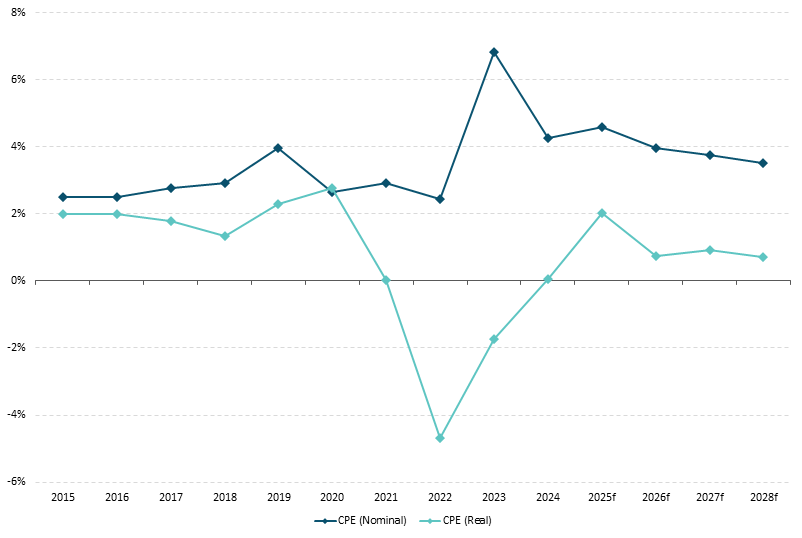

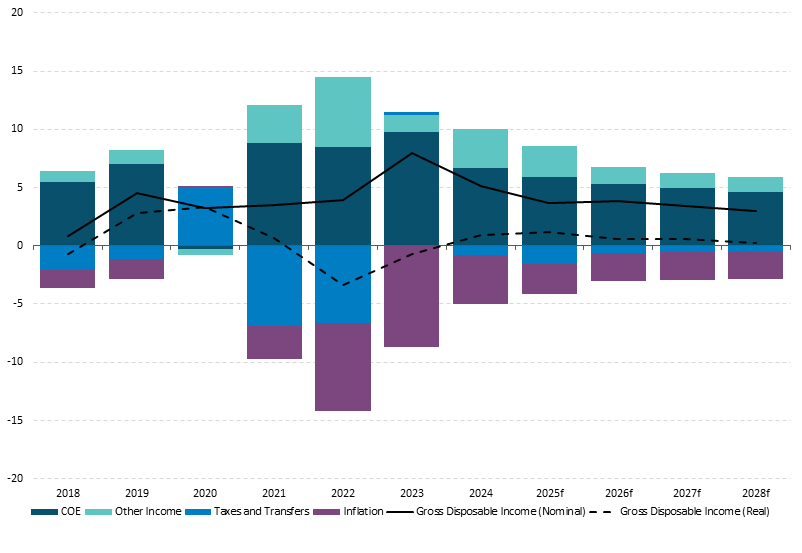

Real compensation per employee is expected to increase over the forecast horizon, supporting further gains in household disposable income. Nominal compensation per employee increased by 6.1 per cent year-on-year in Q3 2025, a faster pace of growth than in previous quarters. This reflected a combination of factors including strong wage growth in sectors such as Professional, Financial and Public sectors. Composition effects also played a role with lower youth and part-time employment increasing average wage levels for remaining workers. The equivalent rise in real CPE in Q3 2025 was 4.1 per cent. Data from Indeed show that growth in nominal posted wages for Ireland has been steady throughout 2025 averaging 4.4 per cent to October, a stronger pace of growth than observed for the euro area. For the full year, compensation per employee is projected to increase by 4.6 per cent in nominal terms and 2 per cent in real terms in 2025. Wage growth is expected to moderate over the forecast horizon due to a combination of weakening labour demand and a gradual increase in the unemployment rate (Figure 19). A minimum wage increase of 4.8 per cent has been approved for January 2026, while the Public Sector Pay Agreement will conclude in June 2026 with two additional 1 per cent increases in nominal pay remaining in the first half of next year. Although Budget 2026 made no adjustments to taxation bands, Gross Disposable Income per household is projected to grow by an annual average of 0.6 per cent in real terms over the forecast horizon to 2028 (Figure 20). A rise in real wage growth should support consumption as well as a projected gradual rise in the savings rate.

Compensation per employee exhibited positive real growth in 2024 with sustained real wage growth projected out to 2028

Figure 19: Year-on-year growth rate (per cent)

Source: CSO and Central Bank of Ireland calculations. Chart data in accessible format. (XLSX 145.89KB)

Note: Chart shows the year-on-year change in real and nominal compensation per employee figures form 2015 onwards. Forecasted levels out to 2028 are included.

