Navigating Economic Cross Currents - Remarks by Vasileios Madouros at UCC as part of an outreach visit to Cork

23 May 2025

Speech

[1] Just miles from here, off the southwest coast of Cork, the Atlantic does not flow uniformly. Tides push in one direction and swells in another. Cross currents are a fact of life at sea, and even experienced sailors need to stay alert. The aim is not to avoid cross currents, but to recognise them, be ready to respond, and keep steering with purpose.

Cross currents are also a fact of economic life. And we are navigating one at the moment. In one direction, global shocks are weighing on the domestic economic outlook. In the other, the domestic economy is entering this period from a position of strength, and – if anything – has been bumping up against domestic capacity constraints.

Today, I would like to expand on how these different forces are shaping the economic outlook and discuss the implications of these developments for domestic economic policy.

The outlook for global growth has shifted downwards

Let me start with the global context. Since the beginning of the year, we have seen three interrelated shocks affecting the international economy. A material shift in trade policy; a sharp increase in policy uncertainty; and an increase in market volatility. Without a change in direction, these will continue to weigh on the global growth outlook. Let me briefly cover each in turn.

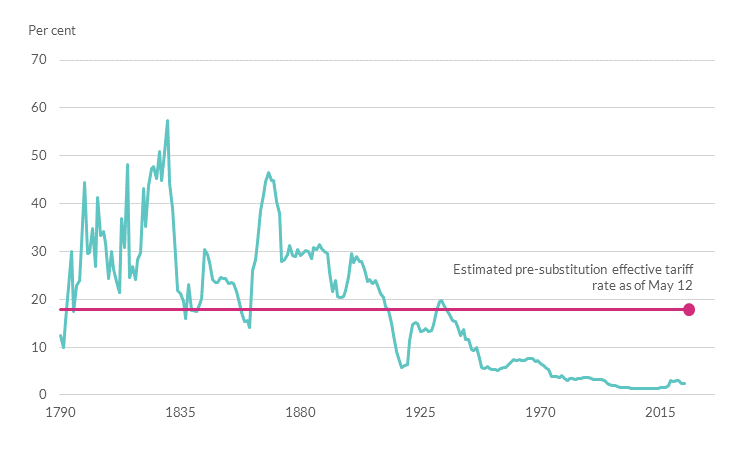

On trade, the policy shifts by the US administration – and the countermeasures by its trading partners – have led to a material increase in effective tariff rates. This is most notably the case in the US, where the effective tariff rate on imports has increased by several multiples since the beginning of the year. Even following the recent agreements with China and the UK, the effective tariff rate on US imports remains at its highest level since the 1930s (Chart 1). This, in and of itself, will harm trade and growth. It represents, in effect, an acceleration of recent trends towards greater fragmentation of the global economy, driven by geopolitical factors.

Chart 1: Effective tariffs rates on imports into the US have increased to multi-decade highs  This trade policy adjustment has not been smooth. Indeed, in recent months, it has been accompanied by a sharp increase in policy uncertainty. There are different measures of perceived uncertainty, and the one that tracks uncertainty in relation to trade policy has reached levels that are without recent historical precedent (Chart 2). Uncertainty – in and of itself – also harms trade and growth. If companies do not know what tariffs they might face, they will be reluctant to expand production or to invest. Indeed, economically, uncertainty acts much like a tax, but without any associated revenues.

