Key Insights

Notwithstanding some recent signs of stabilisation, Dublin’s office market has been amongst the hardest hit across Europe in terms of decrease in capital values, fall-off in investment and the rise in vacancy rates since the start of the decade. The extent of the slowdown, however, has not been as sharp as in some large US cities.

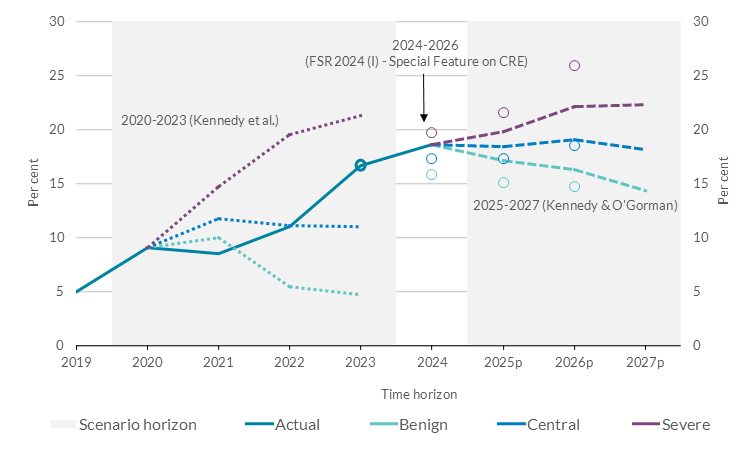

Using an enhanced methodological framework to project short-run vacancy rates, the central scenario for the Dublin office vacancy rate is a marginal rise to just over 19 per cent in 2026 before falling back below end of 2024 levels (18.6 per cent) by the end of 2027.

A scenario based on a more benign set of assumptions suggests that the Dublin office vacancy rate may have already peaked, while the more adverse case sees a return to levels last seen around the time of the Irish property market collapse in 2009. In contrast to the 2009 episode, any further significant increase in office vacancy would occur against a markedly different CRE landscape, where current risks are much less concentrated within the domestic financial system.

Introduction

Why the vacancy rate matters?

The significant downturn in commercial real estate (CRE) markets globally and in Ireland since late 2019, and the financial stability concerns it raises, have been the subject of much recent commentary from the Central Bank of Ireland (the “Central Bank”) and international institutions such as the European Systemic Risk Board (the “ESRB”).[1][2] This Insight examines the challenges facing the Dublin office sector, a market that has experienced a substantial adjustment in capital values this decade, notwithstanding some recent signs of stabilisation[3] as interest rates have eased. Office markets tend to be highly cyclical and internationally synchronised. They are considered, broadly speaking, a good barometer of wider economic health and have the advantage of good data availability with a high degree of cross-country comparability.[4] An area of particular focus is the evolution of the Dublin office vacancy rate, which climbed to well over 18 per cent during 2024.

[5]

Vacancy rates are a key indicator of imbalances between the supply and demand for office units. They rise when the supply of space is outstripping the demand for that space. Dublin office vacancy rates have risen sharply, by 13.5 percentage points since 2020, well above long-run average values, signalling weak occupier demand relative to supply. Elevated aggregate vacancy rates should, all else being equal, reduce future rents as leases expire and new lettings are negotiated. Lower projected income returns in turn may reduce the valuation of Dublin offices, while uncertainty around the future income stream can affect the risk premium demanded by investors to hold an asset. A decrease in collateral values or a reduction in ability to service debts, given lower income can affect lenders’ asset quality on CRE books.

[6] Constructing scenarios for future vacancy rates can, therefore, support financial stability risk assessments and complement wider market and lending analytics.

To examine the Dublin office market vacancy rate, we update the framework first introduced in Kennedy et. al. (2021) (PDF 698.89KB).[7] Specifically, the initial framework was based on a scenario analysis, encompassing a range of the key drivers of office occupancy such as:

- the development pipeline,

- future take-up,

- rates of working from home (WFH) and,

- changes to the post-COVID office space per employee ratio[8],

This framework is now enhanced with new information from granular commercial lease register data, collected by the Property Services Regulatory Authority (PSRA). To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first such use of these data. Under a range of assumptions, the updated central scenario for the Dublin office vacancy rate is a relatively marginal rise to just over 19 per cent in 2026 before falling back below current levels by the end of the time horizon considered, in 2027. Two additional scenarios, one based on a more benign set of assumptions and another encompassing more severe outcomes, complete the analysis.