Gross Disposable Income per Household is expected to rise out to 2028

Figure 20: Year-on year growth in Gross Disposable Income and underlying components

Source: CSO and Central Bank of Ireland calculations. Chart data in accessible format. (XLSX 145.89KB)

Table 4: Labour Market Forecasts

| | 2024 | 2025f | 2026f | 2027f | 2028f |

|---|

| Employment (000s) | 2,757

| 2,816

| 2,870

| 2,922

| 2,971

|

| % change | 2.7 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.7 |

| Labour Force (000s) | 2,880 | 2,958 | 3,016 | 3,075 | 3,126 |

| % change | 2.7 | 2.7 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.7 |

| Participation Rate (% of Working Age Population) | 65.8 | 66.2 | 66.2 | 66.3 | 66.3 |

| Unemployment (000s) | 123 | 143 | 146 | 153 | 155 |

| Unemployment (% of Labour Force) | 4.3 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

Public Finances

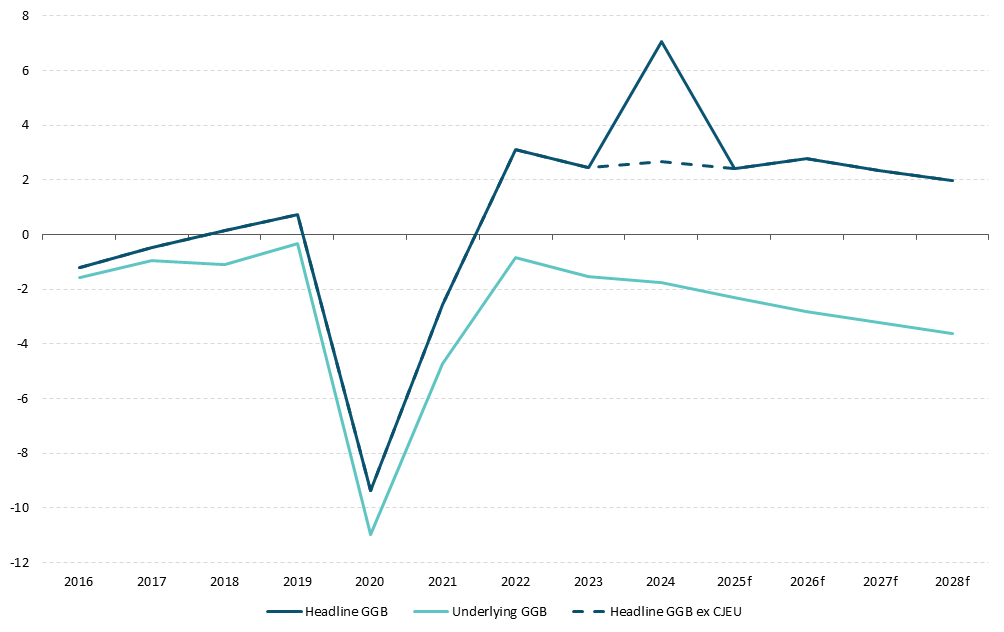

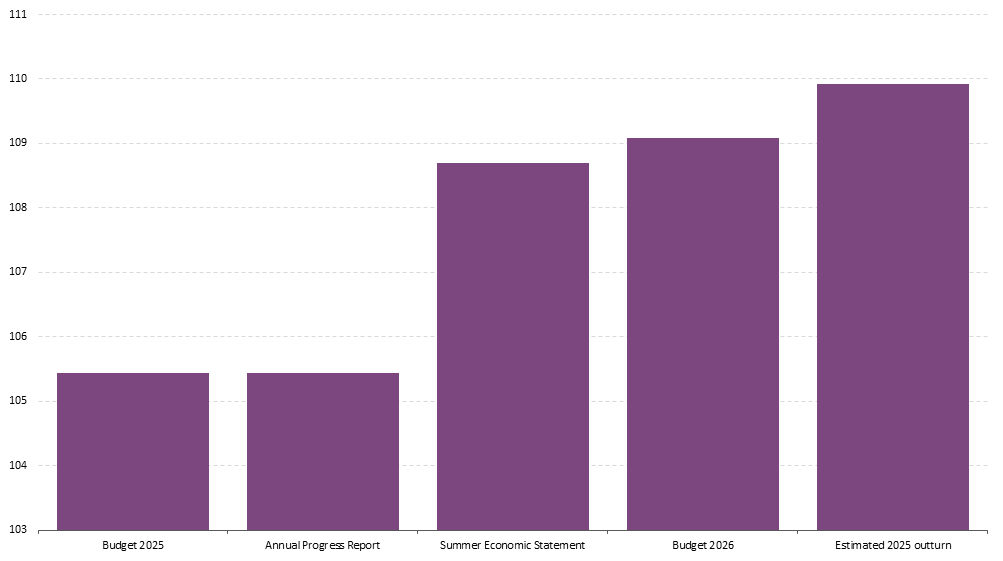

The underlying budget deficit is projected to rise over the forecast horizon as expenditure growth exceeds the increase in revenue, excluding excess corporation tax (CT). Underlying revenue growth (excluding estimated excess corporation tax) is expected to record annual growth of 5.5 per cent on average over the period 2026-2028, while expenditure is forecast to increase by 6.7 per cent. As a result, the underlying budget deficit is projected to deteriorate from -2.3 per cent of GNI* in 2025 to -3.6 per cent in 2028 (Figure 21). The headline general government (GG) surplus is projected to average 2.3 per cent of GNI* from 2026 to 2028, with the implementation of the Minimum Tax Directive next year expected to provide a significant boost to corporation tax (CT) receipts (Table 5). The outlook for both the headline and underlying budget balances are more favourable in this Bulletin compared with the forecast in September as stronger than expected revenue growth outweighs an upward revision to expenditure. The forecast for a persistent underlying budget deficit out to 2028 reflects a combination of factors. Ageing and other stand-still costs are already exerting upward pressure on government spending and this will build over the forecast horizon (Box C). At the same