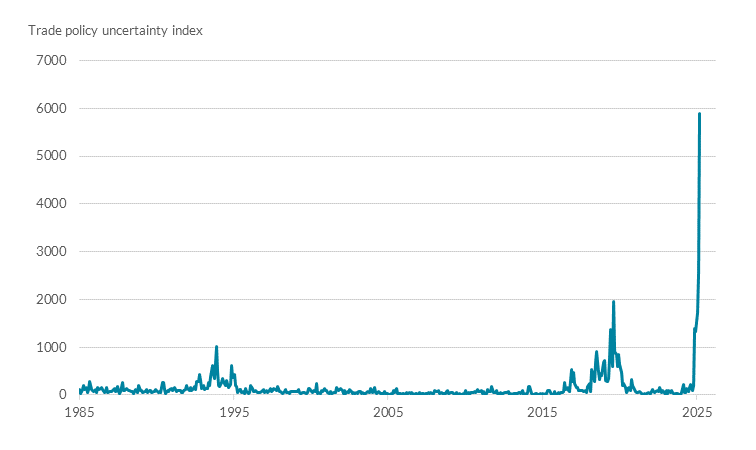

This trade policy adjustment has not been smooth. Indeed, in recent months, it has been accompanied by a sharp increase in policy uncertainty. There are different measures of perceived uncertainty, and the one that tracks uncertainty in relation to trade policy has reached levels that are without recent historical precedent (Chart 2). Uncertainty – in and of itself – also harms trade and growth. If companies do not know what tariffs they might face, they will be reluctant to expand production or to invest. Indeed, economically, uncertainty acts much like a tax, but without any associated revenues.

Chart 2: Trade policy uncertainty has risen sharply since the beginning of 2025  Finally, in recent weeks, we saw a marked increase in market volatility globally. At the onset of the announcements of reciprocal tariffs, risky asset prices across the world fell sharply. At the same time, we also saw some unusual patterns emerge in markets. Unlike typical ‘risk-off’ episodes, which tend to be associated with falling US Treasury yields and an appreciation of the dollar, yields on US Treasuries rose and the dollar fell in the days following the reciprocal tariff announcements (Chart 3). These patterns are consistent with an increase in the risk premium for holding dollar assets, at least temporarily. Since the start of the 90-day pause on reciprocal tariffs, and more recently the outcome of recent trade discussions between the US and China, we have seen a reversal of some of these trends. But market sentiment remains fragile, amidst elevated policy uncertainty.

Finally, in recent weeks, we saw a marked increase in market volatility globally. At the onset of the announcements of reciprocal tariffs, risky asset prices across the world fell sharply. At the same time, we also saw some unusual patterns emerge in markets. Unlike typical ‘risk-off’ episodes, which tend to be associated with falling US Treasury yields and an appreciation of the dollar, yields on US Treasuries rose and the dollar fell in the days following the reciprocal tariff announcements (Chart 3). These patterns are consistent with an increase in the risk premium for holding dollar assets, at least temporarily. Since the start of the 90-day pause on reciprocal tariffs, and more recently the outcome of recent trade discussions between the US and China, we have seen a reversal of some of these trends. But market sentiment remains fragile, amidst elevated policy uncertainty.

Chart 3: Unusually, during the market volatility in April, the dollar fell and US Treasury yields rose

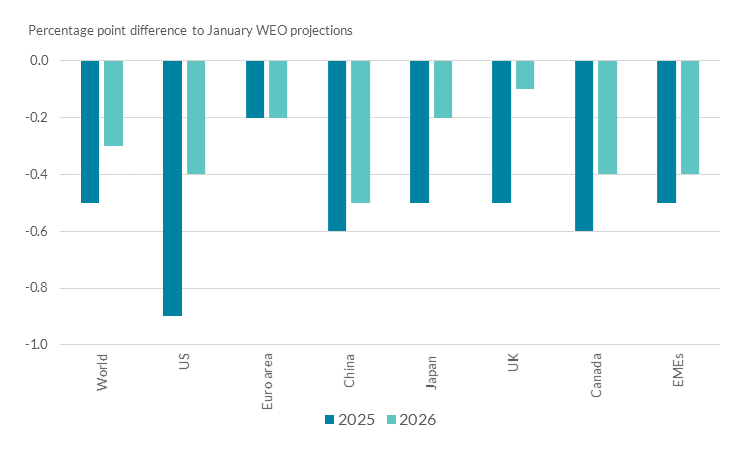

The combination of these factors led the IMF last month – based on information available at the time – to downgrade its global growth projections by around 0.5pp this year and 0.3pp next year (Chart 4). [2] This is not a global recession, but it is a material deceleration in growth, relative to previous expectations.