Developments in the Dublin office market since 2020

Capital values and rents

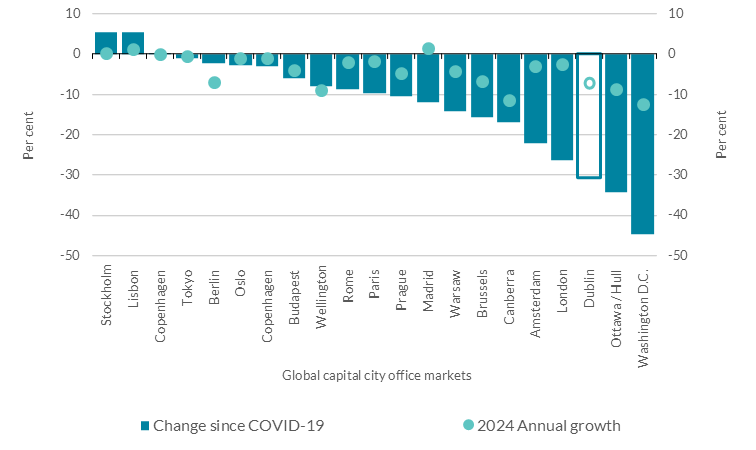

Dublin office capital values have declined significantly this decade, (by more than 30 per cent from pre-COVID peak), given structural issues, (increased levels of remote working), and cyclical factors (tightening of global monetary policy during 2022 and 2023). Globally, many office markets have followed a similar trajectory over the same period: a consequence of similar challenges and a deep, globalised pool of investment capital in office markets. Cities such as Amsterdam, London, Ottawa and Washington D.C., for example, have experienced significant cumulative falls of between 20 and 45 per cent in office capital values post-2019 (Figure 1).

Office markets across the world, including Dublin, have experienced significant falls in recent years

Figure 1: Office market capital value growth across select capital cities

Source: MSCI

Note: Change since COVID-19, measures the cumulative change in MSCI capital value (office) indices across a selection of global capital cities over the period 2019Q4 to 2024Q4. Latest observation 2024 for all locations except Wellington where latest observation is from 2023.

Accessibility: Get the data in accessible format. (CSV 1.73KB)

Dublin office rents in contrast, have been relatively stable, falling by about 2 per cent during the same period. A combination of solid domestic economic growth, and a significant share of existing lengthy rental agreements, from before the pandemic, have likely contributed to this moderate adjustment in market rents. Moreover, market intelligence indicates that inducements to occupiers, such as rent-free periods or the covering of fit-out/re-purposing costs are offered as alternatives to rent reductions, thus avoiding the capitalisation adjustments that would ensue from reductions in headline rents. Recent survey data also point to the provision of comparatively significant average discounts via rent-free periods (compared to the total lease value) for prime and secondary Irish offices in recent years.[9] As leases from the pre-2020 period continue to expire and come up for renewal, uncertainty surrounding the post-pandemic “steady state” demand for space, means further downward adjustments in Dublin office rents are possible.

Investment expenditure and take-up

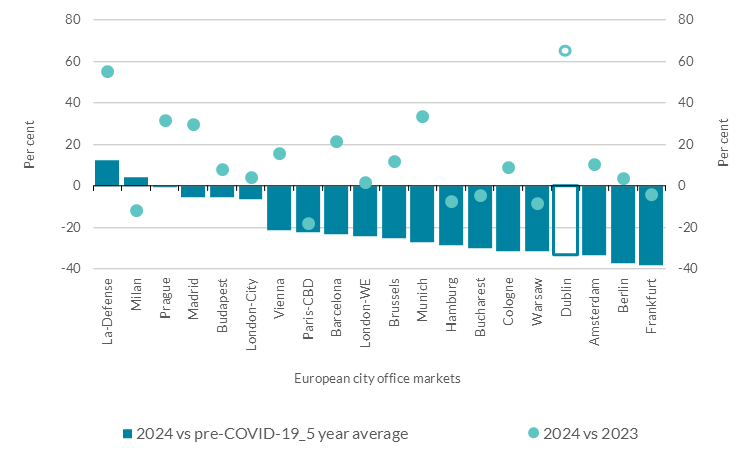

As noted in the Special Feature “Commercial Real Estate: A Macro-Financial Assessment” (2024), investment in the Irish office sector has declined sharply in recent years[10] amid rising funding costs and a deterioration in both investor appetite and occupier demand for office units.[11] Following a very sluggish 2023, where the take-up of Dublin office space was the lowest since 2010, there was some rebound in letting activity during 2024, where approximately 210,000 square metres was occupied, in line with the long-run (2003-2024) average annual take-up, albeit about one third lower than in the years prior to the emergence of COVID-19. While recent office-leasing activity seems similarly depressed across several major European cities in comparison to pre-COVID levels, Dublin appears to have been one of the locations hit hardest, notwithstanding the pick-up observed during 2024 (Figure 2). A reduction in letting activity from the tech sector , following a bout of restructuring and downsizing in many firms, has been an important contributory factor in this regard.[12]