time, revenue growth (excluding excess CT) is forecast to slow in line with the projection for more moderate growth in domestic activity and employment. Lastly, a pattern of repeated upward revisions to government spending has become established (Figure 22). There are significant downside risks to the projections for the public finances, outlined in the Balance of Risks below.

Table 5: Key Fiscal Indicators, 2024-2028

| | 2024 | 2025(f) | 2026(f) | 2027(f) | 2028(f) |

|---|

| GG Balance (€bn) | 22.6 | 8.2 | 9.9 | 8.8 | 7.8 |

| GG Balance (% GNI*) | 7.0 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 2.3 | 2.0 |

| GG Balance (% GDP) | 4.0 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.0 |

| GG Debt (€bn) | 215.4 | 212.9 | 210.4 | 210.4 | 211.8 |

| GG Debt (% GNI*) | 67.1 | 62.3 | 58.6 | 55.5 | 53.0 |

| GG Debt (% GDP) | 38.3 | 31.5 | 29.4 | 27.8 | 26.4 |

| Excess CT (€bn) | 14.1 | 16.1 | 20.0 | 21.0 | 22.3 |

| Underlying GGB (€bn) | -5.7 | -7.9 | -10.1 | -12.2 | -14.5 |

| Underlying GGB (% GNI*) | -1.8 | -2.3 | -2.8 | -3.2 | -3.6 |

Source: Central Bank of Ireland Projections

Note: Underlying GGB excludes estimates of excess CT and receipts from the Apple state aid case; (f) is forecast

The underlying GGB is projected to remain in deficit over the medium term

Figure 21: General government balance, per cent of GNI*

Source: CSO and Central Bank of Ireland. Chart data in accessible format. (XLSX 145.89KB)

Note: Underlying GGB excludes Central Bank estimates of excess corporation tax receipts and receipts from Apple State aid case; CJEU is Court of Justice of EU ruling on Apple state aid case.

Gross voted Exchequer spending projections for 2025 have been revised upwards

Figure 22: Gross voted expenditure, € billion

Source: Department of Finance and Department of Public Expenditure, Infrastructure, Public Service Reform and Digitalisation. Chart data in accessible format. (XLSX 145.89KB)

Note: The estimated expenditure outturn for 2025 includes an assumed additional €800 million in expenditure for 2025 on top of the projection in Budget 2026, informed by the Supplementary Estimates published by the Department of Public Expenditure, Infrastructure, Public Service Reform and Digitalisation in November 2025.