Chart 4: The IMF has downgraded its global growth forecasts recently

These global shifts will weigh on the domestic economic outlook

So what does this all mean for Ireland? Clearly, given Ireland’s openness to trade and investment – as well as its strong economic linkages to the US – Ireland is particularly exposed to these global shifts and, more broadly, to an increasingly fragmented global economy.

Relative to the size of the economy, Ireland’s trade linkages with the US are the highest amongst EU countries. In addition, US multinational companies play a particularly important role in the Irish economy. Indeed, these two characteristics are related. They both reflect Ireland’s integration into the value chains of US multinational companies.

But I want to go beyond headline measures of exposure to external developments. So let me trace through the transmission channels of these interrelated global shocks – tariffs, uncertainty and the risk of tighter financing conditions – for the domestic economic outlook, and how to think about the respective impact of each for the domestic economy.

Tariffs

I will start with the direct effects of tariffs, not least because this represents a potentially significant structural shift in the global trade policy environment.

As you know, there is still uncertainty around the level of tariffs that may prevail over time between the US and the EU, whether in aggregate or in terms of specific sectors. The US currently imposes a 10% tariff on most EU exports to the US, but with some sectoral exceptions. For example, tariffs on aluminium, steel and auto parts are 25%. Whereas tariffs on pharmaceutical products are still under consideration by the US administration and, for now at least, these are exempt from the 10% tariffs.

Overall, given the make-up of Irish exports, at this stage, US tariffs apply to around 25% of our exports. But this could change, depending on the outcome of the US administration’s deliberations on tariffs on pharmaceutical products or indeed the outcome of the 90-day pause on unilateral tariffs by the US administration. And, of course, the EU could itself retaliate depending on the outcome of negotiations over the course of the 90-day pause.

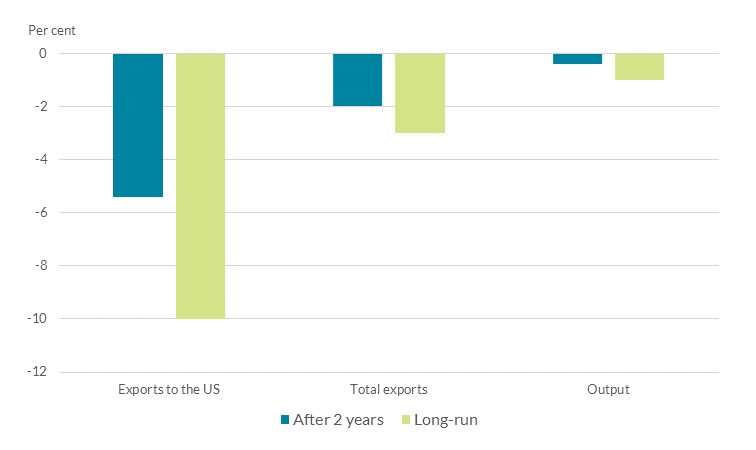

A starting point for understanding the effect of these trade policy shifts on Ireland is through our economic models. There are too many potential scenarios for where tariffs might eventually settle, and I will not attempt to speculate over the ultimate outcome of the various negotiations. But I want to give you a broad sense of the sensitivities in our models. A 10pp increase in tariffs globally would reduce exports to the US by around 5½%, total exports by around 2% and output by around 0.4%, relative to the counterfactual, over two years. The long-run, permanent effects would be around 10%, 3% and 1% respectively (Chart 5).

Chart 5: Permanently higher tariffs will lower Irish exports and output  Of course, all models are a simplification of reality and do not capture all possible channels fully. And, typically, they are calibrated to the average of the past. But we have not experienced as a big of a potential shock to trade policy in decades. So it is important to complement our models with other analysis and consider carefully the different factors that will shape the economic effects of tariffs. Let me outline some of them:

Of course, all models are a simplification of reality and do not capture all possible channels fully. And, typically, they are calibrated to the average of the past. But we have not experienced as a big of a potential shock to trade policy in decades. So it is important to complement our models with other analysis and consider carefully the different factors that will shape the economic effects of tariffs. Let me outline some of them:

- Trade elasticities: A key factor that will determine ultimate macroeconomic outcomes is the responsiveness of trade flows to changes in trade costs, including tariffs. More elastic and substitutable export products are likely to experience a bigger fall in foreign demand, compared to more specialised products that are not easily substitutable. These trade elasticities vary by sector, and also vary over time. Indeed, there is a wide dispersion of estimates of trade elasticities in the literature [3].

