The Central Bank’s balance sheet

31 October 2023

Blog

I have just returned from a busy week, where I visited my Governing Council colleague Governor Constantinos Herodotou in the Central Bank of Cyprus (and met senior officials and local business people) and also attended the ECB’s Monetary Policy meeting in Athens. At the latter, we decided to keep the three key ECB interest rates unchanged. The incoming information broadly confirmed our previous assessment of the medium-term inflation outlook with inflation still expected to stay too high for too long, and domestic price pressures remaining strong. Our past rate increases continue to be transmitted forcefully into financing conditions and are increasingly dampening demand, thereby helping to push down inflation. Our assessment remains that the key ECB interest rates are at levels that, maintained for a sufficiently long duration, will make a substantial contribution to the timely return of inflation to our 2 per cent medium term target.

Interest rates are our main policy tool to return inflation back to our target but they are not our only tool. I’ve been reflecting on the role of central bank balance sheets as a policy tool, and I want to share some of those thoughts in today’s blog.

Euro area

The interest rate decisions that we have taken over the last year have been in response to inflation being above our target but in the years leading up to the pandemic, the euro area faced inflation below that target. Monetary policy was both highly accommodative and unconventional as we aimed to increase inflation to the target. We used our main policy tool – interest rates – and set them at low and even negative levels. But we also used another policy tool – our own balance sheets – to undertake asset purchases (largely but not exclusively sovereign bonds) aimed at putting more liquidity into the financial system to support the transmission of monetary policy to the economy.

As we know, the era of very low inflation was brought to an end by a combination of shocks, not least Russia’s war on Ukraine and its people, the disruption of supply chains in the wake of the pandemic and the recovery of activity as economies re-opened. In response we have raised the three key ECB interest rates by 450 basis points since July 2022. The Eurosystem - and indeed Central Bank of Ireland - holdings of monetary policy securities are gradually reducing as we slow down our asset purchases. But of course, once purchased, bonds don’t disappear from the balance sheet. Most of our holdings following the Governing Council’s decisions include longer-dated sovereign bond holdings purchased at low or even negative yields. These low-yielding securities (in the Central Bank’s case, they have an average weighted yield of 0.61 per cent) contrast with the fact that we pay interest at the ECB’s policy rates (of at least 4 per cent) on any deposits that banks hold with us. In other words, we have an interest rate mismatch where the interest we pay on monetary policy liabilities is increasing more rapidly relative to the interest that we receive on our bond holdings.

This combination of the cost of liabilities exceeding income has led to certain euro area central banks releasing provisions to cover losses already in their 2022 annual accounts. A rising interest rate environment can also result in valuations losses on bond holdings held within foreign reserves and non-monetary policy portfolios, thereby lowering or completely eliminating any income contribution from other central bank assets. For example, the ECB reported a zero profit in 2022 after the release of €1.6 billion from provisions for financial risk1. The provision was used to cover losses that arose from the higher interest expense on liabilities and unrealised price losses on securities. Similarly, other national central banks from across the euro area (namely Austria, Finland, Germany and the Netherlands) have thus far reported releasing provisions to cover risks like these materialising in 2022 and some have warned of expectations of losses in the years ahead.2

Central Bank of Ireland

We are on a similar journey. To repeat, the central bank’s balance sheet is a policy tool. Our task is not to make profits but to ensure price stability. We have always known that, at some point, monetary policy actions to achieve price stability could result in losses on our balance sheet. We identified these risks a number of years ago and have been taking prudent actions to prepare for such an eventuality.3

One particular feature of the Central Bank’s profits in recent years has have been the impact of the realised gains on sales of the Special Portfolio (assets that were acquired in 2013, as part of the liquidation of the Irish Bank Resolution Corporation but on the expectation that they would be disposed of as soon as financial conditions allowed4).

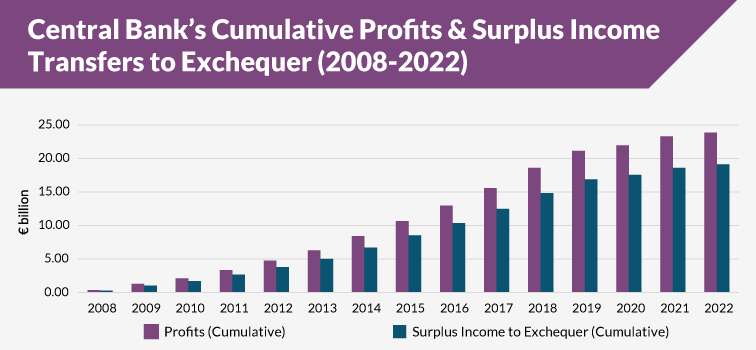

Chart 1: Central Bank’s Cumulative Profits and Surplus Income Transfers to Exchequer (2008-2022)

The Portfolio has been an important contributor to the Central Bank’s profitability with cumulative realised gains since 2014 of €12.5 billion (at end-2022) representing 89 per cent of the income we paid to the Exchequer over the same period. As of last month, all of the Special Portfolio has been sold and, as a result, it will no longer be a source of income for us while, at the same time, we are exposed to the interest rate mismatch I explained earlier. Moreover, the return on the Bank’s investment assets is also expected to take time to adjust to the rising interest rate environment, given the impact on returns of accommodative monetary policy in previous years and possible valuation losses on bond holdings as rates increase.

Building resilience

In order to mitigate the increased financial risks facing the balance sheet, we have been strengthening our overall financial buffers. Each year since 2008, we have set aside the maximum 20 per cent of profits allowable (under legislation) to increase our General Reserve from €1.2bn in 2008 to €5.9 billion in 2022. We also introduced a General Risk Provision policy in 2016 to allow us to make provisions for the additional financial risks (in particular interest rate mismatch risk).5

The Central Bank reported an overall profit of €0.575 billion in 2022.6An additional €1.2 billion was added to the General Risk Provision (bringing the total to €3.0 billion), while the maximum 20 per cent of profit has been retained in the General Reserve. Our aim is to strengthen financial risk and resilience management given our expectation of losses in the coming years.

Conclusion

I expect us to report losses in the years ahead as a result of the monetary policy measures taken in the pursuit of price stability over the past decade, coupled with the current level of interest rates to return inflation to our target. But that is one of the consequences of having our balance sheet as a policy tool and our overriding commitment to deliver price stability.

Gabriel Makhlouf

4 As part of the liquidation of the IBRC in 2013, the Central Bank acquired additional assets to the value of approximately €42.6 billion primarily in the form of long-dated €25 billion Irish Government Floating Rate Notes (FRNs), €13.7 billion NAMA bonds, and €3.5 billion of the Irish Government 2025 Fixed Rate Bond.

Read more: