Key Insights

Irish SMEs are expected to continue posting positive and stable profit margins under the central scenario for the domestic economy.

In an adverse scenario which assumes a sharp deterioration in the global and domestic macro-financial environment driven by heightened geoeconomic tensions, SME profit margins fall sharply. Sectors with the greatest trade exposures suffer the largest drop in profitability.

While the adverse scenario projects a large increase in the proportion of loss-making SMEs, the number of firms entering financial distress is more modest. This provides confidence in the resilience of Irish SMEs, even under stress conditions.

Introduction

A new economic environment

Irish Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) have proven their resilience to an array of economic headwinds in recent years – including the pandemic, energy, inflation, wage, and interest rate shocks. Despite these events, turnover, profitability, and balance sheet indicators have remained strong and robust over this time – with a small and stable share of SMEs reporting negative profit margins (Central Bank of Ireland, 2025a, 2024, 2023a, 2023b; Adhikari and Mahony 2024 (PDF 542.3KB)).

However, increased geoeconomic fragmentation, risk, and uncertainty (as exemplified by the US tariff declaration on April 2 2025) increasingly characterise the global economy. As highlighted by Central Bank of Ireland (2025b) (PDF 1.4MB), a weakened trading relationship between the US and EU is a leading medium-term risk to the Irish economy. Ireland’s economy has a dual nature (see for example, Central Bank of Ireland (2025b) (PDF 1.4MB), Mahony and O’Neill (2025), Department of Finance (2024)) – with both the multinational and indigenous aspects exposed to these geoeconomic headwinds. While the direct exposures of indigenous firms to geoeconomic headwinds are lower than the multinational sector, they are not completely insulated. For example, Central Bank of Ireland (2025b) (PDF 1.4MB) notes that over 80 per cent of Irish-owned firms in manufacturing, information and communications technology, and wholesale and retail sectors are involved in importing and/or exporting. More broadly, about two thirds of international trade by indigenous firms is with the EU and UK. A smaller share (15 per cent) is with the US and directly exposed to any fallout from US-EU geoeconomic fragmentation. Additionally, indigenous firms are exposed to indirect or spillover effects from weakened global trading relationships.

How do geoeconomic headwinds affect SMEs?

Given this economic context, how exposed are Irish SMEs (which account for 99.8 and 60.1 per cent of active enterprises and persons engaged, respectively) to geoeconomic headwinds? This is the purpose of this Insight, which examines how SME profit margins evolve under a baseline and adverse scenario over the next three years (i.e. 2025-2027). The baseline combines Central Bank of Ireland Quarterly Bulletin No. 2 2025 forecasts (QB) and the European Banking Authority (EBA) 2025 EU-wide stress test baseline scenario. The adverse is the EBA adverse scenario. In this hypothetical scenario, heightened geoeconomic headwinds (including geopolitical tensions and fragmented trade), higher inflation and persistent supply shocks drive a deterioration in the global macro-financial environment, which in turn leads to a decrease in output and higher unemployment. The difference in profit margins between these two scenarios directly captures the impact of this economic downturn, as well as spillover effects, on Irish SMEs.

Combining granular survey returns with these scenarios, this Insight answers three key research questions. First, what happens to SME profit margins in a severe (but plausible) macroeconomic scenario following a sharp deterioration in the global macro-financial environment? Second, are there any differences in outcomes between exporters and non-exporters? Third, will there be an increase in loss-making SMEs and will this have implications for financial stability?

How we simulate SME profit margins?

Measuring realised SME profit margins

SME profit margins are defined as the difference between turnover and expenditure, scaled by turnover (see Adhikari and McGeever (2023) (PDF 361.92KB) for further details). Realised SME profit margins for 2024 are calculated using granular firm-level survey data from the latest wave (2024) of the Department of Finance Credit Demand Survey (CDS). This annual survey (of around 1,500 SMEs) covers a range of firm characteristics as well as profit and loss variables, and is representative of NACE and size distribution of Irish SMEs. Due to their different structure, SMEs from industrial sectors K (financial and insurance activities) and L (real estate activities) are excluded – with a small decrease in sample size to 1,432 SMEs.

