Monetary policy, regulation and inequality: a tale of inter-linkages - Remarks by Governor Makhlouf at Social Justice Ireland

16 November 2022

Speech

Speech at Social Justice Ireland by Gabriel Makhlouf, Governor of the Central Bank of Ireland and Member of the Governing Council of the ECB

Good afternoon. It is a pleasure to be here today. I want to take this opportunity to talk about the Central Bank’s mission ‘to maintain monetary and financial stability while ensuring that the financial system operates in the

best interests of consumers and the wider economy’, and the importance of inequality in our considerations.

The title of my remarks today is ‘Monetary policy, regulation and inequality: a tale of inter-linkages’. The use of the word ‘inter-linkage’ is deliberate, in two senses.

First, although I will talk a good deal about monetary policy and how it both impacts, and is impacted by, inequality, the interaction is wider than just monetary policy.

I am thinking of our actions in the areas of macroprudential policy, as a means for building resilience to shocks; in providing economic advice to the Government, to promote macroeconomic stability and long-term growth; and in implementing our consumer

protection framework which aims to ensure that the best interest of consumers of financial services are protected. These are all germane to inequality and today I will highlight some of our work in these areas in the context of the current levels

of inflation that we are experiencing.

Second, what do I mean when I talk about inter-linkages? This is simply the idea that the transmission of our policies, in terms of how they affect households, firms and the economy are affected by the level of inequality itself. This

applies to policies that aim to build resilience in the face of shocks, as well as to monetary policy changes that can impact employment, output and asset prices. Even though inequality remains outside central banks’ price stability mandate,

there is growing recognition that the distribution of income and wealth are relevant to the pass-through of monetary policy.1 And there is also evidence that monetary policy action, and non-conventional monetary policies in particular,

could be impacting on inequality

This gives you a flavour of the issues I will discuss today. But first I want to give some context, looking at recent trends in some key inequality metrics.

Inequality trends and resilience

Since the 1980s, both income and wealth inequality – and it is important to bear these distinctions in mind – have increased in many advanced economies. For incomes at least, Ireland is an exception as income inequality has not increased

but has actually fallen slightly since the 1980s, although the top 10% of earners still earned almost a quarter of total income in 2019.2 In the United States, just before the pandemic, more than 45% of pre-tax income, i.e. before redistributive

policies, went to the top 10% of earners, up from 34% in 1980.3

When we think of inequality within countries, the main factors driving increases in inequality in advanced economies include globalisation, technological progress and taxation.4 Globalisation and technological progress have adversely

affected the wages and employment of lower-skilled labour, while declines in the progressiveness of the tax system in some countries has contributed to increases in post-tax inequality. Overall therefore, the rise in income inequality has been driven

mainly by structural policies and long-term secular trends. Taking a more global perspective – that is, across countries – global income inequality has actually decreased since the 1980s. This is mainly as a result

of relatively stronger economic growth in developing countries, when compared with developed economies.

In most countries, the distribution of the household wealth tends to be much more concentrated than the distribution of income. For Ireland, we know this from data collected in the "Household Finance and Consumption Survey (HFCS)". This survey on

household assets, debt and wealth, has been a key part of our policy research and analysis since 2013, when the first survey was commissioned by Professor Patrick Honohan as Governor of the Central Bank. This survey, and subsequent waves in

2018 and 2020, all of which have been carried by the Central Statistics Office (CSO) in Ireland, shed further light on the evolution wealth inequality in Ireland.5

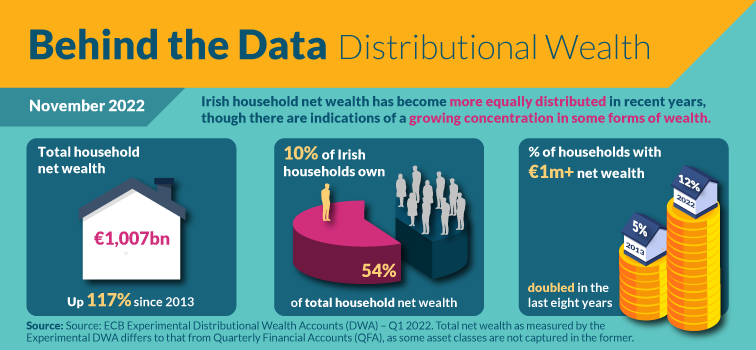

Building on this data, and working with other Eurosystem central banks, we recently published new Distributional Wealth Accounts which allow for analysis of the wealth distribution of households at a higher quarterly frequency. This data tells us that Irish household net wealth has increased significantly in recent years, with

net wealth inequality also declining (see the infographic in Chart 1). However, findings also point to a growing concentration of assets among wealthier households.

