What’s happened to consumption?

22 July 2020

Blog

Consumption is a fundamental component of economic activity. Decisions that households make on the type of goods and services they wish to purchase will determine the products that firms will decide to produce. Firms have to consider how consumers will behave when preparing their future business plans which will involve a number of factors, not just what consumers may wish to buy but also what they will be able to buy.

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a severe downturn for the Irish economy (and for economies around the world). Declines in consumption are an expected feature of economic downturns, not least because individuals spend less due to a loss of income. Today’s crisis is unusual in that households have not had a choice even where they have not had a loss of income. They have been unable to consume goods and services as they normally would as a result of the restrictions imposed for health reasons.

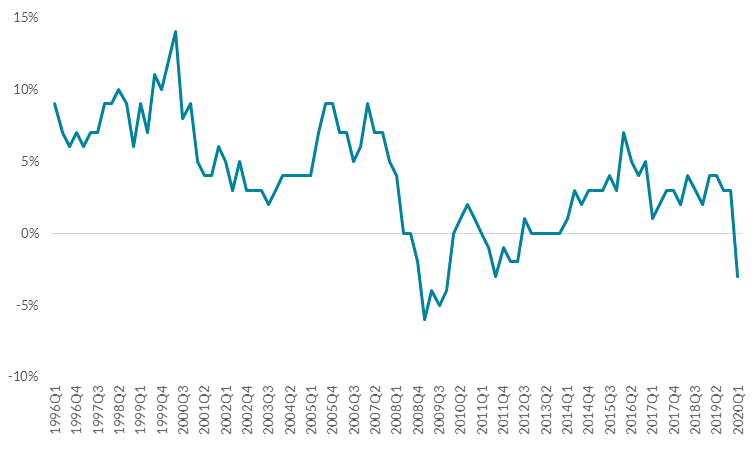

Figure 1: Consumption Growth Ireland

Source: CSO

Of course, consumers may also willingly be spending less due to the high degree of uncertainty around both their incomes and potential risks to their own health. More than half of respondents to a recent CSO survey reported they were very or extremely concerned about somebody else’s health. More than half of respondents to the same survey also expressed high levels of discomfort about engaging in various types of economic activity such as shopping, eating and drinking out, going on public transport and domestic/foreign travel. Illustrating just how intertwined the health and economic outcomes are, those with the highest levels of discomfort also tend to be less likely to have seen their income fall as a result of the crisis. For example, older respondents are the most uncomfortable engaging in economic activity, but they are also the group least likely to have experienced a fall income since March.

We are also seeing upheaval in how we work, shop, and how we live as some pre-crisis trends have accelerated due to COVID-19. For example, businesses have seen a greater proportion of their sales coming from online sources. How these trends evolve as we emerge from the current crisis will have important effects on our society and economy.

Income supports provided by the Irish government are a key element to consider here. The effectiveness of the policy can be seen in CSO survey data: around 70% of respondents reported no change in their net income since the introduction of COVID-19 restrictions and around 80% reported reduced expenditure (as we would expect).

This fall in expenditure combined with relatively stable incomes has resulted in an increase in savings for consumers. (Payment breaks provided by the financial system will also have helped households to maintain liquidity during this period.)