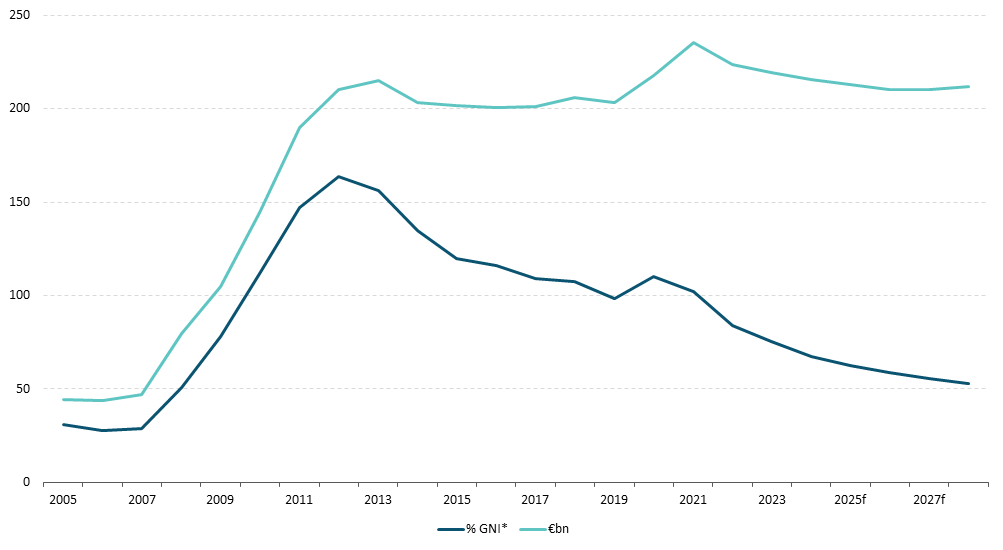

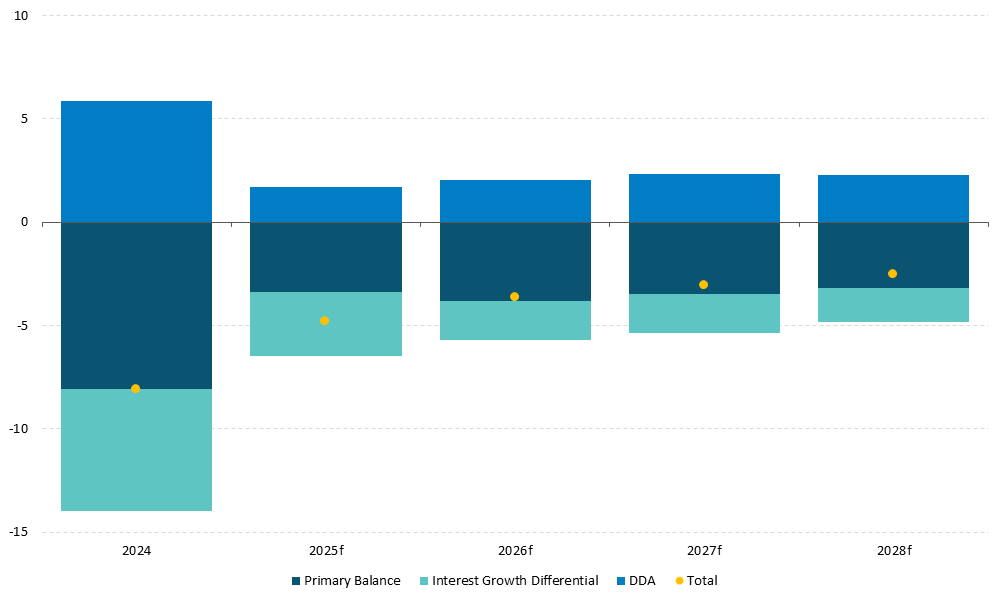

The General Government debt (GGD)-to-GNI* ratio is expected to continue to decline over the forecast horizon. The GGD ratio is projected to fall to 53 per cent by 2028 (Figure 23). The expected improvement reflects a combination of projected large headline primary surpluses (averaging 3.4 per cent of GNI* over 2025-2028) and a continuing favourable interest rate-growth rate differential (Figure 24). Nominal GNI* growth is expected to average 5.6 per cent per annum over the period 2025-2028, well above the projected average effective interest rate on government debt of 1.9 per cent. The National Treasury Management Agency (NTMA) has completed its funding plan for 2025, with bonds worth €8.25bn issued this year. Exchequer cash and liquid balances are currently high (€42.8bn at end November 2025), a figure that includes receipts from the Apple state aid case.

Debt ratio is projected to fall to below 60 per cent from 2026

Figure 23: General government debt, per cent of GNI* and € billion

Source: CSO and Central Bank of Ireland. Chart data in accessible format. (XLSX 145.89KB)

Headline budget surpluses and strong nominal growth are leading to reductions in the public debt ratio

Figure 24: Decomposition of the change in the debt-to-GNI* ratio per cent of GNI*

Source: Central Bank of Ireland. Chart data in accessible format. (XLSX 145.89KB)

Note: I-G Differential is interest rate-growth rate differential; DDA is the deficit-debt adjustment