Chart 1. Headline results from distributional accounts

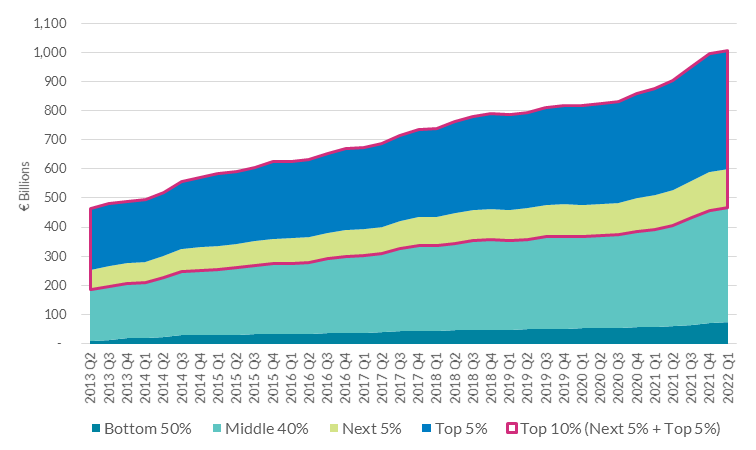

Between Q2 2013 and Q1 2022, the collective net wealth of Irish households’ grew by €544 billion (Chart 2). The Top 10% of wealthy households accounted for almost half of this growth, the bottom 50% accounted for 12%, with the

remainder of the increase related to the Middle 40% of households by wealth.

Chart 2. Changes in net wealth across the distribution

Source: Daly (2022)

Notes: Wealth groupings are based on the net wealth distribution: the top 5% of the distribution (95% to 100%), the next 5% of the distribution (90% - 95%), the following middle 40% (50% to 90%) and the bottom 50% of the distribution (0% to 50%).

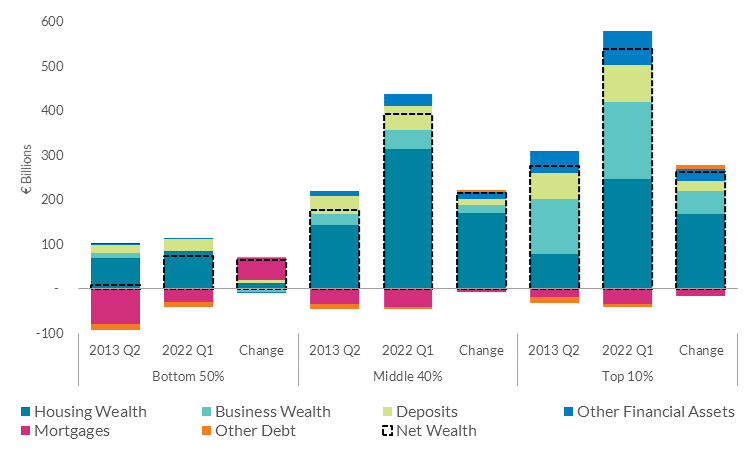

Approximately 80% of the increase in the net wealth for the Middle 40% over this period can be attributed to increases in housing wealth (Chart 3), with the remainder a combination of growth in business wealth, deposits and other financial assets.

Housing wealth also represents a significant share (64%) of the increase for the Top 10%, though growing business wealth and financial assets are also important.