- Impact on supply chains and associated FDI: There is uncertainty over how tariffs can affect the functioning of complex supply chains. As I mentioned earlier, we have not had as a big of a shift in trade policy during a period in which the global economy has been so integrated. And this also has implications for associated FDI, which is particularly relevant for Ireland. Indeed, the main vulnerability for Ireland would be if tariffs affected the future path of the foreign-owned capital stock. This vulnerability would be more likely to manifest over time, via the flow of new investment, given adjustment costs in the near term. But the long-run impact of any such shift over time could be material.

- Potential for trade reallocation: Announced tariffs vary, both by origin and product, and these relativities matter. In response to such relative changes, companies may seek to reallocate trade. For example, producers in Ireland may seek to expand into new markets, whether in Europe or further out, as the cost of exporting to the US rises. Similarly, producers in third countries, such as China, may seek to increase exports elsewhere. Indeed, in recent data, we have seen an increase in exports from China to third countries.

- Exchange rate adjustment: The exchange rate will be an important factor in terms of the eventual macroeconomic impact of tariffs. Standard macro models would predict that an increase in tariffs by the US on the rest of the world would result in an appreciation of the dollar. In practice, though, what we have seen is a depreciation of the dollar, and the euro trade-weighted exchange rate rising by 4.5% since end-February.

- Implications for taxable MNE profits: Finally, unique fiscal channels. As you know, Ireland has seen very strong corporate tax receipts in recent years, over and above what would be explained by domestic economic developments (so-called ‘excess’ corporate tax receipts). Tariffs would dent the profitability of certain MNEs, feeding through directly to corporate tax receipts. Any adjustment in the future path of the foreign-owned capital stock would also have implications for corporate tax receipts. These channels are not captured fully in our macro models.

So what is my main message on tariffs? Let me summarise four points:

- First, assessing the impact of tariff shifts on the Irish economy is not straightforward. Put differently, beyond uncertainty over tariff policy itself, there is also uncertainty over the economic impact of tariffs. We know that barriers to trade are costly for everyone. But we also need to recognise that – given the nature of the shocks and the structural evolution of the global economy – history may offer only an imperfect guide to the future.

- Second, with the above caveat in mind, while the direct effect of tariffs will weigh on domestic economic activity, tariffs – on their own – are unlikely to result in a sharp economy-wide shock in the near term, similar to what we saw during the pandemic or the financial crisis. Going in the other direction, though, the potential economic effects are likely more important over the longer-run. Indeed, unlike the pandemic shock, a permanent increase in tariffs would likely lead to a permanently lower level of output than would otherwise be the case.

- Third, there are limits to what aggregate macroeconomic models can tell us, and understanding the effects of tariffs requires taking a sectoral lens. For example, highly specialised pharmaceutical products are likely to be less substitutable and entail higher costs for companies to shift production, given the high investment costs associated with manufacturing facilities. By contrast, exports by the indigenous agri-food sector would typically be more substitutable, seeing a bigger fall in demand for a given tariff increase.

- Fourth, tariffs – and indeed potentially broader policy shifts that could affect the profitability of Irish operations of US multinationals, such as changes to the US corporate tax regime – could have fiscal implications through the impact on excess corporate tax receipts. While the central case around those receipts is – and has always been – particularly hard to gauge, the risks around that have certainly increased.

Uncertainty

Let me know turn to uncertainty. This is a particularly important near-term channel through which external developments are affecting domestic economic activity, and can also have longer-term implications.