Combining the scenarios with the survey data

To simulate SME profit margins, SME turnover and the components of expenditure are shocked using a combination of QB and EBA projections for the baseline and adverse scenario. Table 1 outlines the projection variables used, as well as the components of SME profit margins they simulate. For example, gross value added (GVA) growth projections by sector (from the EBA) are used to shock SME turnover. This is the only variable where sectoral data is available – all other variables are projected at an aggregated level. Neither rent, tax nor commercial rates are projected in this exercise – but these only account for 12 per cent of median expenditure.

Table 1: Baseline and adverse shocks

| Projection Variable | Source | SME Profit Margin Component | | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 |

|---|

| Real GVA by sector | EBA | Turnover | Baseline | 3.9 | 4.3 | 3.5 |

| | | | Adverse | -0.5 | -3.4 | 0.5 |

| HICP | EBA | Purchases | Baseline | 2 | 2 | 1.5 |

| | | | Adverse | 3 | 2.5 | 0.2 |

| Compensation per employee | QB | Wages/salary costs | Baseline | 4.1 | 3.7 | 3.6 |

| | | | Adverse | 2.5 | 2 | 0 |

| HICP (energy) | QB | Utilities | Baseline | -0.7 | 1.5 | 1.9 |

| | | | Adverse | 11 | 11 | 11 |

SME profit margins in 2024

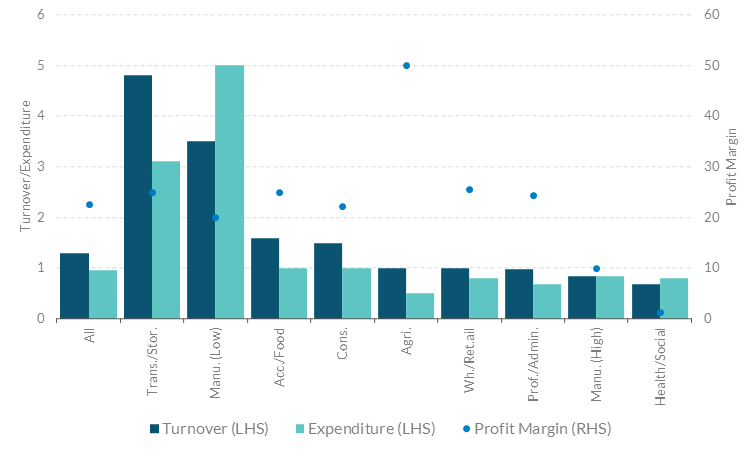

SMEs enter the start of our simulation in a strong position. We observe that in 2024 median SME turnover and expenditure was largely in line with 2023 values. Similarly, the breakdown of expenditure remains largely unchanged (with purchases and wages remaining the largest expenditure categories). This conforms to the trend of SME resilience discussed in the introduction. In 2024, median SME turnover was €1.3 million, with expenditure of €0.95 million (Figure 1). Both have witnessed modest increases since 2023 – turnover increasing by €0.1 million, and expenditure increasing by €0.05 million.

Heterogeneities across industries are noticeable regarding both variables. Transportation/storage and manufacturing (high energy usage) have the highest median turnover and expenditure – in both cases more than double the next highest industry (accommodation/food). Five industries have median turnover and expenditure below the overall (namely agriculture, wholesale/retail, professional/administrative, manufacturing (high energy usage) and human health/social work).

In 2024 median SME turnover was €1.3 million, with expenditure of €0.95 million

Figure 1: Median 2024 SME turnover and expenditure (in €m)

Source: Department of Finance Credit Demand Survey.