With high levels of home-ownership in Ireland (70%), it is not surprising that changes in asset values (house prices) and housing related debt (mortgages) play an outsized role in driving wealth inequality trends in Ireland.6 Indeed, the

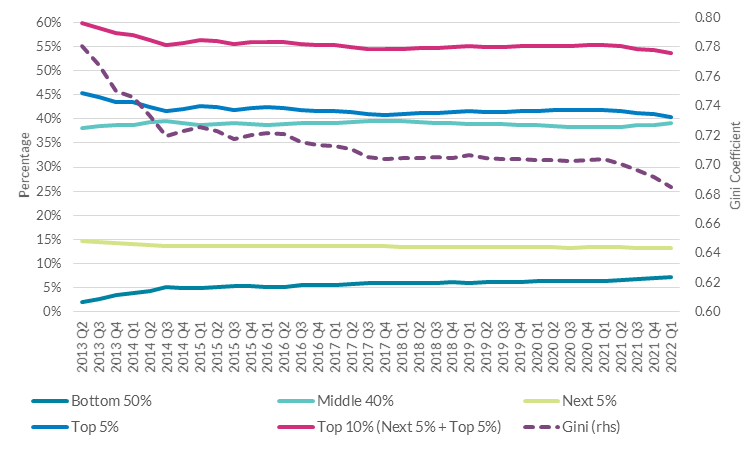

fall in headline wealth inequality metrics since 2013 (Chart 4) can be largely attributed to the gradual decline in the proportion of households in negative equity since then, both via deleveraging, but also rising house prices.7

Chart 3. Wealth Structure & Change Along the Net Wealth Distribution

Source: Daly (2022)

Notes: Other Financial Assets include debt securities, listed shares, investment fund shares, and life insurance and annuity entitlements, they do not include pension entitlements or currency given low comparability between the HFCS and QFA. Business wealth includes financial business wealth (unlisted shares and other equity) and non-financial business wealth (e.g. business property and land)

Chart 4. Wealth Structure & Change Along the Net Wealth Distribution

Source: Daly (2022).

Notes: A Gini coefficient of ‘0’ implies perfect equality (i.e. where all households have the same level of wealth), while a Gini coefficient of ‘1’ expresses maximum inequality (i.e. where one household holds all the wealth).

Differences in the home-ownership rate can lead to differences in wealth inequality across countries. For example, wealth inequality as measured by the Gini coefficient tends to be lower in Ireland, when compared with the likes of Germany and

Austria, where home ownership rates are lower.8

Increasing household indebtedness is also one of the key reasons for the long-run increase in wealth inequality in Ireland over the last three decades. As Lydon, Horan and McIndoe-Calder (2021) show, inequality rose between 1987 and 2018 due in large part to households in the middle of the wealth distribution acquiring more debt in order to purchase housing (i.e., increasing leverage).

There are echoes here of Thomas Piketty’s and others’ arguments around the rise in income inequality in developed countries, and the related erosion of purchasing power, which in turn contributed to increased household indebtedness

for consumption in the run-up to the financial crisis (although the increase in debt in this case is more about acquiring an asset than maintaining consumption). Nonetheless, it is a key distributional issue for the Central Bank when

we consider the resilience of households to shocks, and in the design of our macroprudential measures to promote financial stability. As history has taught us, it is only often when the tide goes out that we see the vulnerabilities

in relation to distributional imbalances that have been allowed to build up.

Our borrower-based macroprudential measures – which limit the amounts households can borrow in relation to both the value of the property and their income – are designed to strengthen the resilience of borrowers, lenders and the economy

overall. The recent review of the measures reaffirmed our commitment to the tools as a means of guarding against very high levels of indebtedness and unsustainable

lending in the housing market.

As we outlined in our first (PDF 1.74MB)Financial Stability Review of 2022 (PDF 1.74MB), household vulnerabilities are different to what we saw at the onset of the financial crisis in

Ireland. Resilience is underpinned by debt levels that have fallen steadily over the last decade, an increasing reliance on longer-term fixed rates that leaves fewer borrowers exposed to rate rises in the short-term9, as

well as some households holding considerable savings built-up during the pandemic. However, as we have highlighted in (PDF 563.14KB)our research (PDF 563.14KB), these savings are likely to be unevenly distributed,

with more than half of savings concentrated in the top 30 per cent of households by income.