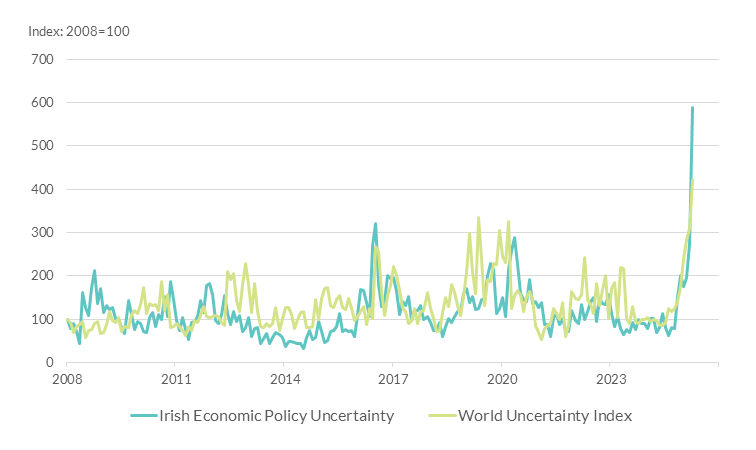

In recent months, we have seen the effects of global trade policy uncertainty translate into significantly higher levels of domestic economic policy uncertainty (Chart 6) . High uncertainty can have significant macroeconomic impacts, by increasing the “option value of waiting”. For example, households may delay purchases of big-ticket durable goods. Similarly, companies might delay – or potentially cancel – new investments. Our engagement with large companies suggests that many have, for now, hit pause on new investment decisions, in light of elevated uncertainty [4]. And this is not just a phenomenon in Ireland, it is a global theme.

Chart 6: Measured economic policy uncertainty in Ireland has reached new highs  Empirical analysis conducted by the Central Bank has sought to quantify the effects of increased uncertainty on economic activity. This shows that increased policy uncertainty has considerable negative effects on domestic demand in Ireland, similar in magnitude to estimates of the effects of uncertainty for other economies (Chart 7). Indeed, on the back of increased uncertainty, we already reduced our forecasts for economic growth in our March Quarterly Bulletin. [5] Since then, economic uncertainty has increased further, so that is likely to further weigh on the economic outlook.

Empirical analysis conducted by the Central Bank has sought to quantify the effects of increased uncertainty on economic activity. This shows that increased policy uncertainty has considerable negative effects on domestic demand in Ireland, similar in magnitude to estimates of the effects of uncertainty for other economies (Chart 7). Indeed, on the back of increased uncertainty, we already reduced our forecasts for economic growth in our March Quarterly Bulletin. [5] Since then, economic uncertainty has increased further, so that is likely to further weigh on the economic outlook.

Chart 7: Estimated effects of uncertainty shocks on the Irish economy

Uncertainty – if it persists – can also have longer-term effects. As an example, in the current context, persistently elevated uncertainty could lead to delayed decisions around investment in manufacturing facilities for new generations of pharmaceutical products. This would have a longer-term effect on the productive capacity of the domestic economy.

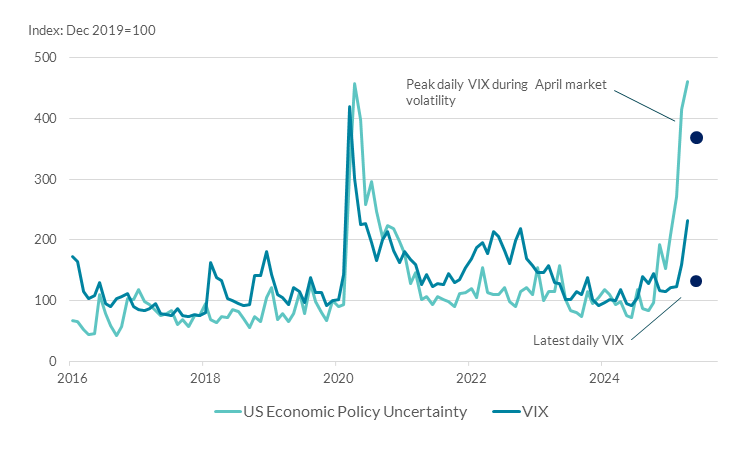

Risk of tighter financing conditions

The final channel is financial conditions. As I mentioned earlier, following the announcement of reciprocal tariffs in April, there was a sharp increase in market volatility. While the tightening of financing conditions has significantly reversed recently, market sentiment remains fragile. Indeed, the previous disconnect between market volatility and economic uncertainty has reopened (Chart 8). An optimal outcome is that this gap closes through a reduction in uncertainty, but there is certainly a risk that it closes through an increase in volatility and a tightening in financial conditions.