Note: Survey weights applied to SME responses. Industry NACE codes: H (transportation/storage), C (manufacturing), I (accommodation/food), F (construction), A (agriculture), G (wholesale/retail), MN (professional/administrative), and Q (human health/social work).

Accessibility: Get the data in accessible format. (CSV 0.37KB)

In 2024 for the median SME, purchases of goods/services and wages/salary costs accounted for a combined 65 per cent of expenditure. Of the remaining categories, taxation and other account for 20 per cent in total, while utilities (such as energy bills) are 5 per cent. Both rent and commercial rates make up only 1 per cent each. Furthermore, looking at the median SME within each sector purchases and wages are always the largest components.

What happens to SME profit margins in a severe macroeconomic downturn?

Aggregate Profit Margins

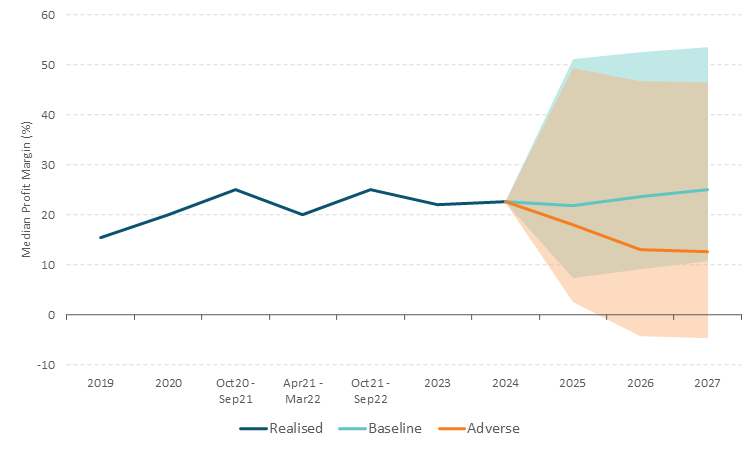

There is a large divergence between median profit margins in the baseline and adverse scenario, highlighting the exposure of Irish SMEs to geoeconomic fragmentation and risk (Figure 2). In the baseline, the median SME profit margin largely continues along realised trends. In 2023, it stood at 22 per cent and increases modestly to over 25 per cent by 2027. Only 2025 sees a modest dip, but this is offset by increases in 2026 and 2027. In addition, the interquartile range (indicating dispersion around this median) is always positive, remains steady and trends upwards – all confirming generally positive trend for Irish SMEs in the baseline. This is consistent with robust and stable resilience indicators discussed in the introduction.

In contrast, the adverse scenario sees a sharp reversal in recent profit margin trends. Rather than median profit margins increasing to 25 per cent by 2027, they decrease to below 13 per cent. This rate is close to the lower quartile in the baseline scenario. In fact, the median SME adverse profit margin decreases each year – with 2025 and 2026 witnessing the bulk of this decrease (at over 9 percentage point drop). In addition, the interquartile range widens from 2026 onwards – indicating a higher range of negative outcomes compared to the baseline. Furthermore, this environment leads to the lowest SME profit margins in over five years.

Large divergence between median profit margins in the baseline and adverse scenario

Figure 2: Median SME profit margins in the baseline and adverse scenarios

Source: Department of Finance Credit Demand Survey, Central Bank of Ireland QB No.2 2025, EBA 2025 EU-wide stress test.

Note: Survey weights applied to SME responses. Shaded regions refer to the interquartile range (IQR) – difference between the 75th and 25th percentile.

