Key Insights

Income tax’s share of total tax revenue (excluding excess corporation tax) has remained broadly stable since 2011 and above its values between 1996 and 2008, indicating that budgetary policy since the financial crisis of the late 2000s has not undermined this important source of Exchequer revenue.

Compared to what occurred between 1996 and 2008, the net costs of income tax packages, as a percentage of the previous year’s income tax revenue, in Budgets since 2015 have been modest in terms of their estimated impact on the income tax take.

For single taxpayers, the changes in average income tax rates between the 2013 and 2025 tax codes are small, with some shifting of income tax paid between its USC and non-USC components occurring.

Introduction

Budgetary policy has supported income tax as a revenue source

A contributing factor to the deterioration in the Irish public finances during the recession of the late 2000s was a sharp fall in income tax revenue[1]. Budgetary policy in the years preceding that event had reduced personal income tax rates and narrowed the income tax base (Cronin, Hickey and Kennedy, 2015) but strong growth in employment and taxable income maintained positive income tax growth.[2] When the economic downturn occurred, Exchequer income tax revenue declined by 17 per cent between 2007 and 2010. In response, policy changes in the 2009 and 2011 Budgets led to a greater proportion of income taxpayer units paying tax, with the introduction of an income levy and then a Universal Social Charge (USC) playing an important role in that shift, and average tax rates rising across the income distribution.[3] Income tax revenue increased sharply in 2011 and its share of total tax revenue was higher in that year than in any of the 2000s.

This Insight examines how budgetary policy since 2011, a period of improved Irish economic performance after the crisis years of the late 2000s, has affected the income tax take and considers the impact of such changes on average tax rates across the income distribution. After the 2011 Budget, there were no noteworthy income tax changes until the mid-2010s. Thereafter, general income tax measures in Budgets have involved a reduction in the higher rate of income tax (from 41 per cent to 40 per cent in the 2015 Budget), increases in standard rate bands and personal and employee tax credits, and reductions in USC rates and changes in USC bands.

When excess corporation tax is excluded from the total tax take, income tax’s share of overall tax revenue has remained steady compared to the late-1990s and 2000s. The net cost of income tax changes in the Budgets between 2021 and 2025 increased, but those costs remained relatively small, as a proportion of the previous year’s income tax revenue, compared with that which arose in the early 2000s. An assessment of the current (2025) income tax code with that of 2013, indexed for average weekly earnings growth, indicates that taxpayers across a wide range of income ranges have seen little change in their average tax rates in the post-crisis period. These points are elaborated upon below.