Dublin offices have also seen a comparatively significant decline in leasing activity relative to pre-COVID-19 levels

Figure 2: Change in the volume of European office space leased

Source: Savills (European office outlook)

Note: Data are a comparison between the volume of office space (in square metres ) leased during 2024 relative to (i) the total for 2023 and (ii) pre-COVID 5-year average annual Dublin office lettings (i.e. between 2015 to 2019). Latest observation 2024.

Accessibility: Get the data in accessible format. (CSV 1.95KB)

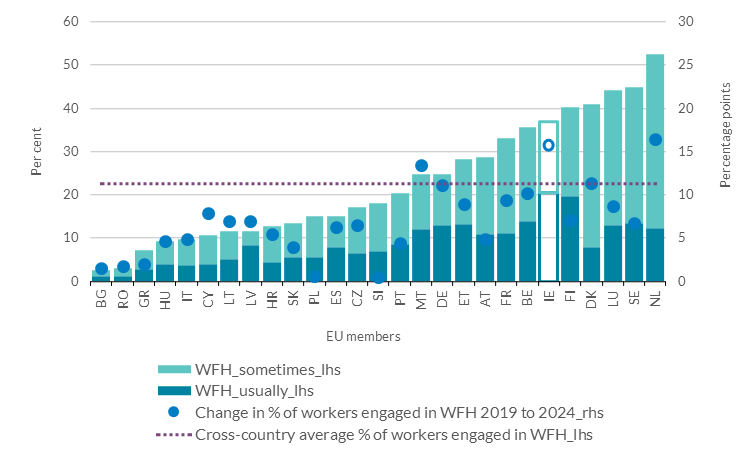

The more pronounced shift towards remote working in Ireland is also likely to have had a negative impact on leasing activity (Figure 3). An update of Eurostat figures for 2024, show that Ireland continues to have one of the largest cohorts of its workforce “usually” working from home (20.6 per cent) and after the Netherlands, has experienced the largest increase (15.7 percentage points) of any EU country in the share of employees who “usually” or “sometimes” work from home since the pandemic (36.8 per cent in total).[13] Moreover, Barrero et al. (2023)[14] show how the sectors with the highest rates of WFH in the US (such as ICT, finance and professional services) are those the Dublin office market has a particularly high exposure to in terms of leasing activity[15] and employment. O’Sullivan and McGuckin (2024)[16] note however, that the potential for future growth and expansion within these sectors remains high, which could help mitigate some of the negative impact of remote working on take-up over time.

Ireland has been one of the highest adopters of remote working amongst European peers

Figure 3: Employed persons working from home as a percentage of total employment

Source: Eurostat

Note: Workers engaged in WFH as per chart includes individuals who WFH both usually and sometimes. Latest observation 2024.

Accessibility: Get the data in accessible format. (CSV 1.08KB)