Balance of Risks to the Outlook

The overall balance of risk to the forecast for economic growth is tilted to the downside. The central forecast envisages a slowdown in the pace of economic activity from 2026 onwards compared with the expected 2025 outturn, but the projections still imply a relatively benign overall outlook with steady growth and low unemployment. There are some developments that could result in the economy outperforming relative to the central forecast. These could include a larger increase in pharmaceutical exports if the current favourable global demand conditions improve further or from additional production capacity being realised. The latter could result in modified investment being stronger than projected in the central forecast. In addition, there is scope for the services sector to grow more quickly than forecast if recent high levels of AI-related investment by large MNEs in the sector globally translate into higher exports, value added and productivity in Ireland. However, the scope for growth to outperform the baseline if upside risks such as these materialise is limited in the short run, due to the binding capacity constraints in the economy at present caused by infrastructure gaps. Meanwhile, there are clear downside risks to the projections which would directly impart a negative impulse to economic growth. These include the potential for an escalation of global trade tensions and delays in relieving infrastructural deficits, both of which would reduce growth below the central forecast. This somewhat asymmetric position – the potential for higher growth being restricted but with downside risks that would transmit directly to lower activity – means that the overall balance of risk to growth is assessed to be to the downside.

There has been a reduction in trade-related uncertainty but global trade tensions continue to be high and the policy environment remains volatile, representing an important downside risk to the growth forecasts. Global trade tensions persist and the policy environment – in particular in the US – continues to be volatile. Medical and pharmaceuticals products and semiconductors – which together make up almost half of Ireland’s goods exports - are currently subject to ongoing Section 232 investigations by the US administration. While the EU-US trade agreement caps any potential future tariffs on these two sectors at 15 per cent, the risk remains that they could be subject to non-tariff changes to US industrial or tax policy that cause a reduction in current or future activity by MNEs in Ireland. In the short run, the public finances, exports and investment are particularly sensitive to such external developments, but the negative effects could ripple through to other parts of the economy in the form of lower incomes, employment and consumption.

Ireland’s concentrated exposures to foreign multinationals, particularly pharmaceuticals, semi-conductors and ICT services, introduces key sector and firm-specific risk to the forecast. At present, the concentration of activity in certain sectors is largely working in the economy’s favour. On the manufacturing side, there is a significant presence of MNEs in Ireland producing goods, such as ingredients used in weight-loss treatments, for which global demand is currently rising rapidly. There is the potential for exports to grow at a faster pace than projected in the central forecast if pharma production expands beyond current expectations. At the same time, just as the economy benefits when this sector is experiencing a cyclical upturn globally, a loss of market share or prolonged downturn in the performance of one or more individual firms poses a risk to overall export and import growth in Ireland, with related potential negative implications for employment and tax revenue. In relation to services, activity is similarly concentrated among a small number of globally significant multinationals. Valuations in US technology stocks are elevated as equity prices have risen to record highs, largely on the basis of these firms’ involvement in AI activities (Financial Stability Review 2025:II (PDF 1.41MB)). Many of these “Magnificent 7” firms have a significant employment presence in Ireland. As a result, it is possible that a large correction in equity prices arising from negative developments in the business models of these AI-related companies could result in lower exports, investment, employment and tax revenue in Ireland. These firms differ from their counterparts in the manufacturing sector as the required sunk investments in Ireland tend to be lower. As a result, the activity and employment arising from the MNE-dominated parts of the services sector is likely to be more footloose, and vulnerable to negative shocks.

Delays in addressing infrastructure deficits would impair the potential growth rate of the economy and exert upward pressure on inflation and costs. Through the Revised National Development plan and Budget 2026, the Government has allocated additional expenditure to much-needed infrastructure projects. Delays in the planning and delivery of capital projects need to be reduced so that the additional nominal expenditure translates into the delivery of new water, waste water, energy and transport projects where urgent improvements are needed. Should the reforms such as those included in the Accelerating Infrastructure report be implemented in an effective and timely manner, then there are some upside risks to the projections for housing output in particular. Against this, delayed progress resulting in persistent deficits in basic infrastructure would act as a drag on long-term growth by increasing business costs, lowering productivity and disincentivising new inward investment. While overall labour demand is trending downwards, difficulties in recruiting workers to key occupations such as those on the Critical Skills Occupations List may lead to upward pressure on wages in certain sectors and have a negative effect on Ireland’s competitiveness, reducing exports and overall growth in the medium run. Non-Irish citizens accounted for the majority of the growth in employment in the year to Q3 2025, an indication of the current importance of inward migration to fill key vacancies. Yet, the level of inward migration, as suggested by Employment Permits and PPSNs, appears to be down by one quarter over the year-to-date. This could reflect in part the negative effect of infrastructural constraints – such as housing and transport – on inward migration. Over an extended period, this could result in slower job growth than envisaged in the central forecast.