Income tax – macro developments

Income tax as a share of total tax revenue

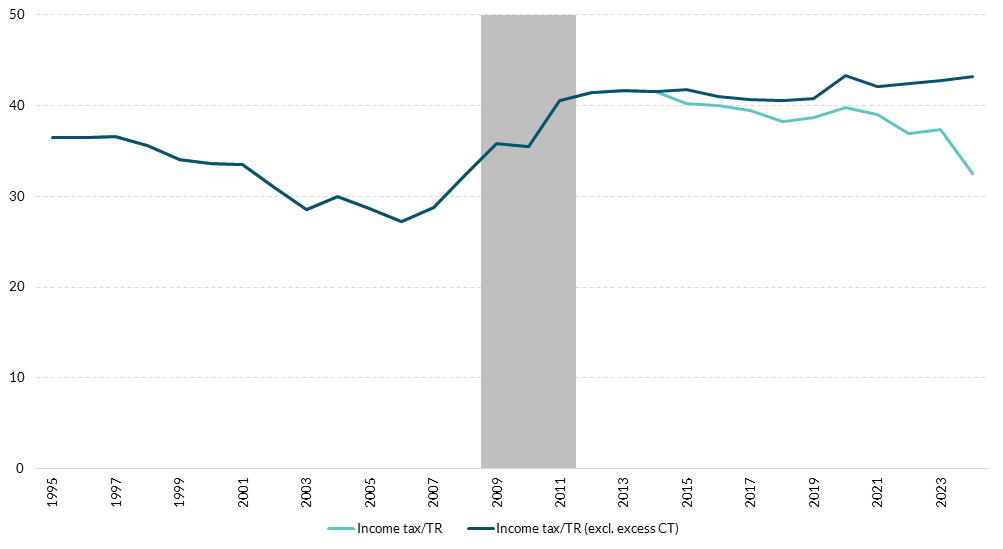

Income tax’s importance to the Irish public finances is highlighted by Exchequer data indicating it having the largest share of total tax revenue (TR) among the various tax headings in all bar seven years between 1995 and 2024.[4] Its annual share over that period is plotted in Figure 1. The shaded area in the chart covers the years 2009 to 2011 when major changes in income tax policy, involving greater taxation of income, took place. Income tax’s share of Exchequer revenue declined during the early-to-mid 2000s, falling to 27.2 per cent in 2006.[5] Its share increased from 32.3 per cent in 2008 to 40.5 per cent in 2011, with the sharpest year-on-year rise, of five percentage points, occurring between 2010 and 2011.

Income tax’s headline share of total tax revenue (the solid line in Figure 1) has declined since the mid-2010s. Excess corporation tax (CT) has been identified as a factor affecting total revenue in Ireland since 2015.[6] When estimates of such excess tax are subtracted from total revenue, income tax’s share of the adjusted total revenue (the dark blue line in Figure 1) has moved in a band of 2.8 per cent from 2011 to 2024, a considerably narrower range, and at a higher average, than that which arose between 1996 and 2010.[7] The number of income taxpayer units has also risen since 2012, but not to the same extent as overall income tax revenue.[8] [9]

Income tax’s share of adjusted tax revenue is higher than before 2011

Figure 1: Income tax’s share of total tax revenue, Exchequer basis

Source: DOF Exchequer Returns; Irish Fiscal Advisory Council; author’s calculations. Chart data available in accessible format.

Note: Horizontal axis covers the years 1995 to 2024. Vertical axis represents income tax’s share (%) of total tax revenue. Shaded area covers the years 2009 to 2011.

Accessibility: Get the data in accessible format. (CSV 18.94KB)