Accessibility: Get the data in accessible format. (CSV 0.46KB)

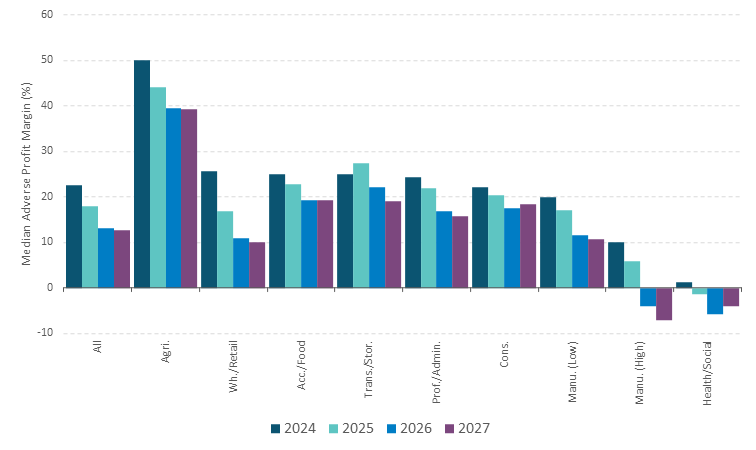

Profit Margins by Sector

The main conclusions from Figure 2, largely hold true for both scenarios at a sectoral level. For example, in the baseline median SME profit margins remain positive in all sectors. In contrast, the adverse witnesses sustained decreases through to 2027, with all sectors posting lower profit margins (Figure 3). However, median profit margins typically remain positive in this scenario – indicating the resilience of Irish SMEs to this severe economic downturn.

Median adverse profit margins decrease by 2027 in each sector, and in some sectors turn negative

Figure 3: Median SME profit margins in the adverse scenario by NACE

Source: Department of Finance Credit Demand Survey, Central Bank of Ireland QB No.2 2025, EBA 2025 EU-wide stress test.

Note: Survey weights applied to SME responses. Industry NACE codes: H (transportation/storage), C (manufacturing), I (accommodation/food), F (construction), A (agriculture), G (wholesale/retail), MN (professional/administrative), and Q (human health/social work).

Accessibility: Get the data in accessible format. (CSV 0.47KB)

Are there any differences in outcomes between exporters and non-exporters?

Which sectors have the largest number of exporting SMEs?

Central Bank of Ireland (2025b) (PDF 1.4MB) reports (components) of the manufacturing, wholesale/retail, professional/administrative, and transportation/storage as being the most exposed to international trade. We corroborate this finding, as these sectors have the highest propensity to export in the survey data. That is, these sectors have a higher percentage of exporting SMEs.

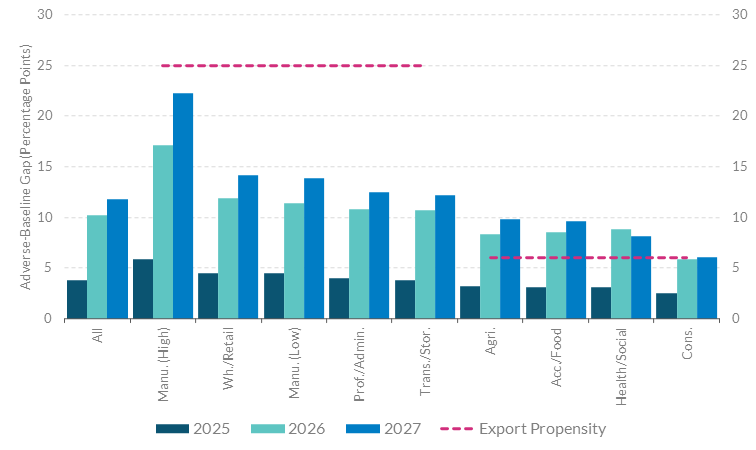

The adverse-baseline profit margin gap

The gap between median profit margins in the adverse and baseline scenarios increases each year, and the sectors with the highest export propensity tend to have a larger gap (Figure 4). In 2025, this gap is nearly 4 percentage points on average across sectors, but this increases to nearly 12 percentage points in 2027.

Gap between the adverse and baseline median profit margins increases each year in each sector

Figure 4: Adverse – baseline median profit margin gap by NACE

Source: Department of Finance Credit Demand Survey, Central Bank of Ireland QB No.2 2025, EBA 2025 EU-wide stress test.

