Remarks by Governor Gabriel Makhlouf at The Economist 18th Annual Cyprus Summit

18 October 2022

Speech

Good morning from the other end of the European Union. Let me say a few words on monetary policy and NPLs.

Monetary policy

First, monetary policy.

In the lifetime of the euro, inflation has reached record highs. Headline inflation was 10% in the euro area and 8.6% in Ireland in September. This marks a rapid shift from the low inflation we experienced for much of the decade before the pandemic: in Ireland, inflation averaged just 0.5% per year in the ten years to 2019.

The initial impulse for higher inflation was the pandemic, in particular the lifting of restrictions, and the global supply bottlenecks that resulted from it. Russia’s war in Ukraine was a further shock impacting commodity prices, and especially gas prices. In August, food and energy price increases accounted for two-thirds of headline inflation in the euro area.

The persistent and overlapping nature of these shocks has had significant indirect effects.

The prices of many services and goods that rely on energy as an input have also risen sharply. We see this in the core inflation measure – stripping out energy and food price changes – which has risen steadily over the year to stand at 4.8% in September.

The number of items in the euro area HICP basket with price increases of greater than 2% has been rising. Now, more than six out ten items in the basket are seeing price increases greater than 5% year-on-year.

As price pressures broaden across the basket, the case for tighter monetary policy becomes stronger.

It is sometimes said that, as it operates primarily through aggregate demand, that monetary policy should ‘look through’ supply shocks. To an extent, this is correct, and it is a view that underpins the medium-term orientation of our monetary policy strategy. This is not, however, an argument to do nothing in the current climate. We need to pay close attention to supply-demand imbalances, and decide how significant these are, and what monetary policy needs to do to bring things back into balance.

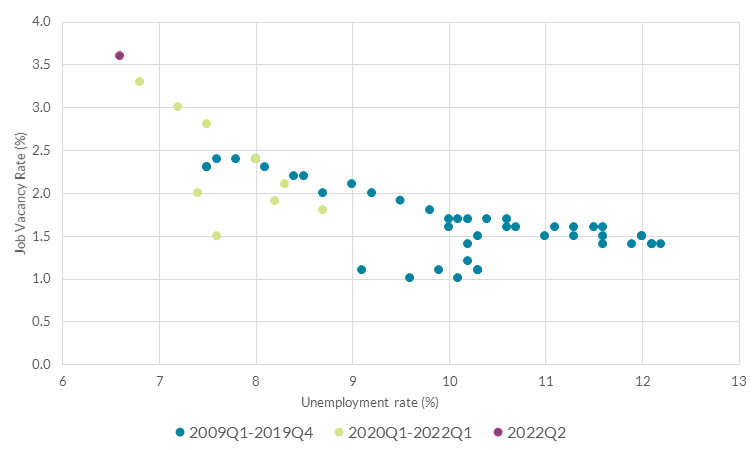

While the initial impulse for inflation was a sequence of supply shocks, it is quite clear that demand coming out of the pandemic has also been exceptionally strong. In the labour market, for example, labour supply shortages are still being reported by firms, even in the face of a deteriorating outlook. The Beveridge curve shows a historically tight labour market (Chart 1.1), with high job vacancy and low unemployment rates.

Chart 1.1 | Beveridge curve

Source: Eurostat for underlying data

We pay close attention to labour market developments, both as indicator of the economic outlook, but also for wage developments that could indicate persistently high inflation becoming embedded.

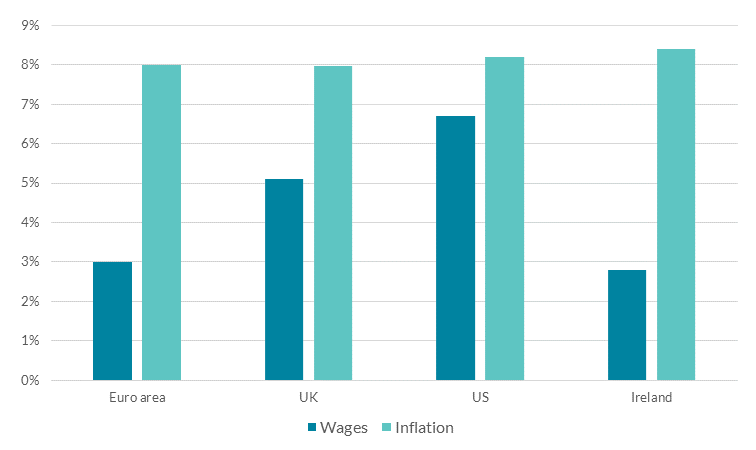

Wage growth estimates data show an acceleration of wage growth during 2022 (to 3% in Q2), but still lagging inflation (Chart 1.2). At the Central Bank of Ireland, we also track trends in posted wages, drawing on data from millions of job ads across the euro area. This data also points to an acceleration of wage growth, especially during the first half of 2022 as economies reopened after the pandemic.

Some degree of so-called ‘second round’ effects is to be expected as real wages catch-up. In fact, the current trends in both the official wage growth data and our posted wages tracker are broadly in-line with the ECB’s current projections for wages in 2023 to grow at around double the rate we saw before the pandemic. What we wish to avoid are third or fourth round effects, whereby expectations of higher inflation above target become embedded in wage demands, contributing to self-fulfilling inflationary dynamics.

Chart 10 | Wage growth & inflation, 2022

Source: National statistics bodies. EA, UK and Ireland is Q2 data, wages adjusted for job retention schemes; US wage/inflation data is September/August 2022.

Faced with the risk of persistently high inflation, the Governing Council increased rates by 50 and 75 basis points in July and September of this year. As we have signalled in our communications, further increases are expected.

The scale and pace of future interest rate changes needed to achieve our 2% inflation target will be based on the incoming data and the evolving outlook, what we describe as a ‘meeting-by-meeting’ approach.

A pivot to tighten monetary policy has been necessary. History teaches us that these issues will only be exacerbated if we delay action. Raising interest rates is absolutely necessary as persistent inflation is damaging to macroeconomic stability and longer term living standards.

NPLs

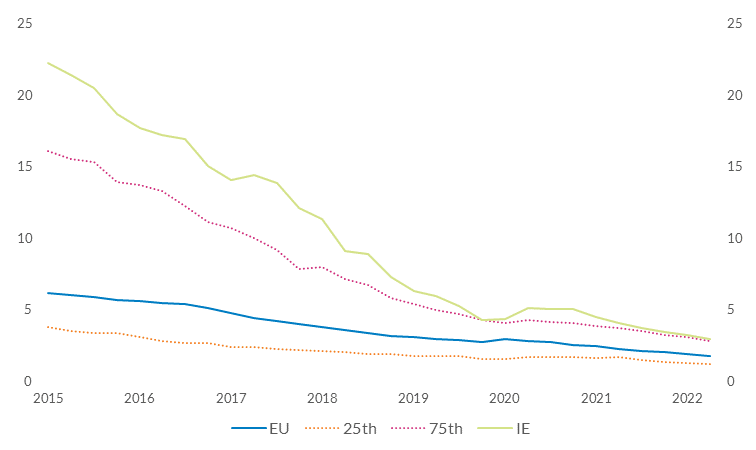

Turning to non-performing loans (NPLs), which, to some extent, were “the dog that never barked” during the pandemic. Thanks to the widespread deployment of payment moratoria, loan guarantees, and direct fiscal transfers and wage subsidies, the increase in NPL ratios experienced in Europe during 2020 was almost non-existent, and in most cases has been followed by subsequent declines into mid-2020 (Chart 2.1).

Given the labour market shock and GDP falls experienced, this is quite striking and shows the full force of the policy support deployed from March 2020.

Chart 2.1. NPL ratios across Europe

Source: EBA risk dashboard

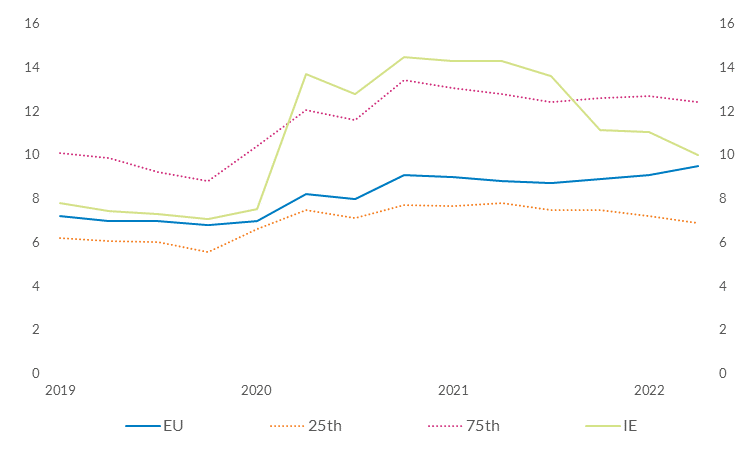

We must however remain vigilant. Roughly one in ten loans across Europe are classified as Stage 2, at high risk but not yet default (Chart 2.2).

Chart 2.2. Stage 2 loans across Europe

Source: EBA risk dashboard

These loans take higher provisions to account for their higher risk, and the prudent recognition by banks of these higher risks should ultimately make them more resilient to future adverse events. Households and businesses are now transitioning almost without a break from the pandemic-related shock to an energy-driven inflationary shock.

Resilience has been eroded, undoubtedly, and it is difficult to measure precisely how much latent distress is lurking under the surface, ready to be exposed by the interlocking nature of these shocks.

Fiscal support will again provide some absorption of this shock for many with bank debts, but there may be a limit to the role fiscal support can play in cushioning exposed businesses in particular from the profitability effects of this episode.

We in Ireland are acutely aware of how difficult it can be to repair bank balance sheets after a surge in NPLs. The post-2008 experience taught us that early engagement between borrower and lender is absolutely essential, as are strong frameworks for protection of consumers during that engagement, and a streamlined data collection and assessment process for distressed borrowers.

In recent years, banks benefited from global financial conditions by selling and securitising portfolios of NPLs to specialist market entities, as well as from economic recovery to support successful loan restructures. However, in a higher rate environment, we must not be complacent: it is not obvious that such a ready portfolio sales market, at an appropriate price, will remain available to banks, nor that loan restructures will prove as successful.

There are reasons to believe loan impairment dynamics, and the risk of potential balance sheet amplification by banks, are not as severe as during the post-2008 crisis. Nominal inflation in incomes and house prices may improve defaults and losses relative to previous shocks.

Finally, the level of capital headroom remains strong, and, as such, a negative credit supply response which could amplify economic stress is less likely than before.

On all of these fronts, we will remain vigilant, and ready to use releasable macroprudential tools if we deem it appropriate the counter-cyclical policy requires an easing of capital requirements in order to support the economy, in line with our financial stability mandate.

Conclusion

The euro area economy is facing a difficult combination of high inflation and low economic growth, including the possibility of a technical recession. It is an uncertain and challenging environment which is perhaps inevitable when a war is taking place on the continent and when the supply of energy has become an instrument of that war. The role of central banks has to be to focus resolutely on their core price stability mandate and governments need to think carefully about their fiscal policy choices and avoid those that would further fuel inflation.