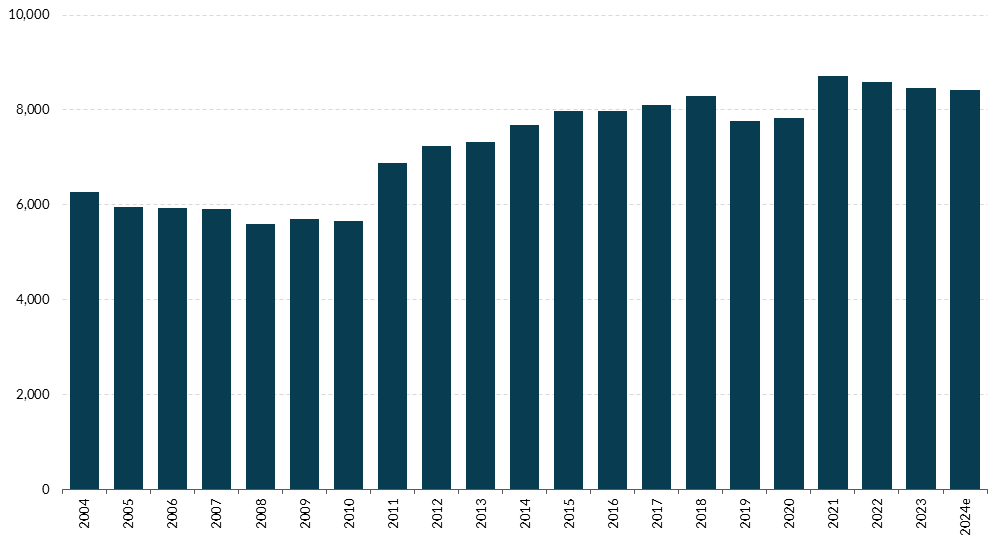

Income tax per taxpayer unit

Figure 2 shows the average income tax revenue per taxpayer unit (in 2015 prices, Exchequer basis) from 2004 to 2024.[10] Average revenue per unit generally declined from 2004 to 2010 but increased thereafter, as the introduction of USC and reductions in the standard income tax band took effect. Real compensation per employee also started to rise after 2015, which of itself helped income tax revenue growth. The average income tax take per taxpayer unit continued to increase until 2018 and then declined in 2019 and 2020, before recovering in 2021 to its highest within-sample value. It then fell in each of the following three years (by 3.5 per cent between 2021 and 2024).[11] Average income tax revenue per taxpayer unit in recent years, nevertheless, remains well above 2000s levels and is also higher than 2010s values.

Average income tax per unit has been high in recent years

Figure 2: Average Income Tax Revenue per Taxpayer Unit

Source: Revenue; Tax Strategy Group; Department of Finance; EU AMECO; author’s calculations. Chart data available in accessible format.

Note: Horizontal axis shows years 2004 to 2024. Vertical axis indicates average income tax revenue (€) per tax head in 2015 prices.

Accessibility: Get the data in accessible format. (CSV 0.84KB)

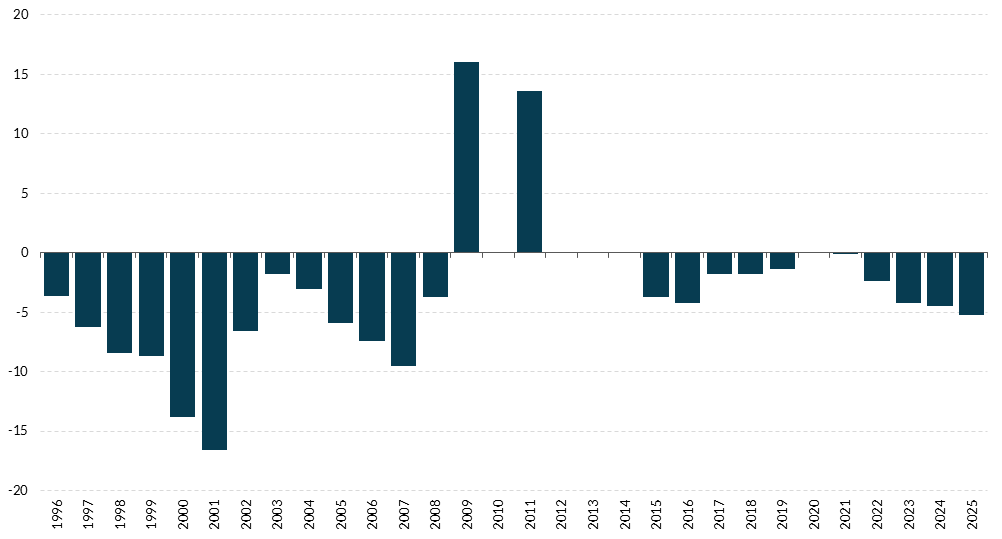

Income tax and budgetary policy

Figure 3 gives an indication of how budgetary policy has affected income tax revenue over the past thirty years or so, with the net full-year cost/benefit of Budget income tax packages shown as a proportion of the previous year’s Exchequer income tax revenue. The years from 1996 to 2008 were marked by two phases of rising income tax “giveaways”, from 1996 to 2001 and from 2003 to 2007, that acted to reduce income tax revenue to the Exchequer. The net costs of the income tax reductions in the 2000 and 2001 Budgets were extremely large. The tax reductions that followed up to 2008 were more modest but still acted to reduce income tax revenue. When property-related tax revenues collapsed and the broader economy contracted in the late 2000s, the impact of the narrowing of the income tax base and the reduction in effective income tax rates in previous years became apparent, with income tax revenue declining by 17 per cent between 2007 and 2010. The deterioration in the outlook for the public finances in 2008-9 saw two Budgets arising for 2009 with a new income levy introduced to boost tax revenue. In the 2011 Budget, the income levy, and the health levy, was replaced by the USC, while standard rate bands and personal and employment credits were reduced. The 2009 and 2011 budgetary measures were estimated to be raising a substantial amount of income tax revenue.

