Public policies to support firms through COVID-19

08 July 2020

Blog

This week I’ve participated in online discussions with IBEC and with the Chambers of Commerce in Galway and Cork (and later today with those in Dublin and Limerick) and appeared before a Special Committee of the Oireachtas. These engagements have allowed me to listen to views from around the country and to outline my thoughts on the policy responses of both fiscal and monetary authorities, as well as offer some considerations for future policy, following on from the analysis we published last week in our third Quarterly Bulletin of the year.

One of the main points regarding the future – and I also put it in a letter to the Minister for Finance (PDF 341.84KB) last week – is that policy should continue to focus on supporting the productive capacity of the economy and avoiding scarring effects such as long-term unemployment. A key element of policy comes from Government support measures to reduce the risk of failure for otherwise viable firms. Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs, i.e., firms with less than 250 employees) are particularly relevant here. Data from last year indicates that SMEs accounted for over 1 million employees, or 68.4% of total employment in the Irish business economy. And previous research (PDF 509.29KB) has shown that younger firms are particularly important for job creation.

The outlook for firms

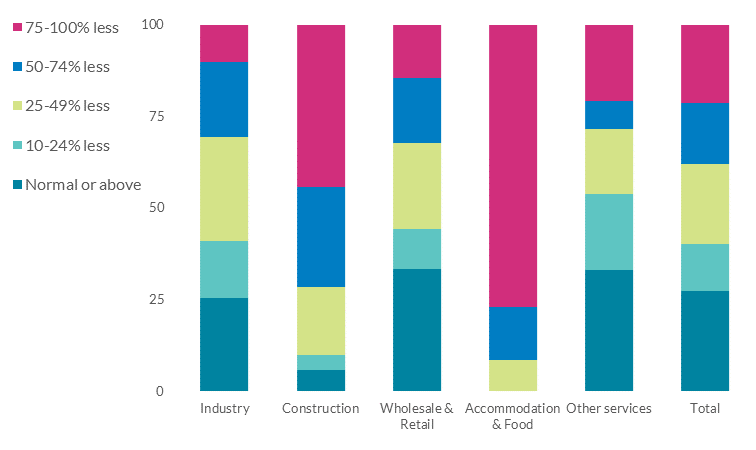

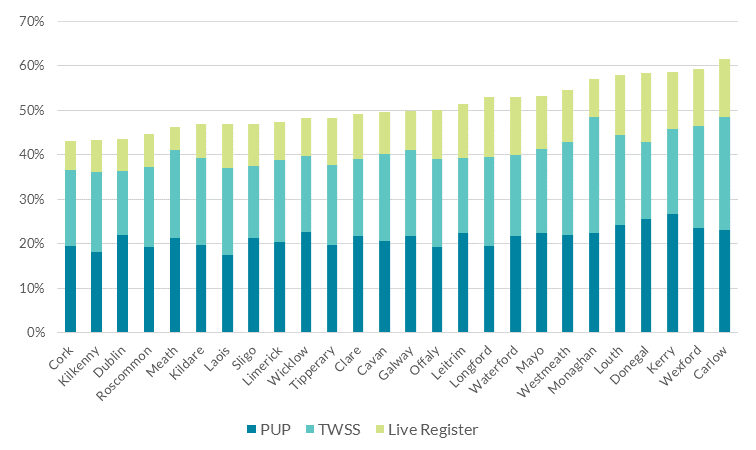

The current crisis will have longer-lasting effects if otherwise viable firms go out of business. But distinguishing between long-term viable and unviable enterprises is difficult in these uncertain times. Traditional economic signals – such as sales or profits – are not representative of “normal times”. Firms have played their part in the overall public health response by closing their doors with the decline in revenue being much greater for certain sectors in the economy, particularly for accommodation and food (see Figure 1). The effect of the crisis has also differed across the country (see Figure 2).

Figure 1: Declines in revenue differ by incidence and intensity across sectors

Source: CSO

Notes: Share of firms by revenue relative to normal conditions (CSO, 4th May to 31st May)

Figure 2: Share of labour force in each county on PUP or TWSS, or on the Live Register

Source: Regional Labour Market Impact of Covid-19, Box E, Quarterly Bulletin 3 - July 2020.

Some enterprises undoubtedly had unsustainable business models before the onset of COVID-19, and during a typical downturn their closure would be seen as part of the overall process of economic restructuring. However, in current circumstances, erring on the side of giving enterprises a degree of protection and flexibility is, in my view, preferable and should lead to better long-term outcomes, notwithstanding that a certain amount of churn is part of the normal functioning of an economy. Measures that provide time for firms to adjust to the “new normal” – or to assess whether their business models remain viable – are particularly useful during a period of substantial uncertainty. They also allow lenders to make more informed decisions on a firm’s viability.

It’s also important to bear in mind that an enterprise is more than a revenue stream for its owner. It is often an eco-system within a local economy (PDF 910.92KB), with relationship-specific capital tied up in its links to employees, suppliers and customers. This capital is not readily re-created in the aftermath of widespread insolvency events.