Note: Survey weights applied to SME responses. Dashed lines refer to the export propensity averages within industrial groups.

Accessibility: Get the data in accessible format. (CSV 0.43KB)

This gap directly measures the impact on SMEs of a severe macroeconomic downturn following global disruptions. Industrial sectors with above average export propensity have the largest adverse-baseline gap, while those with below average have the smallest. In other words (and as expected), sectors with greater geoeconomic exposure witness a larger drop in profit margins relative to the baseline. Specifically, sectors with an above average share of exporters have a median adverse-baseline gap in 2027 of over 13 percentage points, while sectors with a below average share have a gap of 8 percentage points.

Will there be an increase in loss-making SMEs?

Lossmaking in the baseline and adverse scenarios

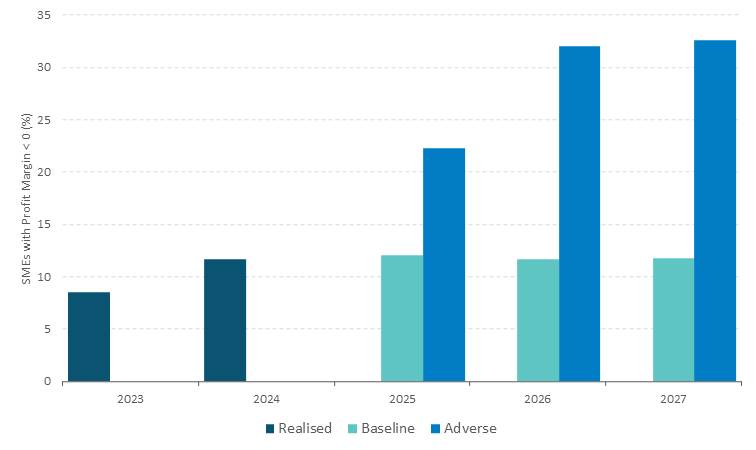

The percentage of loss-making SMEs remains unchanged in the baseline, but sharply increases in the adverse scenario (Figure 5). There was a modest increase in the percentage of SMEs with negative profit margins between 2023 and 2024 – an increase of 3 percentage points to around 12 per cent of SMEs. In the baseline scenario, the percentage of SMEs with negative profit margins remains steady at around 12 per cent between 2025 and 2027. In contrast, the adverse scenario sees a sharp increase in loss-making SMEs, with almost a third of SMEs having a negative profit margin by 2027. This follows a 10 percentage point increase in loss-making SMEs in both 2025 and 2026 (with only modest increase in 2027). While most loss-making SMEs have profit margins worse than -5 per cent, none of these losses in the adverse scenario can be classed as extreme.

Percentage of loss-making SMEs remains unchanged in baseline, but sharply increases in the adverse scenario

Figure 5: Percentage of SMEs with profit margins < 0 in baseline and adverse scenarios

Source: Department of Finance Credit Demand Survey, Central Bank of Ireland QB No.2 2025, EBA 2025 EU-wide stress test.

Note: Survey weights applied to SME responses.

Accessibility: Get the data in accessible format. (CSV 0.11KB)

Correspondingly, Table 2 shows the percentage of SMEs with non-negative profit margins in t-1 which transition to negative profit margins in year t. In the baseline, only a small percentage of SMEs transition from non-negative profit margins to negative ones – in both cases, well below 1 per cent of firms. In contrast, the adverse scenario sees larger transition rates – over 9 and 12 per cent in 2024-2025 and 2025-2026 (respectively). Again, 2026-2027 sees only a modest transition – reflecting the new normal induced by geoeconomic events.