Vacancy rates

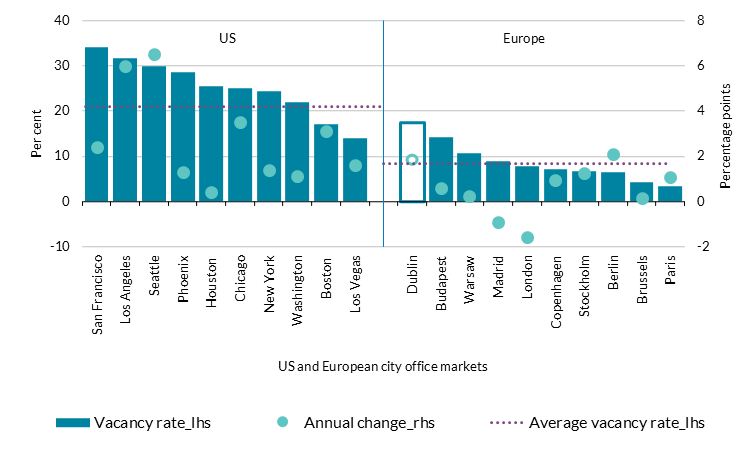

The marked increase in unoccupied office space, against the backdrop of pronounced changes to working patterns over the past 5 years has taken the office vacancy rate in the Irish capital (18.6 per cent)[17] to well above its long-run (2003-2024) historical average of 13.7 per cent, as well as the current average across a sample of European markets (Figure 4). The present vacancy rate is also well above the Dublin office market’s “natural vacancy rate”, the point where the market is in equilibrium and there is neither an excess in supply nor demand for rental space. This tipping point between positive and negative rental growth is estimated to be around 11 per cent across a range of sources.[18] A prominent feature of the data is that recent increases in office vacancy rates appear to have been greater across many US cities than in Europe (Figure 4).

Dublin office vacancy rate is high relative to elsewhere in Europe, but lower than in many US cities

Figure 4: Office market vacancy rates in select European and US cities (2024)

Source: European data from Savills (European office outlook - December 2024) and US data from Cushman & Wakefield (US national market beat - office Q4 2024).

Note: Annual change refers to the percentage point difference between the 2023 and 2024 vacancy rates. Average figures refer to wider sample of European and US cities. Latest observations 2024.

Accessibility: Get the data in accessible format. (CSV 1.59KB)

Looking ahead, a key driver of Dublin’s office vacancy rate in the near-to-medium term will be the extent to which the market can absorb the volume of new and/or refurbished office space coming on-stream. Projections of the near-term construction pipeline are indicative of a supply response from office developers. CBRE data suggest that the volume of new space, either granted planning or already under construction, and due for delivery during the period 2025 to 2027, has declined from about 370,000 square metres at the end of 2023, to approximately 190,000 square metres at the close of 2024. The latter figure equates to a little less than 1 year’s average annual Dublin office take-up. Even this lower additional supply however, about half of which was pre-let at the end of last year, could depress prices further if a significant amount of the un-let space remains unoccupied, given the already elevated level of vacancy.

Scenario analysis - Dublin office vacancy rate

A framework for considering the impact of structural changes

To complement the broader assessment of risks and vulnerabilities facing Dublin offices, a framework for examining the potential impact of changes to key factors likely to influence the office vacancy rate in Dublin was developed and featured initially in Kennedy et al. (PDF 698.89KB) (2021). In this section, details of the enhancements made to this methodology are provided, before the findings of an updated scenario analysis, covering the period 2025-27 are discussed.

The outcome of the individual scenarios will be influenced by the different assumptions made to the key determinants of vacancy, i.e., the supply pipeline and future take-up, the rate of lease expiration and renewal, levels of WFH, and post-pandemic changes to office layouts and space per employee ratio (see Table 1). In recognition of the likelihood that recent structural changes may take some time to be fully reflected in market dynamics, not to mention elevated economic and geopolitical uncertainty and the potential adverse implications of abrupt shifts to US trade and tariff policies, three scenarios (central, benign and severe) with differing assumptions are set out.

To the extent possible, the assumptions underpinning the scenario analysis are grounded in real world observations and data. The Dublin office market is sensitive to swings in investor sentiment and occupier demand. Persistent uncertainty with respect to the international trading environment may impact decisions of large MNCs, such as those in the tech, pharma or financial services sectors, firms that have leased significant portions of Dublin office space recent years. A negative impact on the volume of trade or employment, could see firms abandon or defer expansion plans, reducing occupier demand and leading to an increased vacancy rate, with knock-on implications for capital values and rents.

Table 1: Data sources and assumptions for Dublin office vacancy rate scenario analysis

| | Source | End-2024 |

| Existing space | AIB & CBRE | Total Space: 4.3m sq. metres Occupied Space: 3.5m sq. metres (81.4% occupancy) Vacant Space: 800k sq. metres (18.6% vacancy) |

| | | | Central | Benign | Adverse |

Assumption 1: New space & take-up | CBRE | Forecast delivery (2025-27) 2025 (60,000 sq.m) 2026 (40,000 sq.m) 2027 (90,000 sq.m) | Take-up 70% p.a. | Take-up 90% p.a. | Take-up 50% p.a. |

Assumption 2: Lease expiry | PSRA | Lease expiration p.a. % | 2025 (7.9) 2026 (11.6) 2027 (4.5) | 10% lower 2025 (7.1) 2026 (10.4) 2027 (4.1) | 10% higher 2025 (8.7) 2026 (12.8) 2027 (5.0) |