Chart 8: The gap between market volatility and uncertainty has re-emerged

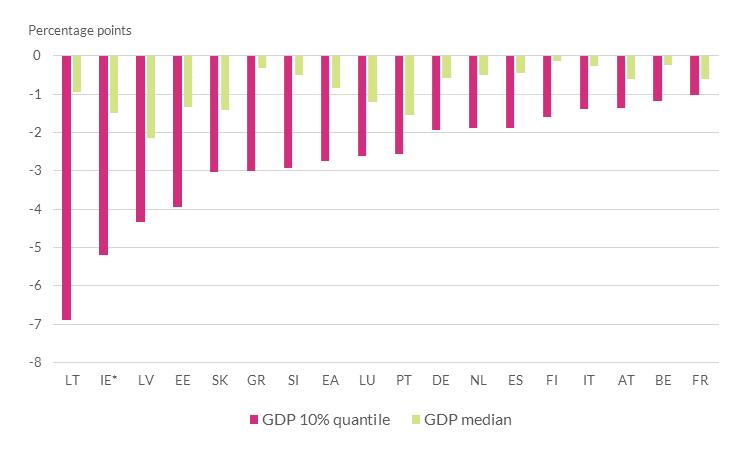

Previous analysis by the Central Bank has quantified the historical sensitivity of Ireland to tighter financial conditions in the US (Chart 9). [6] This shows that tighter US financial conditions lead not only to worse median growth outcomes, but also an increase downside risks to growth. In fact, Ireland shows a stronger sensitivity to US financial conditions than the euro area average.[7]

Previous analysis by the Central Bank has quantified the historical sensitivity of Ireland to tighter financial conditions in the US (Chart 9). [6] This shows that tighter US financial conditions lead not only to worse median growth outcomes, but also an increase downside risks to growth. In fact, Ireland shows a stronger sensitivity to US financial conditions than the euro area average.[7]

Chart 9: Ireland is more sensitive to shocks to US financial conditions than EA peers

Overall, on the external front, these headwinds will weigh on economic activity. As I mentioned earlier, there is uncertainty both over the policy shifts themselves, as well as the economic impact of these policy shifts. At the Central Bank, we are very much focused on the latter. We have pivoted our analytical focus towards understanding the effect of tariffs and broader geoeconomic fragmentation on the Irish economy. And we are complementing our analytical work by engaging with affected businesses, to understand how they are responding to these developments, helping us reduce the fog of uncertainty around the impact of these global trade shifts.

Overall, on the external front, these headwinds will weigh on economic activity. As I mentioned earlier, there is uncertainty both over the policy shifts themselves, as well as the economic impact of these policy shifts. At the Central Bank, we are very much focused on the latter. We have pivoted our analytical focus towards understanding the effect of tariffs and broader geoeconomic fragmentation on the Irish economy. And we are complementing our analytical work by engaging with affected businesses, to understand how they are responding to these developments, helping us reduce the fog of uncertainty around the impact of these global trade shifts.

The economy is entering this period from a strong position, but with underlying vulnerabilities that need to be managed

Let me now turn to domestic developments. Here, the current has been running in the opposite direction, with the economy carrying strong momentum into 2025.

Domestic activity has been growing steadily – and, in our latest projections published in March, we expected that expansion to continue, albeit at a slower rate. Unemployment has been between 4-4.5% recently – and, over the past three years, we have seen the longest extended period of low unemployment back to when data became available in 1983. The headline fiscal position is strong – with the State recording surpluses of over 2% of GNI*. Headline inflation has come down substantially – now standing at around 2.2%. Domestic credit dynamics are neither too hot, nor too cold – with growth in bank credit around 3.5% in nominal terms.

In assessing the Irish economy, however, it is always important to ‘look under the hood’. And, when doing so, it is clear that there are also underlying vulnerabilities in the domestic economy that need to be managed carefully. Let me focus on two areas in particular, which are interrelated.