The balance of risks to the inflation outlook have shifted from being broadly balanced to being primarily to the upside. Unemployment is forecast to remain close to 5 per cent and employment is expected to continue to rise. In such circumstances, strong nominal wage growth and domestic demand could lead services inflation to be higher than expected. Inflation outturns in the services sector have been volatile of late, prompting an examination of the uncertainty surrounding estimates of underlying trend services inflation. Underlying trend inflation aims to capture the persistent, medium-term component of inflation, excluding volatility and noise. Underlying trend services inflation is not observed but can be estimated and shown alongside intervals (or uncertainty bands) which illustrate potential upside and downside risks, as well as the most probable trajectory (Figure 25). Underlying trend services inflation is estimated to have been broadly stable at 2.5 per cent on average from 2014 up to 2022. In the post pandemic period since 2022, estimated trend inflation has shifted upwards and has averaged 3.4 per cent from 2022 up to the present. Trend services inflation is estimated at 3.3 per cent as of October 2025, with a projected plausible range of 2.5 to 4 per cent for services in the foreseeable future. The current central estimate, along with the plausible lower and upper bounds for underlying trend services inflation, all remain well above their equivalent pre-pandemic levels.

Estimated trend services inflation has shifted onto a higher path in the post-pandemic period

Figure 25: Evolution of services inflation (outturns) and estimated trend component

Source: Central Bank of Ireland. Chart data in accessible format. (XLSX 145.89KB)

Notes: Trend is estimated using an Unobserved Component Model. Upper and lower bounds represent the 68% credible interval.

Bottlenecks in housing supply and high construction costs may continue to push up rents and housing-related inflation, which in turn could contribute to upward pressure on wages and goods prices. At the same time, in the absence of significant increases in construction sector productivity, the additional share of economic activity envisaged for this sector would see overall productivity in the economy be lower than would otherwise be the case, which in turn could amplify increases in unit labour costs and their pass-through to inflationary pressures. Any renewed spike in global energy or food prices due to geopolitical tensions could provide another source of additional inflationary pressures. Against that, a stronger euro or a slowdown in government expenditure growth could lessen inflationary pressures.

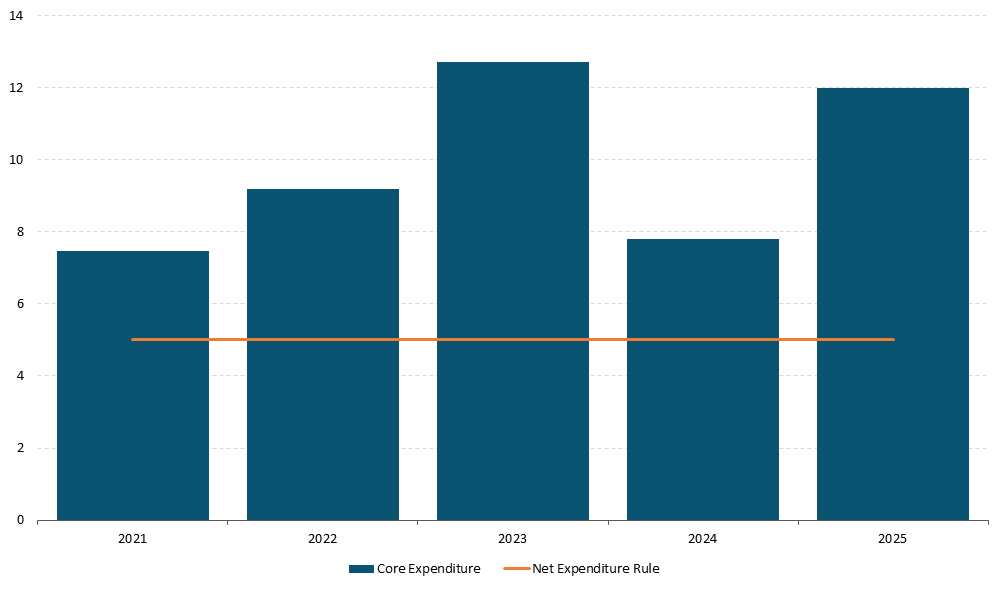

Government expenditure growth is running far in excess of the growth in tax revenue when excess CT is excluded, presenting a material downside risk to the public finances. The tax base is narrow with a particular vulnerability surrounding CT receipts, which represent one-third of all tax revenue. These receipts are highly concentrated, with two sectors (pharmaceuticals and ICT, both MNE-dominated) accounting for just over half of overall CT, according to Revenue’s report for 2024. An estimated 50 per cent of CT revenue is largely disconnected from underlying activity in the domestic economy and is vulnerable to a decline, potentially abruptly. While the EU and US have reached a trade agreement that sets a maximum 15 per cent tariff rate on pharmaceutical products, the impact on measured MNE profitability in Ireland remains uncertain. Apart from tariffs, other potential changes in US tax or industrial policy pose a downside risk to overall tax revenue, given the large contribution MNEs make to VAT and employment taxes as well as CT. Net government expenditure growth has averaged almost 10 per cent per annum since 2021, close to double the pace of increase envisaged in the now discontinued 5 per cent spending rule (Figure 26). Recent years have seen repeated in-year expenditure increases resulting in spending growth being revised above initial budget day plans and in a procyclical direction. A continuation of this trend would act to widen the underlying budget deficit. This risk is heightened by the absence of an effective anchor to guide the fiscal stance, in particular one that would align spending growth to the estimated sustainable growth of the economy.