Assumption 3: WFH | Survey Data (NUIG, Barrero et. al., Colliers/Corenet & CSO/Eurostat) | Surplus space - due to lease expiration & increased WFH (relative to situation pre-pandemic) | 30% of the space subject to lease expiration p.a. | 20% of the space subject to lease expiration p.a. | 40% of the space subject to lease expiration p.a. |

| Assumption 4: Repurposing of space | | Increase in office space per employee ratio | 1 sq.m | 1.25 sq.m | 0.75 sq.m |

Data sources and assumptions

Assumption 1: Existing Dublin office space and new completions

The Dublin office market is estimated to consist of approximately 4.3 million square metres at the end of 2024.[19] Of this, approximately 800,000 square metres or 18.6 per cent of the available space lies vacant.

The first assumption relates to the volume of scheduled office completions in Dublin over the forecast horizon, 2025-27, and the subsequent take-up of space. CBRE produce regular statistics detailing potential new office supply for Dublin. Estimates from late 2024 suggested that approximately 190,000 square metres of additional office stock would be delivered to the city by the end of 2027, with 60,000, 40,000 and 90,000 square metres due to come on-stream during 2025, 2026 and 2027 respectively, (see “Assumption 1”, Table 1). At the time of these estimates, about half of this new space is pre-let,[20] with the remaining portion still vacant. The assumption underlying the “central” scenario is that given the heightened uncertainty at present, about 70 per cent of the total new Dublin office stock coming on-stream between 2025 and 2027 will be occupied within that time frame. Under more benign conditions this figure rises to 90 per cent, while the more severe outcome assumes that the take-up of new office space does not move much from its current level of around 50 per cent. A depreciation rate of 1.5 per cent of outstanding stock per annum is also assumed across the board. These initial assumptions are broadly in-line with those set out originally in Kennedy et al. (PDF 698.89KB) (2021).

Assumption 2: Commercial leases

Our analysis indicates that about one quarter of leased Dublin office space will expire and come up for renewal at some stage over the 2025-27 period.[21] This finding is predicated on an examination of the Property Services Regulatory Authority’s (PSRA’s) Commercial Lease Register[22], the first such use of these data in this manner to the authors’ knowledge.[23] A dataset, consisting of Dublin office leases entered into during the period 2012 to 2024, including details of lease commencement date, contract duration and annual rent payable is constructed. The result is a sample of approximately 6,900 observations.[24] By combining annual rent payable figures across leases from the sample with MSCI data on average Dublin office rents per square metre for the corresponding year it is possible to estimate the volume of office space accounted for by each lease, and thus the aggregate volume of space leased, and subject to lease expiration in a particular year.[25] To account for any gaps in the CRE lease register data, lower / higher expiration rates of 10 percentage points are assumed in the respective more benign / and adverse scenarios (see “Assumption 2, Table 1).

Assumption 3: Working from home arrangements

Demand for office space has been severely affected by changing working practices post-COVID-19. As seen in Figure 3, Ireland has a relatively high share of its workforce engaged in remote working, at least to some extent. While policies differ markedly across firms and locations, and a high degree of uncertainty remains as to where the “steady state” ultimately settles, survey data and studies by NUIG[26], Barrero et al.[27],, or Colliers/Corenet Global[28], are useful additions to the WFH statistics gathered by the CSO and Eurostat. Despite some methodological differences across studies and surveys, there appears to be a degree of consensus on the level of remote working occurring at present.[29]

The central scenario assumes that about 30 per cent of the leased space up for renewal over the next few years may be surplus to the requirements of the existing occupiers due to increased levels of WFH relative to pre-pandemic norms. This increases to 40 per cent under the more severe scenario, and falls back a little to 20 per cent, under more benign conditions where firms’ preference is for employees to spend more time on-site.

Assumption 4: Office space per-employee ratio / repurposing of space

The final assumption attempts to account for changes in the office space per employee ratio, arising from modified occupier preferences with respect to office layouts in a hybrid-working environment. McCartney (2024), notes that the occupational density ratio for recently hired office workers has fallen substantially, from 10.2 to 3.2 square metres per employee post-COVID, due to increased adoption of WFH. In response, office lessors have been offering to repurpose / improve existing facilities as an incentive to occupiers, through for instance the addition of more meeting rooms, collaboration spaces, training rooms, canteens, changing rooms etc.