Recent income tax reductions have been relatively modest

Figure 3: Net full-year cost/benefit to Exchequer of general income tax changes in Budgets

Source: Department of Finance; author’s calculations. Chart data available in accessible format.

Note: Horizontal axis covers the years 1996 to 2025. Vertical axis shows net full-year cost/benefit to Exchequer of income tax changes in Budget as a percentage of previous year’s Exchequer income tax. A positive value indicates that the net effect of income tax measures adopted in the Budget was estimated by the Department of Finance at the time they were adopted as acting to increase revenue. A negative value indicates that the tax measures in toto acted to reduce income tax revenue.

Accessibility: Get the data in accessible format. (CSV 1.59KB)

There were no net changes to the general income tax code in the 2012 to 2014 Budgets that had a material impact on income tax revenue. There were reductions in income tax from measures adopted in the 2015 to 2019 Budgets (affecting both bands and credits and the USC but more heavily weighted towards the latter).[12] There were little or no changes in the income tax code in the Budgets during the pandemic years of 2020 and 2021, a period marked by higher government payments to households and businesses and a deterioration in the budget balance from a position of surplus to one of deficit. Since the 2022 Budget, there has been a steady rise in the full-year cost of the income tax measures in the Budgets. The tax reductions in those years have been more concentrated in tax credits and bands than in the USC code.[13] The full-year cost of the income tax changes in the 2025 Budget, as a percentage of the previous year’s income tax revenue, was the highest of the past ten years but was much less than what arose in many of the years between 1998 and 2007.[14]