Net government expenditure expected to be significantly higher than economy’s potential growth in 2025

Figure 26: Estimated net government expenditure growth, year-on-year growth

Source: Central Bank of Ireland. Chart data in accessible format. (XLSX 145.89KB)

Note: Net government expenditure is calculated as total general government spending less non-core spending less discretionary revenue measures. Accordingly, tax raising measures reduce net government expenditure while tax cutting measures increase net government expenditure in a particular year. The net expenditure rule in the Chart represents the previous government’s policy rule which aimed to keep net expenditure at or below the economy’s potential nominal growth rate of 5 per cent.

Detailed Forecast Table

Table 6: Baseline Macroeconomic Projections for the Irish Economy

(annual percentage changes unless stated)

| | 2024 | 2025f | 2026f | 2027f | 2028f |

|---|

Constant Prices | | | | | |

| Modified Domestic Demand | 1.8 | 3.9 | 3 | 2.8 | 2.8 |

| Modified Gross National Income (GNI*) | 4.8 | 4.8 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 2.9 |

| Gross Domestic Product | 2.6 | 12.8 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 3.3 |

| Final Consumer Expenditure | 3.0 | 2.9 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 1.9 |

| Public Consumption | 4.8 | 4.0 | 3.4 | 2.7 | 2.4 |

| Gross Fixed Capital Formation | -28.5 | 37.9 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 3.0 |

| Modified Gross Fixed Capital Formation | -4.2 | 6.5 | 4.4 | 4.5 | 5.2 |

| Exports of Goods and Services | 8.6 | 9.2 | 2.9 | 3.5 | 3.4 |

| Imports of Goods and Services | 2.7 | 6.6 | 2.4 | 3.0 | 2.9 |

| Total Employment | 2.7 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.7 |

| Unemployment Rate | 4.3 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) | 1.3 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 1.8 | 1.9 |

| HICP Excluding Food and Energy (Core HICP) | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 1.9 | 2.1 |

| Compensation per Employee | 4.3 | 4.6 | 4.0 | 3.7 | 3.5 |

| General Government Balance (% of GNI*) | 7 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 2.3 | 2 |

| ‘Underlying’ General Government Balance (% of GNI*)[13] | -1.8 | -2.3 | -2.8 | -3.2 | -3.6 |

| General Government Gross Debt (% of GNI*) | 67.1 | 62.3 | 58.6 | 55.5 | 53 |

| Modified Investment (% of Nominal GNI*) | 19.2 | 19.9 | 20.4 | 20.8 | 21.3 |

Revisions from previous Quarterly Bulletin, p.p | | | | | |

| Modified Domestic Demand | 0.0 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.4 | - |

| Gross Domestic Product | 0.0 | 2.7 | -0.7 | -0.8 | - |

| HICP | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.4 | - |

| Core HICP | 0.0 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.5 | - |

Box A: Real-Time Data Revisions and Nowcasting – Navigating Uncertain Signals in the Irish Economy