To reflect this, an increase in the typical volume of space consumed per office worker is assumed.[30] Under the central scenario, the average space allotted to office workers, (affected by lease renewal negotiations), increases by an additional square metre. In the severe scenario, the space per employee ratio increases by just 0.75 square meters, while the more benign scenario sees it rise a little to 1.25 square metres per worker.

Key findings

How might vacancy rates evolve?

The outcome of the updated framework and three scenarios for the near-term path of Dublin office vacancy rates are presented in Figure 5. Also included are the findings from the initial exercise in 2021, where the actual vacancy rate tracked ultimately between the central and adverse scenarios. So too, are the results of an earlier revision of the framework for the Special Feature “Commercial Real Estate: A Macro-Financial Assessment” (2024) where the outcomes of the severe and benign scenarios were a little more dispersed, due to the use of earlier assumptions on the delivery of new office stock and comparatively higher lease expiration during 2024.

Under the refreshed central scenario, the vacancy rate dips slightly during 2025 (to 18.4 per cent), as the portion of unoccupied new space, plus vacant stock (post-lease expiration) is more than offset by the repurposing of office accommodation. Increased space per worker in the following year is not enough to offset the higher rate of lease expiration, leading to an increase in the vacancy rate in 2026 (to 19.1 per cent). The reverse occurs during the final year under review, despite an increase in the expected volume of new supply. The additional supply and a drop off in supplementary space due to lease expiration is more than outweighed by the additional office space required for the provision of enhanced facilities, resulting in a fall back in the vacancy rate to 18.2 per cent by 2027.

Under the central scenario, the Dublin office vacancy rate drops below its 2024 level by 2027

Figure 5: Dublin office vacancy rate projections (2021-23, 2024-26 and 2025-27) under central, benign and severe scenarios

Source: Authors’ calculations.

Note: Shaded areas and dashed lines refer to the 2021-23 and 2025-27 exercises, with dots referring to 2024-26 projections from the Special Feature “Commercial Real Estate: A Macro-Financial Assessment” (2024)

Accessibility: Get the data in accessible format. (CSV 1KB)

The “benign” scenario suggests the Dublin office vacancy rate may have already peaked, as it eases back towards 17 per cent in 2025, records another slight improvement and drops to 16.3 per cent in 2026, before a further decline to 14.4 per cent by the end of 2027. In this case, the less severe assumptions related to the expiration of leases and change in WFH rates from before the pandemic are the main reasons for the lower vacancy rates, followed by the assumption that a higher share of new completions is ultimately let. The additional space per employee plays a relatively smaller role in terms of the difference with the central scenario.

In contrast, the more severe scenario would see a significant increase in the vacancy rate as the alterations to office layouts are not nearly enough to offset the excess vacant space arising from the greater degree of remote working that is assumed. The Dublin office vacancy rate approaches 20 per cent by the end of this year and subsequently rises to 22.3 per cent by the end of the forecast horizon in 2027. Were it to unfold, this scenario would place the Dublin office vacancy rate about 1 percentage point below its level at the time of the Irish property market collapse of 2009 to 2011. One would expect, all other things equal, that such an elevated vacancy rate would be associated with further sharp declines in capital values. Given the extent of the decline that has already occurred however (more than 30 per cent from pre-COVID peak), it is difficult to envisage how events would unfold were this scenario to transpire.

Conclusion

Given their size and systemic interlinkages to the real economy and wider financial system, CRE markets are important to monitor as a potential source of financial instability. This has been brought into even sharper focus given the significant headwinds faced by the sector globally and in Ireland in recent years, arising from a significant increase in interest rates, in addition to changed post-COVID working practices. The Dublin office market has experienced one of the more significant slowdowns in Europe, though some large US cities have witnessed even greater falls.

This Insight uses a scenario analysis approach to assess the possible evolution of office vacancy rates in the Dublin market over the coming years. In our central scenario the Dublin office vacancy rate would see a relatively marginal rise to just over 19 per cent in 2026 before falling back towards 18 per cent in 2027. A more benign scenario suggests the vacancy rate may have already peaked. Were events to track closer to the severe assumptions the vacancy rate could increase significantly over the next few years, leaving more than one fifth of Dublin’s office stock vacant by the end of 2027.