Table 2: Percentage of SMEs transitioning to loss-making

| | 2024-2025 | 2025-2026 | 2026-2027 |

|---|

| Baseline | 0.07 | 0 | 0.26 |

| Adverse | 9.46 | 12.56 | 0.84 |

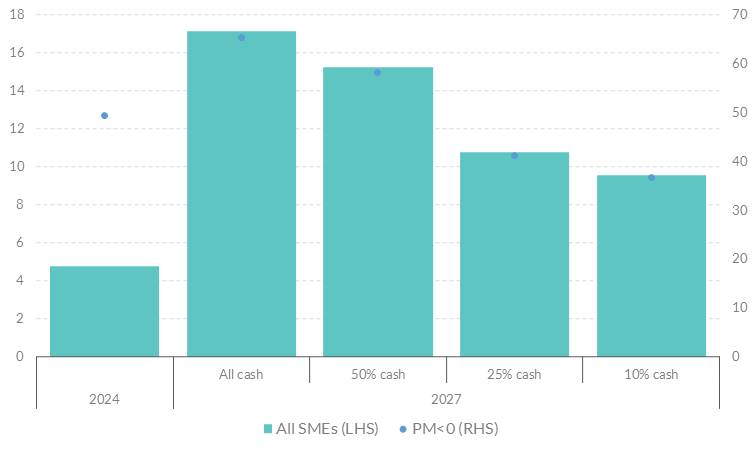

Testing the Resilience of Lossmaking SMEs

Given the large increase in loss-making SMEs in the adverse scenario, of prime importance is whether these firms remain resilient and avoid default or potential insolvency. To test this, we follow McCann and Yao (2021) (PDF 898.68KB), and define an SME as in liquidity distress if its cash covers less than three months of operational losses. At our starting point in 2024, 49 per cent of loss-making firms (or 5 per cent of all firms) breached this threshold (Figure 6). As losses continue to build over the three-year adverse scenario, SMEs have a number of options available to them (including preserving cash, selling assets, taking on more debt or seeking forbearance on some payments). In the short-run, using cash is the quickest and easiest way to maintain liquidity – and in this exercise we assume SMEs are willing to use some of their cash to cover their losses in the first two years. Specifically, we consider scenarios where SMEs cover all their losses using cash or only use a percentage of their cash to cover losses (namely, 50, 25, and 10).

We find that, despite an increase in loss-making firms, the resilience of SMEs remains strong with only a modest increase in the proportion in financial distress. Under plausible assumptions, in which firms seek to preserve some cash buffers, we estimate that 10-15 per cent of SMEs could be financially distressed by 2027. Even under the harshest assumption, where SMEs decide to use cash to cover all their losses, it only reaches 17 per cent – with the impacted firms only accounting for just over 11 per cent of SME employment. Where cash buffers are maintained, firms showing signs of financial distress only account for 6-10 per cent of SME employment. Our findings provide confidence in the resilience of Irish SMEs even during times of significant stress.

Despite an increase in the proportion of loss-making firms, the resilience of SMEs remains strong, with only a modest increase in the proportion of SMEs in financial distress

Figure 6: Percentage of SMEs (loss-making and all) in liquidity distress in 2024 and 2027 (adverse scenario), with different cash options

Source: Department of Finance Credit Demand Survey, Central Bank of Ireland QB No.2 2025, EBA 2025 EU-wide stress test.

Note: Survey weights applied to SME responses.

Accessibility: Get the data in accessible format. (CSV 0.11KB)

Conclusion

The purpose of this Insight is to consider future paths for SME profit margins. One path (the baseline) largely reflects a continuation of existing trends. If this scenario were realised, Irish SMEs would continue to report robust and stable profit margins. Furthermore, there is no substantial change in the proportion of loss-making SMEs. This is consistent with the well-documented post-pandemic performance of Irish SMEs.

In contrast, in the event of a severe global and domestic macro-economic shock, a very different trend for Irish SMEs emerges. In this adverse scenario, Irish SMEs see sustained decreases in profit margins to a new level over 12 percentage points below what they otherwise would have been. This pattern holds true across each industrial sector, although some sectors are harder hit than others. In line with expectations, the hardest hit are more globally exposed. Specifically, industrial sectors with above average export propensity have the largest adverse-baseline gap. There is a corresponding rise in the proportion of lossmaking SMEs – 21 percentage points above its baseline counterpart by 2027. Similarly, the proportion of loss-making SMEs with debt rises – increasing the risks of financial stability for these firms.

References

Adhikari, T., and Mahony, M. (2024). SME Repayment Difficulty. Financial Stability Notes, 2024(7), Central Bank of Ireland.

Adhikari, T., and McGeever, N. (2023). How resilient are Irish SMEs to input cost inflation? Financial Stability Notes, 2023(6), Central Bank of Ireland.

Bloom, N. (2009). The Impact of Uncertainty Shocks. Econometrica, Econometric Society, 77(3), 623-685.

Central Bank of Ireland (2023a). Financial Stability Review 2023:I. Central Bank of Ireland.

Central Bank of Ireland (2023b). Financial Stability Review 2023:II. Central Bank of Ireland.

Central Bank of Ireland (2024). Financial Stability Review 2024:I. Central Bank of Ireland.

Central Bank of Ireland (2025a). Financial Stability Review 2025:I. Central Bank of Ireland.

Central Bank of Ireland (2025b). On the fault line? The Irish economy in a time of geoeconomic fragmentation. Signed Article, 2025(3), Central Bank of Ireland.

Department of Finance (2024). Economic Insights. Spring 2024.

Girardi, A., and Reuter, A. (2017). New uncertainty measures for the euro area using survey data. Oxford Economic Papers, 69(1), 278-300.

Lawless, M., O’Connell, B., and O’Toole, C. (2015). SME recovery following a financial crisis: does debt overhang matter? Journal of Financial Stability, 19 (August 2015), 45-59.

Mahony, M., and O’Neill, C. (2025). The drivers of SME investment in Ireland. Staff Insight, 2025(3), Central Bank of Ireland.

McCann, F., and Yao, F. (2021). Simulating business failures through the liquidity and solvency channels: A framework with applications to COVID-19. Research Technical Paper, 2021(2), Central Bank of Ireland.

Appendix

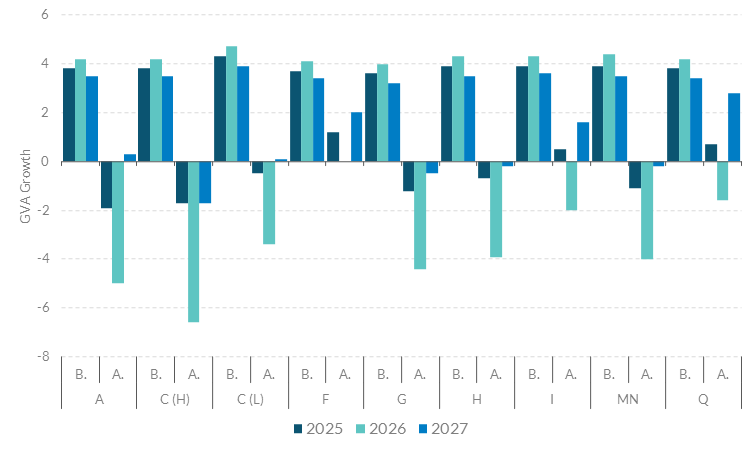

Turnover is shocked using EBA GVA growth by sector

Figure A1: Real GVA growth by sector in the baseline and adverse scenarios

Source: European Banking Authority.

Note: B. refers to baseline and A. to adverse. Industry NACE codes: H (transportation/storage), C (manufacturing), I (accommodation/food), F (construction), A (agriculture), G (wholesale/retail), MN (professional/administrative), and Q (human health/social work).

Accessibility: Get the data in accessible format. (CSV 0.27KB)

Endnotes