Increases in household deposits

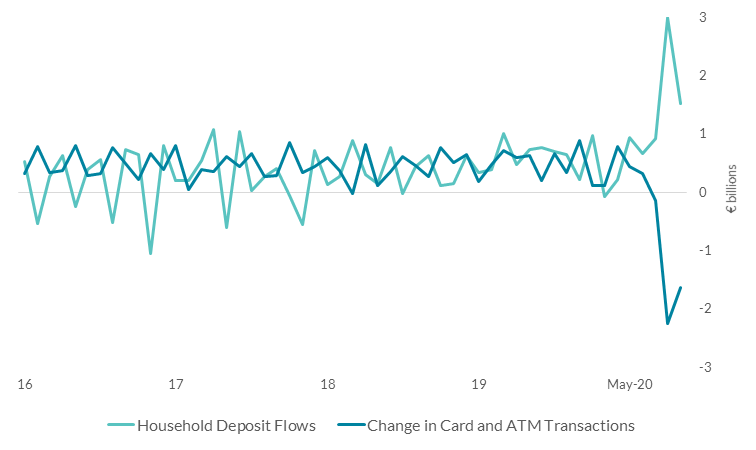

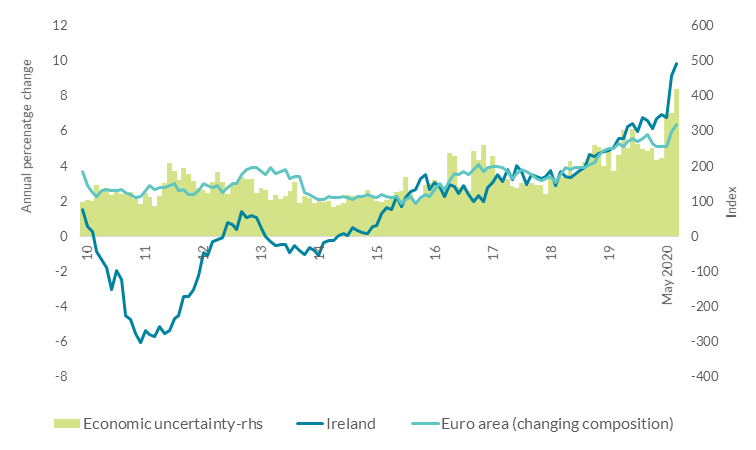

Last week, we published some detailed analysis of how household deposits have behaved through the current pandemic. Deposits have increased sharply since the crisis started (see Figure 2). Although the recent exceptional increase may be linked to limited spending opportunities and stable income (due to COVID-related supports), the growth in deposits has been evident since mid-2018, for both Irish and Euro area households. This could be driven by a number of factors, but increased economic uncertainty leading to precautionary savings may also be a factor. Figure 3 shows this increased deposit growth and also outlines how economic uncertainty has increased in recent years, due to the withdrawal of the UK from the EU and rising geopolitical trade disputes. Given these uncertainties, households may have been saving to provide protection against potential shocks.

Figure 2: Exceptional monthly deposit growth in April 2020 coinciding with lower spending activity

Source: Central Bank of Ireland calculations.

Note: ‘Card and ATM Transactions’ is calculated as the difference between total card and ATM transactions in a given month and the same month of the previous year.

Figure 3: Irish deposit growth surpass European growth since mid-2019 with exceptional growth in the year to May 2020.

Source: Central Bank of Ireland, ECB and Davis, (2016).

Note: Global economic uncertainty index (Davis, 2016, “An Index of Global Economic Policy Uncertainty”, Macroeconomic Review, October.

The macroeconomic implications

Our recent Quarterly Bulletin (PDF 1.16MB) discusses the macroeconomic implications of increased savings by households. As I’ve mentioned, part of this increase can be considered ‘involuntary’ savings due to consumers’ reduced ability to spend. How these savings are used will be important in the recovery from the current downturn. John FitzGerald also discussed this recently and provided an interesting historical comparison of how Irish consumption rebounded sharply after the Second World War. After the war ended, there was a significant increase in the consumption of previously unavailable goods as households, instead of continuing to save, used their savings for consumption.

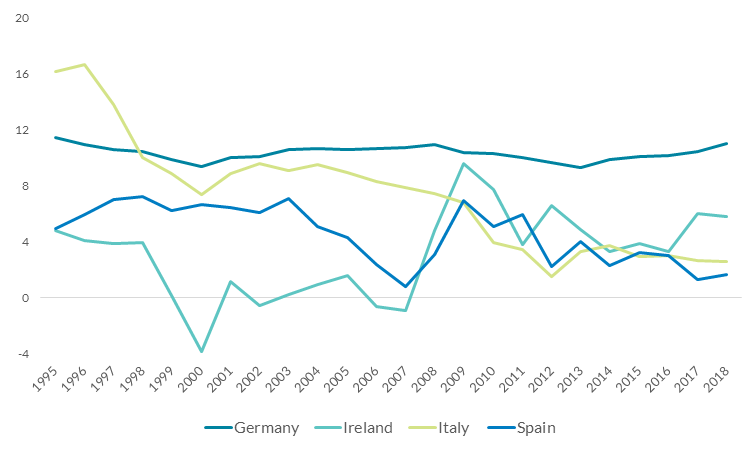

Figure 4 shows Ireland’s household savings rate in comparison to some other European countries over the past twenty years or so. There are of course a number of factors behind these patterns but the low and even sometimes negative rate for Ireland is notable in the years before the last crisis. We can see that the savings rate was in a healthier position entering the current crisis.