From a financial stability perspective, any further deterioration in the Dublin office market should be placed in the broader context of a resilient financial system in Ireland. It is also important to acknowledge, as laid out in Special Feature “Commercial Real Estate: A Macro-Financial Assessment” (2024), the marked changes which have occurred in the Irish commercial property landscape since the GFC, where activity is widely diversified and risks much less concentrated within the domestic financial system.

A return to a more stable and certain international environment could boost confidence, strengthening the nascent recovery in the domestic CRE market that appears to have emerged during 2025, leading to increased letting activity and a sustained reduction in the Dublin office vacancy rate over the near-to-medium term. Our scenario analysis is an effort to provide market participants with a plausible range of future outcomes, facilitating discussion, planning and investment.

Endnotes

- Macro-Financial Division, contact Gerard Kennedy. Cillian O’Gorman is also affiliated with University College Dublin and participated in this research project while working as an intern at the Central Bank of Ireland. Thanks to Niamh Hallissey, Maria Woods, Angelos Athanasopoulos, Fergal McCann, Barra McCarthy, Philip Dempsey and Conor Kavanagh for helpful comments on an earlier draft. All views expressed in this Insight are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily represent the views of Central Bank of Ireland. ↑

- See Financial Stability Review 2024:II (PDF 1.81MB) and Financial Stability Review 2024:I - Special Feature “Commercial Real Estate: A Macro-Financial Assessment” (PDF 796.22KB) (Central Bank of Ireland, June and December 2024) and “Vulnerabilities in the EEA Commercial Real Estate Sector” (ESRB, January 2023) for more details. ↑

- See, Financial Stability Review 2025:II, Central Bank of Ireland (November 2025). ↑

- Shaikh (2024) showed that the Dublin office sector, with an estimated worth of around €25 billion, was the second largest block (by value) within the broader Irish commercial property market, which he valued at approximated €144 billion. See “Estimating the total value of Ireland’s commercial property stock (PDF 584.34KB)”, Central Bank of Ireland, Financial Stability Note, Vol. 2024, No.3. for more details. ↑

- See, Dublin Office Market Q4 2024, CBRE (January 2025) for more details. ↑

- See Special Feature “Commercial Real Estate: A Macro-Financial Assessment” (PDF 796.22KB) (Central Bank of Ireland, June and December 2024) for more details. ↑

- See “COVID-19 and the commercial real estate market in Ireland”, Central Bank of Ireland, Financial Stability Note, Vol. 2021, No.4. for more details. ↑

- According to McCartney (2024), the typical amount of office space consumed by an office worker has fallen from 10.2 square metres per employee pre-2019, to 3.2 square metres per employee since 2020. See “The office market is in a downswing that is unlikely to be especially deep – but it could prove to be a long one”, Irish Independent, March 2024, for more details. ↑

- See RICS Global Commercial Property Monitor for more details. According to data from 2024Q3 survey, Ireland ranks towards the upper end of a selection of countries in terms of the typical average discount offered to prime/secondary office tenants through rent-free periods. The Irish figures are 10 per cent (prime) and 13 per cent (secondary), compared to series cross-country averages of 7 and 10 per cent respectively and respective max figures of 20 and 22 per cent. More recent survey evidence from 2024Q4, reports that the latest value of the “Inducements – Net Balance” Index for Irish offices is “26”, its 20th consecutive quarter with a positive value, with the current reading well-above the series’ average value of “17”, calculated across a set of quarterly observations beginning in 2008. ↑

- Despite registering a 30 per cent increase to just over €500 million, the volume of office investment during 2024 was still less than 15 per cent of the 2019 figure, and less than 40 per cent of the 2012-2024 annual average. ↑

- According to CBRE Research, Dublin office demand requirements at the end of 2024 amounted to approximately 200,000 square metres, or the equivalent of about one-year’s average annual take-up of Dublin office space (over the period 2003 to 2024). The current figures remain well down however on pre-COVID office demand estimates which were well in excess of 430,000 square metres. ↑

- See “A different kind of property crash hits Dublin as big tech cuts”, Bloomberg, April 2024, for more details. ↑

- It is important to note that these figures represent the entire work force, rather than office workers only and so differ significantly from alternative “working from home” data sources, which focus more on office workers such as those discussed in the Assumptions section. ↑

- See Barrero. J. M., N. Bloom, and S. J. Davis, (2023), “The evolution of working from home”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 37 (4): 23–50), for more details. ↑

- According to data from Lisney Estate Agents, between them, tech, financial and professional services firms were responsible for renting almost 70 per cent of all the Dublin office space leased during the last 10 years. ↑