Income tax – micro developments

The 2025 tax code compared to that of 2013

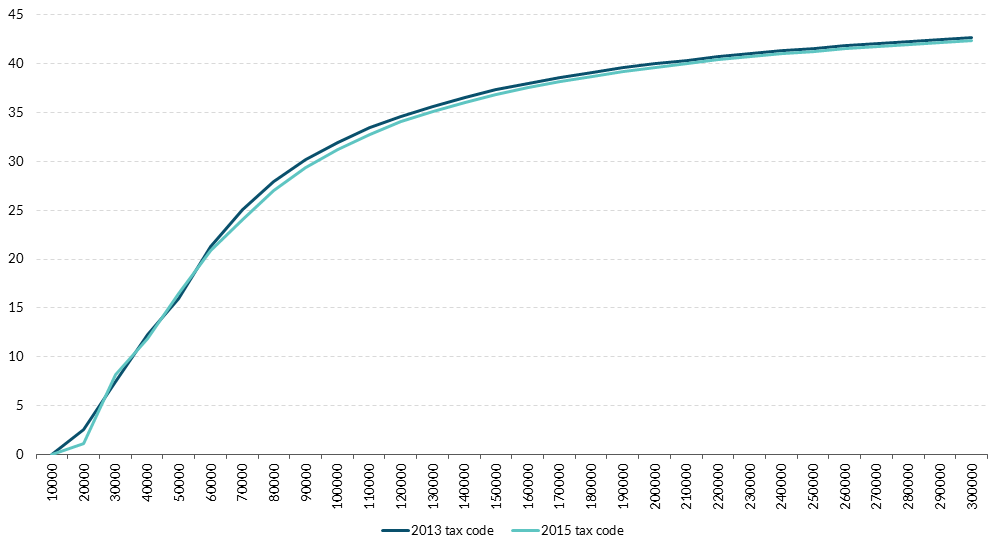

In this section, the average (combined USC and non-USC) tax rate under the 2025 Budget income tax code is compared to what would prevail were the 2013 tax code to have remained in place, allowing for indexation of bands and credits.[15] The focus is on one category of income taxpayer, the single (non-married) earner.[16] The 2013 tax code took account of the large tax policy changes in the 2009 and 2011 Budgets and arose before the first post-2008 (net) income tax reductions in the 2015 Budget.[17] The 2025 tax code reflects the increase in bands and credits, and changes in income tax and USC rates, in the 2015 Budget and subsequent Budgets. The method used in calculating average tax rates in 2025 were the 2013 tax code to apply in that year is to assume that the standard rate tax band, tax credits and USC bands in the 2013 code were increased in line with the rise in average weekly earnings (all NACE sectors) from 2013Q1 to 2025Q1, as per CSO data.[18] The particular standard and higher income tax rates and USC rates in place in 2013 are then used to calculate average tax rates under that year’s tax code applied to 2025. Consequently, the average tax rates being paid in 2025 following Budget 2025 can be compared to that which would pertain under the 2013 tax code, allowing for indexation only. Figure 4 shows the average (combined USC and non-USC) tax rates across the annual income range €10,000 to €300,000 (at €10,000 increments) under the two income tax codes for the single person taxpayer unit. In general, there is little change in the average tax rates of single taxpayers between the 2013 tax code, indexed for changes in average weekly earnings between 2013 and 2025, and the 2025 code itself.

Income tax rates have seen little general change

Figure 4: Average income tax rate (% of income)

Source: Budget books, author’s calculations. Chart data available in accessible format.

Note: Horizontal axis shows incomes over the range €10,000 to €300,000 at €10,000 increments. Vertical axis shows average tax rate (percent of gross income) at each increment.

Accessibility: Get the data in accessible format. (CSV 3.48KB)

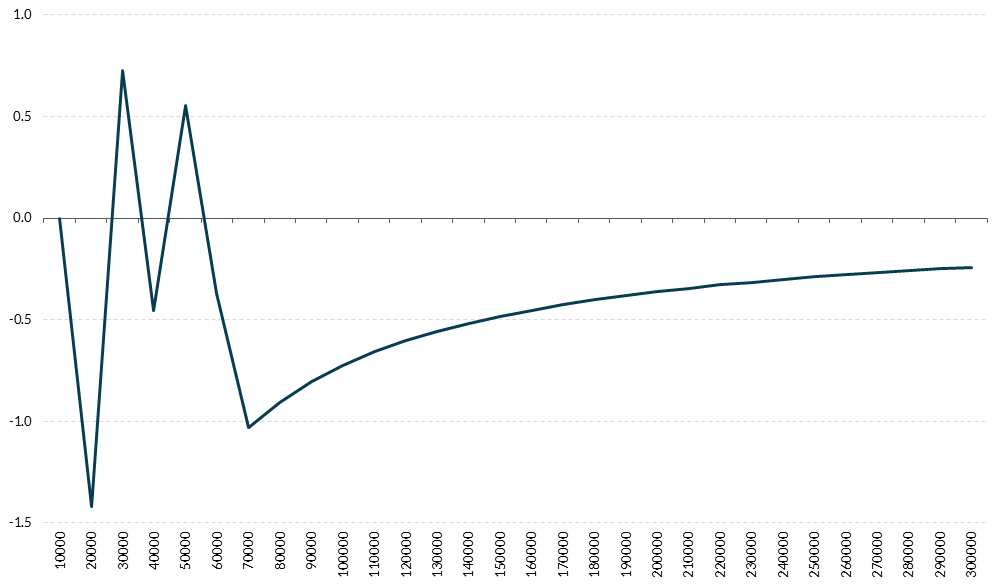

Figure 5 plots the differences, across the displayed income range, between the average tax rates of both codes being in a range of -1.4 to 0.7 percentage points, with the largest differences occurring at lower income levels. While those on an income of €70,000 pay an average tax rate that is one percentage lower under the 2025 tax code (down from 25.1 per cent to 24.1 per cent), the reductions in the average tax rates declines and tapers off gradually as income increases above that level. The single taxpayer earning €300,000 has an average tax rate under the 2025 tax code that is one-fifth of one percentage point lower than that of the indexed 2013 code.