Figure 4: Household savings rates

Source: OECD

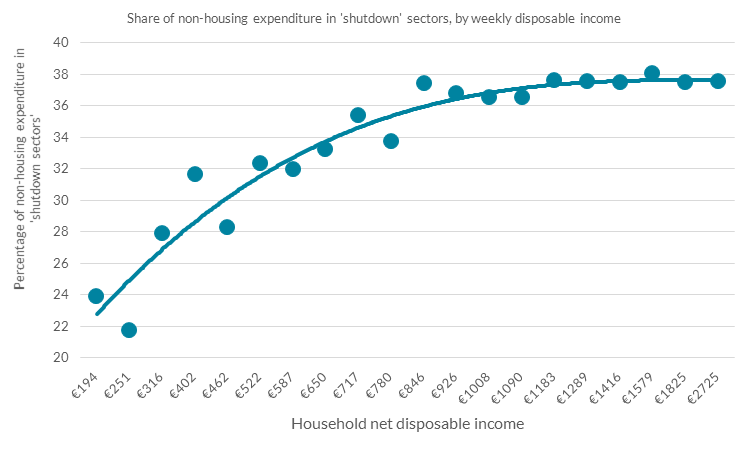

A key question is what consumers will do with the savings that are currently being built-up. One thing to bear in mind is that the scale of these ‘involuntary’ savings is likely to be different across households, simply because the share of spending in shutdown sectors is not the same for everyone. Figure 5 shows that for highest income households, the share of spending in ‘shutdown’ sectors (38%) is far greater than for lower income households (22%). Similar patterns are reported in the UK and Spain, suggesting that higher income households are likely to have increased their savings by more during lockdown. The qualitative evidence in the CSO Social Impact Survey, which shows more “very affluent” individuals reducing their expenditure compared to “disadvantaged” individuals despite similar income shocks, is also in-line with what we would expect based on pre-Covid spending patterns.

Evidence (PDF 1.07MB) from household wealth surveys, which shows that wealthier households tend to spend less of their savings, suggests that these differences could matter for spending as restrictions ease. Again, the qualitative information in the CSO Social Impact Survey supports this: when asked what they plan to do with involuntary savings, the most “affluent” individuals are more likely to say they will save it (62 per cent, compared with 42-46 per cent of “disadvantaged” individuals).

Figure 5: Share of spending (pre-Covid 19) in ‘shutdown’ sectors by income

Source: Household Budget Survey 2015/16. The x-axis shows household net disposable income by quantile. The y-axis shows the share of total weekly spend in ‘severe’ spending categories, as set out in Quarterly Bulletin 2, 2020, Figure 2 (PDF 881.23KB). Spending on housing (rent and mortgages) is omitted. ‘Severe-social’ consists of restaurants, recreation and culture, alcohol, hotels and transport services; ‘severe-other’ consists of vehicles, clothing and footwear, furniture, personal care and other personal spending. The line in the chart is a fitted polynomial (order = 3) to the data (R-squared=0.93).

‘Involuntary’ savings are just one part of the picture when looking at the coincidence of lock-down measures and deposit increases. Precautionary behaviour in the face of (expected) income shocks, increased job insecurity, or related to health concerns will also influence savings. If consumers decide to save more, then this will have the benefit of increasing personal and household resilience. But if the savings rate becomes excessively high across the economy, there is a risk that the reduced aggregate consumption will result in a drag on economic growth. We saw this (PDF 3.6MB) during the financial crisis – albeit in a different way – when weak household balance sheets interacted with negative income shocks, leading to a drag on consumer spending. Weaker economic growth could then result in a less resilient economy, with fewer opportunities for individuals and households.

Alternatively, if conditions improve and consumers feel more confident and secure in their future prospects – both economically and health-wise – we might avoid a prolonged increase in precautionary savings, and see a greater release of the pool of ‘involuntary’ savings, all of which would provide a significant boost to consumption in the future. Policymakers will need to monitor this. If these savings did turn out to represent a certain degree of pent-up demand, any future policy decisions would need to factor in a potentially significant increase in consumption for the economy. On the other hand, if precautionary saving turns out to be the more important consideration for consumers, policymakers may need to consider ways to mobilise these deposits.

Conclusion

The current uncertainty means it is too early to tell what will happen to consumption over the next 12 months. Policymakers cannot, of course, simply make consumers feel confident. I suggest short-term consumer sentiment will depend most of all on the ability of health systems to handle the virus (whether through the discovery of a vaccine or through an increase in capacity/ability to manage its impact). And in view of the importance of consumption to overall economic activity, it’s probably never been truer that good health policy – and the strengthening of our human capital – is good economic policy.

Gabriel Makhlouf

Read more