Policy options

The Government has already acted to provide liquidity support to firms, most notably through the Temporary Wage Subsidy Scheme to support payroll expenses. However, even with this support in place, the nature of the COVID-19 shock means that there is a cohort of firms that are likely to need additional support to survive through this period of heightened uncertainty. There are a suite of policy options (PDF 486.78KB) available to provide support to overcome short-term liquidity problems, including loan guarantees, direct lending and expense deferrals, and grants and expense waivers.

Debt based solutions have the advantage of speed and access to information. And as I’ve outlined previously, the majority of SMEs entered this period with no outstanding bank debt, due to substantial deleveraging in recent years; 57 per cent of SMEs report that they have no bank debt and just 6 per cent have debt to turnover ratios of greater than 50 per cent (see Figure 3). So, from a macro perspective, SMEs may have some capacity to take on debt to meet current outgoings.

Figure 3: Share of SMEs in debt-to-turnover (DT) ratio bands by exposure to COVID-19

-ratio-bands-by-exposure-to-covid-19.png?sfvrsn=dfd9851d_4)

Source: Department of Finance Credit Demand Survey

Notes: Data are as of September 2019, categories defined according to sector exposures to COVID-19.

Indeed, banks have far more information than governments on their SME clients that they can use to determine if a business is likely to be viable. They can leverage their relationships to allocate credit to those businesses that are the most robust, something that should be considered when designing a credit guarantee scheme for example. There is a trade-off between providing credit as quickly as possible and ensuring that lenders are incentivised to use their knowledge and expertise to make sure that credit is being provided where it should be. A 100% loan guarantee is likely to reduce the incentive for lenders to screen applicants thoroughly and could result in greater risk for the guarantor (who, in the case of a state-backed guarantee, will be the taxpayer). This of course needs to be set against the potentially larger volume of liquidity provided by such schemes and the greater speed at which it could reach firms. My view is that, while speed is of great importance in the current crisis, well-designed incentives for lenders have a role to play in ensuring that guarantees are effective and offer value to the taxpayer.

I recognise that an over-reliance on liquidity support through debt may not be the answer for every firm. The experience of the last crisis means that viable but risk-averse SME owners are reluctant to take on debt. Given this, a wide policy mix may be necessary to achieve the goal of minimising scarring from the current crisis. However, if any additional non-debt support is to be provided – such as equity participation for example – it should be targeted to where support is needed the most.

The role of lenders

As credit institutions will also administer the guaranteed lending, the resilience of the sector becomes ever more important.

The banking system has already provided considerable support to households and businesses through payment breaks which are also likely to have important macroeconomic benefits. They can be seen as part of the risk-sharing function that the financial sector would ideally provide to the real economy during times of unanticipated stress.

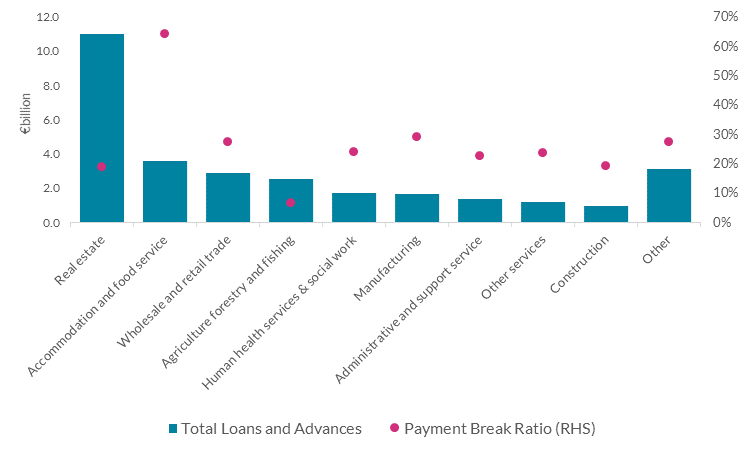

Tomorrow we will publish some analysis which will show that there are payment breaks across all 19 categories of economic activities of SMEs, with most of the impact in the top 5 sectors in terms of SME loans (i.e., real estate, accommodation & food services, wholesale & retail trade, agriculture, forestry & fishing, and human health services). Figure 4 shows that accommodation and food is an outlier, with almost two thirds of loans linked to a payment break.

Figure 4: SME Payment Breaks (Total SME Lending and % of Lending with a payment break)

Source: Central Bank of Ireland, forthcoming.

Notes: Other is an aggregation of individual sectors where loan balances were below €900 million. Payment break ratio is the total value of payment breaks / total loans and advances.

The payment breaks are temporary and debt restructuring will inevitably be required in the case of some corporate and SME borrowers. We expect lenders to engage constructively to arrive at solutions that are sustainable over the long-term for the borrower. And given the amount of uncertainty surrounding the outlook, some additional time-bound forbearance may be appropriate as the payment breaks expire.

Conclusion

Firms are a crucial component of the recovery. But they will also need to be ready to adapt to challenges beyond the current crisis, whether as a result of the UK’s withdrawal from the EU, or the ongoing march of digitalisation and its impact on skills and business models, or the impact of climate change. These are topics for future blogs!

Gabriel Makhlouf

Read More