Most average tax rates have changed by less than one percentage point

Figure 5: Change in average income tax rate

Source: Budget books, author’s calculations. Chart data available in accessible format.

Note: Horizontal axis shows incomes over the range €10,000 to €300,000 at €10,000 increments. Vertical axis shows the change in average tax rate (percentage points) at each increment between the 2013 and 2025 tax codes.

Accessibility: Get the data in accessible format. (CSV 0.55KB)

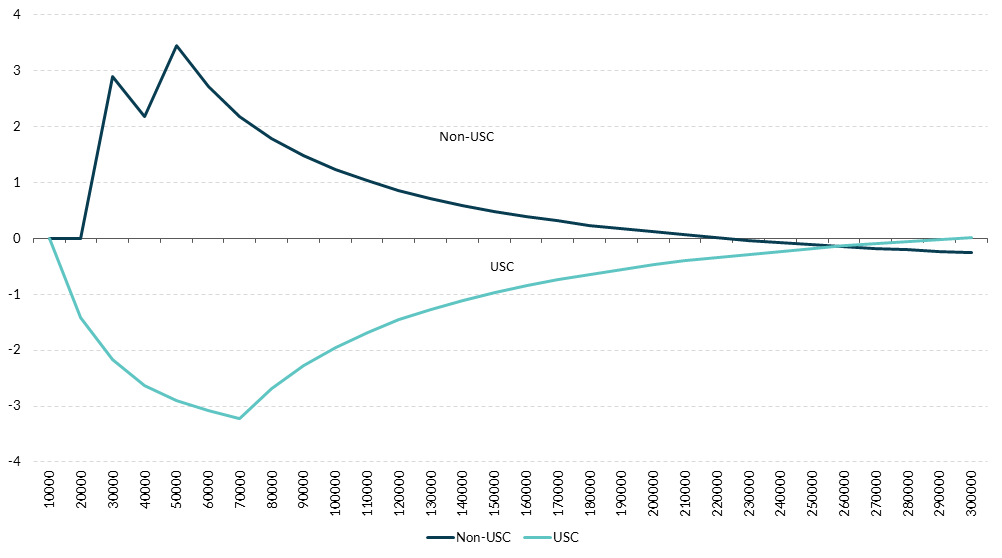

Changes in USC and non-USC components

Tax policy changes in Budgets between 2013 and 2025 affected both the non-USC and USC components of income tax. Figure 6 indicates the extent to which average rates under each component are affected. It shows that the average non-USC tax rates increased between the 2013 and 2025 codes for incomes between €30,000 and €210,000, with the largest increase arising for those earning €50,000 (a rise of 3.5 percentage points). Those earning €220,000 and above see a small decrease in their average non-USC tax rate. The chart shows substantial reductions in average USC rates between the 2013 and 2025 tax codes for those at the lower end of the income distribution. The drop in rates exceeds two per cent for those earning between €30,000 and €90,000, with decreases in average rates towards the middle of that range exceeding three per cent. The relatively large rise in non-USC average tax rates for those earning €70,000, and incomes close to that level, is largely or more than offset by a lower average USC rate. Those with incomes exceeding €200,000 see little reduction in their average USC rate between the 2013 and 2025 tax codes.

There have been larger changes in non-USC and USC rates

Figure 6: Changes in average non-USC and USC rates (percentage points)

Source: Budget books, author’s calculations. Chart data available in accessible format.

Note: Horizontal axis shows incomes over the range €10,000 to €300,000 at €10,000 increments. Vertical axis shows the changes in average non-USC and USC tax rates (percentage points) at each increment between the 2013 and 2025 tax codes.