- See O’Sullivan. P., and R. McGuckin, (April 2024), “The Irish office market: Back to the office, but not as we know it”, AIB Real Estate Finance, for more details. ↑

- CBRE data from end-2024 put the Dublin office vacancy rate at 18.6 per cent (see Dublin office market report Q4 2024 for more details). It’s important to note however, that this figure includes an estimated 220,000 square metres of “grey-space”, that is, a portion of office accommodation which exceeds the current needs of a particular tenant in a scenario where the lease term has not expired. The exclusion of “grey-space” would see the current “true” vacancy rate fall back towards the long-run average vacancy rate. ↑

- See “Dublin office market 2023Q4”, BNP Paribas Real Estate for more details, and reference to the work of Sanderson. B., K. Farrelly and C. Thoday., (2006) “Natural vacancy rates in global office markets”, Journal of Property Investment and Finance, Vol. 24(6), which found that the Dublin office market had the second highest natural vacancy rate (10.9 per cent) of 12 European locations. This compares to the findings of McCartney. J., (2012), “Short and long-run rent adjustment in the Dublin office market”, Journal of Property Research, Vol. 29(3), who estimated a NVR for Dublin of 11 per cent. ↑

- According to Statista, the office market in Dublin is the eighth smallest of 21 European capitals for which data are available, with the volume of space in Ireland’s capital equating to 55 per cent of the sample average and about one-fifth the size of some of Europe’s largest markets, such as Berlin and Paris. ↑

- The breakdown in the volume of pre-let space differs from year to year. Approximately 45 per cent of new space projected to be delivered during 2025 is pre-let; just over one fifth of the 2026 inventory is accounted for, while about one third of the new completions due in 2027 had a tenant lined up at the end of last year. ↑

- The annual breakdown is 7.9%, 11.6% and 4.5% of the capital’s leased office space across 2025, 2026 and 2027 respectively. It is interesting to note that these figures are not too dissimilar to those used in the original analysis of Kennedy et. al. (2021), based on Hayes’ (2020) study measuring the expiration of public sector leases. According to that study, approximately 29 per cent of OPW leases were expected to come up for renewal over the 3-year forecast horizon examined in Kennedy et. al., broken down as follows, 2021 (11.2%), 2022 (12.2%) and 2023 (5.4%). ↑

- Since 2010, the PSRA has been collecting detailed information on CRE rental agreements in Ireland, including property address, type, date of lease commencement, date of lease expiration, and annual rent payable. Due to small sample sizes in the initial years, the analysis in this study concerns leases entered into from 2012. Additional cleaning omits unrealistic or ambiguous values, in cases where lease length is unclear for instance. ↑

- In contrast, assumptions related to office lease expiration in Kennedy et al. (PDF 698.89KB) (2021) were based on the findings of Hayes’ (2020) review of public sector leases. ↑

- See Special Feature “Commercial Real Estate: A Macro-Financial Assessment (PDF 796.22KB)” (2024), for some initial summary statistics, including findings on average and typical lease lengths. ↑

- One shortcoming of the PSRA data is the inability to identify leased space which has been sublet, which may introduce an element of double counting. While the volume of sublet “grey” space, i.e. accommodation that is leased by a tenant but surplus to their current requirements, has increased notably in recent years, in the context of the overall market, it is believed to account for a relatively small portion of leasing activity. ↑

- See NUIG/WDC, National Remote Working Survey for more details. ↑

- See WFH Research Survey of Working Arrangements and Attitudes for more details. ↑

- See Hybrid Work: A Look Forward for more details. ↑

- The WFH categories used consist of, “Always” (5 days/week), “Usually” (3 to 4 days/week), “Sometimes” (1 to 2 days/week), “Occasionally” (a couple of days/month) and “Never” (0 days per week/month), and how the share of workers within these groups has changed between the pre, and post-COVID environment. Post-pandemic WFH figures are based on the difference between the level of remote working pre-COVID-19, and the more recent updated figures based on the survey data considered here. In addition, it is important to note that the rise in WFH will only affect the space covered by the leases that are expiring / up for renewal (see “Assumption 2”) and so the WFH figures are only applied to this segment of the market. Where leases are not up for renewal, WFH plans and any potential impact on the vacancy rate are not considered since they are tied to an existing lease. ↑

- Using a methodology similar to Savills 2016, it is estimated that around 430,000 individuals were engaged in Dublin office based work at the end of 2024. ↑