But we do not take this resilience for granted, especially in the face of persistent shocks. Our ongoing analysis of household responses to high inflation and income variability ( Lydon (2022 (PDF 237.71KB)), Arrigoni et al. (2022) (PDF 3.04MB), Adhikari (2022) (PDF 349.52KB)) as well as to interest rate rises ( Lyons et al (2022, FSR 1, Box C (PDF 1.74MB))) will continue to highlight groups

that are most vulnerable, allowing for appropriately target measures to be implemented.

Next, I want to move onto price stability and monetary policy, and how this interacts with inequality.

Price stability, monetary policy and inequality

Though central banks actions can have an impact on the distribution of wealth and income over shorter horizons, over the longer run their impact is likely to be small. As a tool that is primarily aimed at tackling cyclical fluctuations,

monetary policy is unlikely to be a substantial driver of structural inequality. We know that downturns can lay bare the different types of inequality that are lurking beneath – as I mentioned above – but, the sources

of inequality run deeper and, I believe, are more structural in nature than they are cyclical.

But this does not mean that, as monetary policy makers, we should ignore it. This was one of the key messages we heard from the general public and representative groups when we conducted our own ‘listening exercises’ as part of the ECB’s 2021 strategy review. To the extent that monetary policy has

significant redistributive effects, it will of course impact inequality, at least in the short term. But an equally – if not more – important issue is how inequality can also impact monetary policy. In other words, how pre-existing

levels of inequality – either in income and/or wealth – impact how monetary policy is transmitted to households, firms and overall economic activity.

There has been an explosion of research on this issue in recent years.10 Much of it focuses on how monetary policy changes – for example, increasing or decreasing interest rates, or purchasing assets – affects different

types of households according to income, job-type or wealth. When I talk about ‘conventional’ monetary policy, if there are more households in society whose consumption is very sensitive to income changes – typically

those with limited access to credit, or fewer savings – then the transmission of monetary policy to the real economy tends to be stronger. Our recent Central Bank Quarterly Bulletin article on “Household Economic Resilience” (PDF 3.04MB), emphasised this issue

by quantifying for the first time the joint distribution of income and wealth across Irish households. We estimate that between 6 and 15 per cent of Irish households could be considered to be in a precarious position in relation to

income risk, while also holding little – if any – in the way of savings buffers.

All of this goes to show that portfolio compositions of different households (for example, liquidity and debt) matter for the transmission of policy, as well as when they interact with the precariousness of income. But, for macroeconomic

and monetary policy, distributional issues are not just confined to income or wealth. As I have highlighted previously on the macroeconomic challenges from an ageing society, the distribution of age-cohorts across the population

also matters. I think of this as the demographic channel for the effectiveness of monetary policy. As we all know, populations around the world – and especially in developed economies in Europe and the US – are ageing.

If populations save more as they age, which is generally what we see in the data, then a greater stock of savings in the future as a result of older populations could blunt the effectiveness of monetary policy.11

The primary goal of monetary policy is to maintain price stability. This means preserving the purchasing power of the euro by ensuring low, stable and predictable prices. The Governing Council of the ECB – consisting of the 19 (soon

to be 20) national central bank governors and six members of the ECB executive board – has decided that the target of price stability is an annual rate of inflation of 2 per cent. We are clearly very far from this right now. Although

nominal interest rates have been rising, monetary policy still has a way to go to restore price stability, a pre-requisite for sustainable growth. Interest rates have been increasing for the first time in a decade (by 50bps in July,

75bps in September and 75bps in October), and they are now well out of negative territory. The future direction of travel is also clear: we expect to raise policy rates further in order to sustainably achieve our 2 per cent target over the

medium term. I realise that economic indicators point to a deterioration in the outlook for economic activity in the euro area, with growth projections from the ECB and other institutions being revised downward for 2023 and 2024. However,

this slowdown in growth will not on its own be enough to ensure inflation returns to its target of 2% in the medium term.