Accessibility: Get the data in accessible format. (CSV 0.53KB)

Conclusion

In the round, budgetary policy since the economic crisis of the late 2000s and early 2010s has not undermined income tax receipts, an important source of Exchequer tax revenue. In particular, average tax rates at higher incomes, from where a large share of income tax is collected, have seen little change.[19] The strong year-on-year growth in income tax revenue and its maintaining a steady share of total tax revenue has been supported by rising gross income, reflecting wage and employment growth.

The OECD’s annual Taxing Wages publication provides an international comparison of income tax rates across its 38 country members. In 2024, income tax as a proportion of gross wage earnings in Ireland (for both single and married taxpayer units) is higher than the OECD average and that of its 22 EU country members.[20] (If employee social contributions are included, the resultant combined personal average tax rate in Ireland is closer to its EU peers, as the rates for these contributions are much lower in Ireland.[21]) A measure of the progressiveness of a country’s income tax system can be calculated using the OECD data by dividing the average income tax rate for a single person (no children) earning a gross income of 167 per cent of the average wage by the equivalent rate for the person earning 67 per cent of the average wage. The value of 2.37 for Ireland in 2024 is substantially higher than the OECD average of 1.88 and its EU-22-membership average of 1.91.

While the OECD data indicate that Irish taxpayers pay a relatively high average rate of income tax, and the Irish income tax system is highly progressive in comparison to other countries, recent income tax changes seem to echo the motivations of Budgets from 1999 to 2007, namely to reduce the income tax burden on the lower paid.[22] The Tax Strategy Group (2022, p.7) has also noted that "taking account of the economic recovery, since 2015 Government policy has focused on reductions to income tax targeted at low to middle income earners."[23] However, past experience, including the economic shocks of the late 2000s, highlights the risks of discretionary reductions to the tax base and effective income tax rates in general, or to re-adjusting the tax code excessively across the income distribution in favour of the lower paid. Such actions can weaken the robustness of income tax revenue.[24] Income tax policy, and tax policy more generally, must also take account of growth in government expenditure, which has been quite strong in recent years, so as to ensure that the public finances remain on a sustainable path.

Endnotes

- The views expressed here are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Central Bank of Ireland or the European System of Central Banks. The author would like to thank Bank colleagues, particularly Martin O’Brien, Thomas Conefrey and Niamh Hallissey, for their helpful comments and suggestions. ↑

- Cronin, D., Hickey, R., and Kennedy, G. (2015), “How budgetary policy has shaped the Irish income tax system.” Administration, 62, 4, 107-118. ↑

- Since 2011, income tax in Ireland comprises USC and tax calculated on the basis of standard rate bands, tax credits and standard and higher tax rates (referred to here as non-USC income tax). Pay-related social contributions are not considered here. ↑

- Source: https://databank.finance.gov.ie/FinDataBank.aspx?rep=TaxYrTrend ↑

- Income tax fell below value-added tax to be the second largest source of Exchequer tax revenue between 2003 and 2008. Corporation tax receipts exceeded income tax revenue in 2024 owing to receipts arising from the CJEU ruling of September 2024. ↑

- Recent discussions of this influence on Exchequer tax revenue include Boyd et al. (2025) (PDF 0.98MB) and Irish Fiscal Advisory Council, Fiscal Assessment Report, December 2024 ↑

- The estimate of excess corporation take here relies primarily on the Irish Fiscal Advisory Council, Fiscal Assessment Report, December 2024 report. Figure 9 therein provides a measure of both total revenue and total revenue excluding excess corporation tax on a General Government basis and stated as a percentage of GNI*. The difference between those two series and CSO outturn data for GNI* allow the euro amount of excess corporation tax to be calculated for the years 2015 to 2023. It is assumed that the Exchequer measure of this tax equates with the General Government calculation.