by Thomas Conefrey and Graeme Walsh

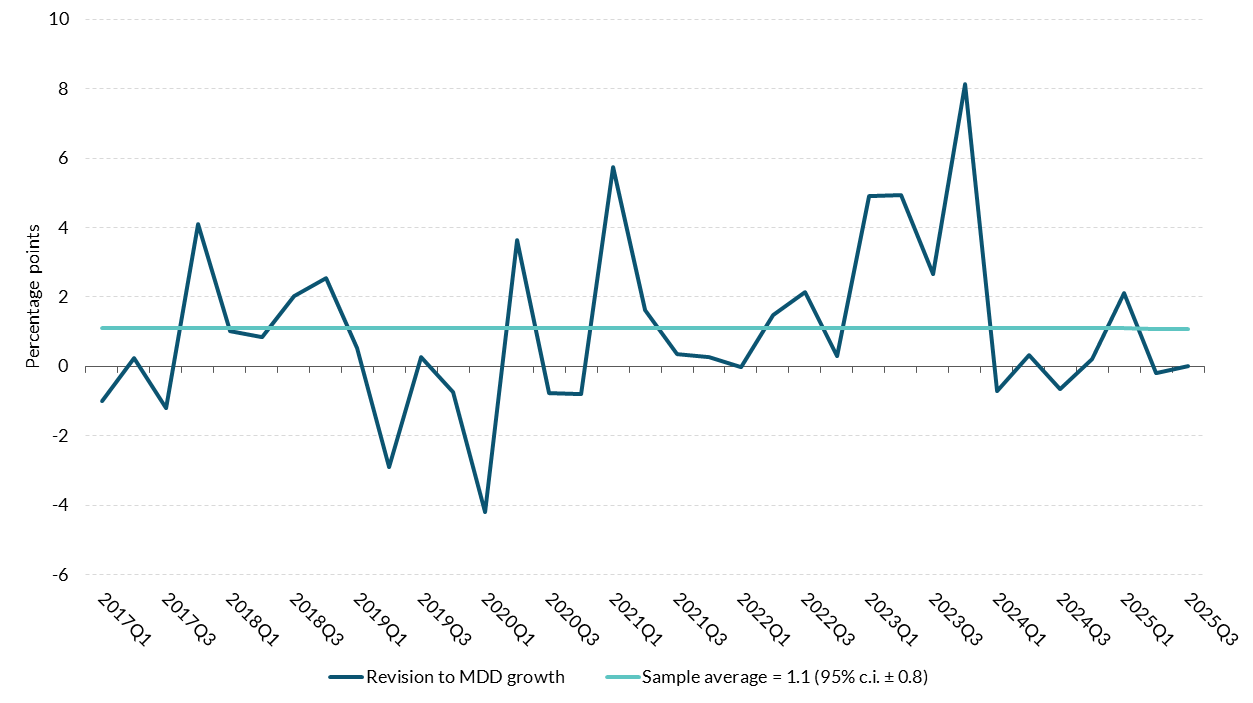

Assessing the Irish economy in real-time is complicated by the fact that Quarterly National Accounts (QNA) data are revised and published with a lag of around nine weeks. QNA data for Ireland are published in line with international standards and it is standard practice across countries for these data to be revised over time as new and additional information becomes available. Casey and Smyth (2016) and McCarthy (2004) show that Irish macroeconomic data are notably more volatile and subject to larger revisions compared to other countries. This presents a challenge for economic analysis since it introduces uncertainty in providing a clear assessment of economic conditions in the most recent quarter. The purpose of this Box is twofold. First, we document the pattern of revisions to the QNA estimates of Modified Domestic Demand (MDD) growth over time. We focus on MDD as it serves as the most widely used quarterly indicator of domestic economic activity in Ireland. Secondly, we evaluate the real-time performance of two Central Bank nowcast models that are used for producing early estimates of MDD growth ahead of the official CSO release. The nowcast models use the Central Bank’s Business Cycle Indicator (BCI) and employment growth as timely proxies for activity in the domestic economy. We find that the nature and magnitude of the revisions to MDD suggest that initial estimates should be interpreted with caution, considering the potential for future revisions. Nowcasting can be helpful for generating advance estimates of MDD growth in the current quarter but is inevitably subject to errors.

Revisions to official estimates of MDD

To analyse historical revisions to MDD, we use the Central Bank’s real-time database of the Quarterly National Accounts. This database contains 112 vintages of the QNA, dating back to 1999Q1. The real-time data reflect the information available at each point in time (i.e. the initial releases), which differ from standard macroeconomic data (i.e. the latest QNA release) that contains all information available up to today. MDD was first published in the first quarter of 2017 and so our analysis is confined to the 2017Q1 to 2025Q3 period over which real-time MDD estimates are available.

Figure 1 shows the revisions to MDD growth, with a revision defined as the latest MDD growth rate (i.e. QNA 2025Q3) for a given quarter minus the initial MDD growth rate estimate for that quarter. Positive (negative) values represent upward (downward) revisions to observations. The MDD growth rates from the initial releases are generally lower than the latest MDD growth rates (i.e. the blue line tends to be above zero). This reflects the tendency of initial estimates of MDD growth to be subsequently revised upwards. The period around the onset of the COVID pandemic is, however, an exception to this general trend as the initial estimates tended to be revised downwards, instead. Analysis of these real-time revisions to MDD growth reveals that initial estimates are revised upwards 70 per cent of the time, with an average increase of 1.1 percentage points. A statistical test confirms that this average revision is statistically significant, with a 95 per cent confidence interval of ±0.8 percentage points. Larger revisions are typically incorporated into the July QNA release, which coincides with the release of the more information-rich Annual National Accounts by the CSO.

Initial estimates of MDD growth tend to be revised up by 1.1 percentage points

Figure 1: Real-time revisions to MDD growth

Source: CSO data and Central Bank of Ireland calculations. Chart data in accessible format. (XLSX 27.17KB)

Tracking the economy in real-time using the BCI