While maintaining price stability is our primary objective, we are also conscious of other interactions and side-effects of our policy actions, and take them into account when formulating policy. Indeed, as we reiterated following the 2021

strategy review, we base our monetary policy decisions, which include an evaluation of the proportionality of those decisions and their potential side effects, on an integrated assessment of all relevant factors. We will continue to

do that.

While monetary policy has important consequences for the entire economy, not every household will be affected in the same way. The effects can also vary according to which particular policy is being implemented. And here I want to

make the distinction between changes in interest rates – sometimes labelled ‘conventional’ monetary policy – and changes in the central bank balance sheet – sometimes labelled ‘unconventional’ monetary

policy.

Conventional monetary policy – or changes in main policy rates

The direct effects of rate changes on income are relatively straightforward to understand. In the case of an increase in interest rates, the interest paid, for instance on deposits, will rise, increasing the financial income earned by households

with savings, who are typically wealthier households, but also many retirees. On the other hand, those who have loans, especially on variable rates (and those on fixed rates once the fixation period expires), will see the repayments on their

loans increase, and as a consequence their disposable income after debt repayments will fall. This effectively results in a transfer of income from borrowers to savers, which has implications for inequality.

Looking at the impact on wealth, when the central bank increases interest rates, asset prices typically decline reflecting the expected adverse effect of tighter monetary policy on the economy. With the rising cost of money, bond prices decline

and their yields increase; while house price growth slows as higher mortgage rates and a weaker economy discourage more borrowing and house purchases. Typically only those at the very top of the wealth distribution are affected by changes

in stock prices, although these have an impact on retirement savings as well. Meanwhile, the impact of movements in house prices often have an ambiguous effect on inequality, as it is households in the middle of the income and wealth distribution

that generally own their own home.

More generally, the direct effects of changes in interest rates depend on the types of assets a household owns and if they have borrowed to accumulate them. Furthermore, the magnitude of these effects will depend on the relative and absolute size

of each of these assets in the household’s portfolio. On balance the literature12 tells us that, when looking at the impact through this narrow lens, falling rates are beneficial in reducing inequality, particularly income

inequality in the short-run, while raising rates can work against it.

Unconventional monetary policy – changes in the size of central bank balance sheets

Quantitative easing, which is the purchase by the central bank of sovereign and other bonds on the secondary markets, works for the most part through its effects on asset prices (including housing) and longer-term interest rates, by increasing

the former and lowering the latter. As we know, increases in equity and bond prices tend to typically benefit wealthier households who are more likely to hold such assets. However, evidence also shows that the opposite end of income and wealth

distribution also benefitted from asset purchases as a consequence of increasing employment that benefits lower-income households in particular.13 Higher levels of borrowing by households and firms, led to higher consumer spending

and investment, with a positive effect on GDP and employment. This is thought to have decreased income inequality as employment rises with aggregate demand, and lower income households benefit disproportionately from cyclical employment expansions.

For wealth inequality the literature is less conclusive.14 It is difficult to quantify the effects, but they might be U-shaped, with the policy benefiting households at the very top (due to rising asset prices) as well as

the very bottom (due to increasing employment) of the wealth distribution.

However, we now find ourselves in a very different environment, and the ECB like many other central banks is considering ways to reduce the size of its balance sheet. It might be tempting to assume that the effects of reducing the size of the

balance sheet will mirror the effects from increasing it, but there are some key differences. The primary difference now is the context. The current high inflation is having a very negative impact. Falling real incomes mean lower consumer

spending as households reduce spending on non-essentials, and divert more of their budget to items such as food and energy. For households that spend relatively more of their budget on items that are rising fastest – such as energy

and food – the effect can be particularly acute, as we have shown in recent Central Bank research (PDF 237.71KB). As a result, inflation is often justifiably portrayed as a regressive tax. Indeed,

within an environment of stable prices, it is easier for firms and households to plan for the future, and for Governments to invest in policies (such as health and education) that promote wellbeing, and support the purchasing power of households,

especially those on lower incomes. By laying the foundations for a more stable macroeconomic environment, monetary policy can thus help those policymakers that do have the power to create the conditions that improve the conditions for the

most vulnerable. As I said in my letter to the Minister for Finance (PDF 4.71MB) in advance of Budget 2023, there is a role for fiscal policy in supporting

those most vulnerable to the current high rate of inflation. However, supports should be temporary, tailored and targeted, to make the most of limited resources as well as limiting the risks of adding further to inflationary pressures.