Table 13 of Budget 2025: Economic and Fiscal Outlook indicates that excess corporation tax in 2024 would amount to €15.9bn, while additional one-off proceeds from the CJEU ruling of September 2024 would amount to €14.1bn. The End-2024 Exchequer Returns indicate that €10.9bn of those proceeds were received by the Exchequer in 2024. Thus, excess corporation tax, on an Exchequer basis, in 2024 is estimated at €26.8bn. ↑

- As noted in Statistical Classification of Taxpayer Units, Revenue publishes its statistics on income tax on a taxpayer unit basis, owing to the way in which married couples and civil partners are assessed. There are six types of unit: single males, single females, married couples – both earning, married couples – one earning, widows, and widowers. ↑

- There were 2.1 million income taxpayer units in 2012, broadly equivalent to the number in 2004. The number of taxpayer units rose steadily after 2012, reaching 3.4 million in 2024. Taxpayer unit data from 2004 to 2023 are sourced from Revenue’s website, with estimates for 2024 being projected taxpayer units provided in Tax Strategy Group documents. ↑

- Average tax revenue per taxpayer unit is calculated as Exchequer income tax revenue divided by taxpayer unit numbers. The CPI data are from the EU AMECO database. ↑

- Again, a caveat is that the taxpayer unit number for 2024 is a projected, not a confirmed, number. ↑

- Across five Budgets (2015 to 2019), the cumulative nominal full-year costs of the measures were €718 million for the bands-and-credits measures and €1,668 million for the USC measures. The 2015 Budget income tax reductions included a decrease in the higher rate of tax from 41 per cent to 40 per cent. ↑

- The nominal cost of USC reductions between the 2022 and 2025 Budgets was €973 million while those arising in the non-USC component amounted to €4,248 million (that amount includes the costs of changes to non-mandatory reliefs such as the home carer tax credit, dependent relative tax credit and other non-universal income tax measures). ↑

- The 2026 Budget saw a general income tax package, at a full-year cost of €26 million, that was much smaller than that of any Budget since 2021. ↑

- Alongside the USC code, the general income tax code (involving standard and higher tax rates, standard rate band, and employee tax credit (assuming the taxpayer is a PAYE employee) and personal tax credit) is applied. The impact of more specific allowances, such as the single person-child carer tax credit, is not considered. ↑

- In 2023, the last year for which Revenue has published such data, this category of taxpayer accounted for 42 per cent of gross income (41 per cent in 2013) and 63 per cent of taxpayer units (57 per cent in 2013). A further 42 per cent of gross income in 2023 was in the married couples – two incomes category. Calculating effective average tax rates for that category is not considered as such couples can transfer allowances between themselves. Married couples – one income (13 per cent of gross income) and widows and widowers (3 per cent) represent the other income categories. ↑

- The year 2013 is chosen from that period as it was the final year used in Cronin et al (op. cit.). The estimated average income tax rates for that year would differ little between those in 2011 and 2014, as the general income tax code saw little change in those years and changes in earnings rates were small at that time. ↑

- Changes in nominal earnings/wages and in the consumer price index can be used as alternatives to one another for indexing tax bands and credits in this form of exercise. For a discussion of this issue, see: Balladares, S., and E. Garcia-Miralles (2024), “Fiscal Drag: The Heterogeneous Impact of Inflation on Personal Income Tax Revenue.”, Banco de Espana Occasional Paper 2422; Doorley, K., and C. Keane, “Statement to the Committee on Budgetary Oversight; February 2nd, 2022”. ↑

- Taxpayers with gross income of €100,000 or higher accounted for 56 per cent of income tax revenue (income tax and USC) in 2022 (Boyd et al., op.cit, p. 12). ↑

- See Table 3.4 in Taxing Wages 2025, OECD (30 April 2025) ↑

- See Table 1.3 in Taxing Wages 2025, OECD (30 April 2025) ↑

- See, for example, the Financial Statement - 2007 Budget of the Minister of Finance on 6 December 2006. ↑

- Tax Strategy Group (2022), Income Tax, 22/02 (July) ↑

- Box A in Boyd et al., op. cit., highlights how high earners, particularly in the MNE and traded sectors, currently accounting for a large proportion of income tax revenue leaves the public finances exposed to any sectoral shocks that would affect those taxpayers adversely. ↑