The current macroeconomic environment is unprecedented as we tighten monetary policy while facing a higher probability of a global recession. There are costs to firms and households in terms of raising rates with adverse implications for inequality.

However, these factors have to be off-set against the costs of high inflation which if left untreated in a timely and effective manner, will have far greater macroeconomic consequences. That is why we at the ECB cannot allow ourselves

to deviate from our primary objective, which is price stability.

Credibility and communication

Credibility is a key element of effective monetary policy. Credibility and good communication go hand-in-hand. As I have outlined before, I believe transparency, honesty and engagement help to build credibility and to set expectations.

Trusting the Central Bank’s commitment to price stability, and understanding exactly how it plans to go about achieving it, influences the public’s (and financial markets’) inflation expectations.

A lack of trust weakens the central bank and makes it vulnerable to political pressure. So central banks, like all institutions, need to build social capital. There are many definitions but I like to think of social capital as “the social

connections, attitudes and norms that contribute to societal wellbeing by promoting coordination and collaboration between people and groups in society”15. Trust is stronger where social capital is strong. Central banks can

help build social capital through their actions but also through their communications. In uncertain times, such as we are living in today, this matters. The ECB will deliver on its mandate of price stability. Our credibility is demonstrated by our monetary policy actions

that are consistent with reaching our inflation target, and by communication that reiterates our objective and how we intend to achieve it.

Conclusion

The distribution of income and wealth is something that central banks need to pay close attention to, not least because it has policy consequences as well as implications for social capital and the public’s trust. Central banks

need trust to succeed. And trust is stronger where social capital is strong. Social capital is an important determinant of a community’s wellbeing, alongside human capital, natural capital and financial and physical

capital, what I like to describe as our collective economic capital.16

Although central banks do not have the mandate or the tools to deal with societal concerns around income or wealth inequality, they can help build social capital through their actions and by continuing to focus on fundamentals.17

Successful economies need stable and sustainable macroeconomic frameworks and sound monetary policy that delivers predictable prices. They also need stable and well-regulated financial systems and well-functioning markets. At the Central

Bank, we will continue to focus on our core mandate of price stability, a stable financial system and the protection of consumers. In the current inflation environment, the priority for monetary policy has to be achieving our target

of 2% inflation over the medium term.

Price stability is a pre-condition for economic growth and the best contribution central banks can make to ensuring society has the resources to address the structural factors that drive inequality in society.

Price stability means we are providing the macroeconomic basis for sustainable and long-term investment in education, health, housing, and, ultimately, being able to provide access to essential public services at reasonable cost and supporting

the welfare of the people as a whole.18

5 The HFCS is a multi-country survey of household wealth carried out across the Eurozone. Since the first wave in 2013, the CSO has made several key methodological advances in the survey since it inception, putting it at the

frontier of data collection in this field. This includes the use of multiple administrative datasets for the collection of information on incomes, asset values and, crucially, debt. For more background on the Household Finance

and Consumption Survey (or ‘HFCS’), see, amongst others, Arrigoni, Boyd and McIndoe-Calder (2022) (PDF 3.04MB), ECB (2018) and CSO (2022).

6 Ireland’s home ownership rate is around the EU average of 69.9%. However, there are some significant differences across the EU, for example: Germany 49.5%, France 64.7%, Italy 73.7% and

Spain 75.8%.

9 In just the last decade, there has been a significant shift towards fixed-rate mortgage loans in Ireland. In 2010, for example, just 13% of outstanding loans were on a fixed rate; by 2022 this had risen to around 55% of outstanding

mortgages, with 88% of new loans opting for a fixed rate period.

11 In a recent paper presented at a Central Bank of Ireland seminar, Professor Joseph Kopecky from Trinity College, Dublin highlighted very similar issues, albeit in the context

of ageing populations in the likes of the US, Japan and other European countries.