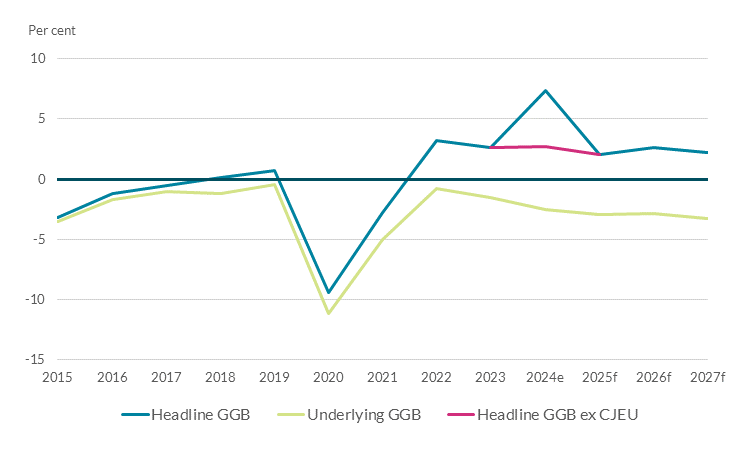

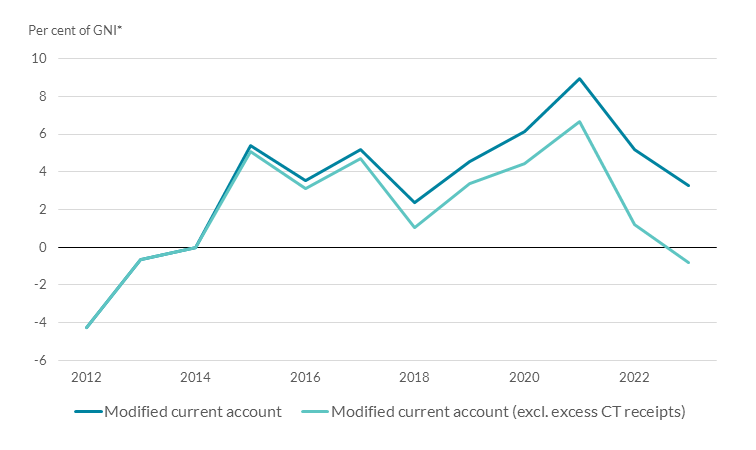

The first relates to fiscal resilience, which is not as strong as suggested by the headline numbers. When estimated excess corporate tax receipts are excluded, the fiscal position swings from a surplus to a deficit (Chart 10). The reliance on corporate tax receipts – specifically, corporate tax receipts from a very small number of MNEs – presents an underlying vulnerability to the Irish public finances, and one that has become more relevant amid a shifting external environment. It is precisely in recognition of this underlying vulnerability that, rightly, the Government has set up the two long-term savings vehicles.

Chart 10: Without estimated excess corporate taxes, the fiscal position would be in deficit

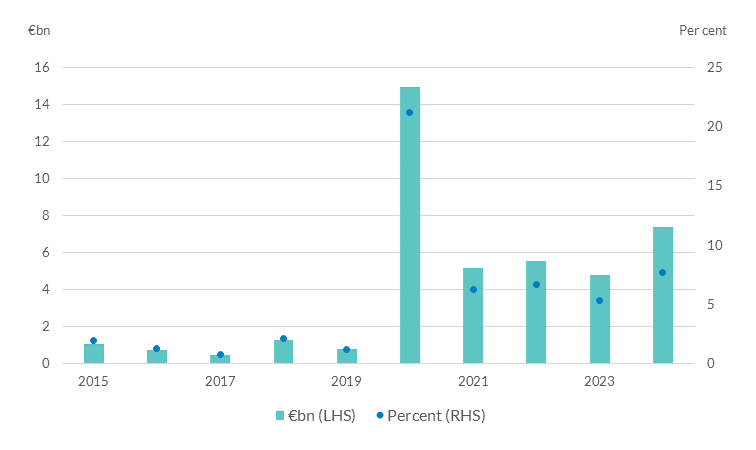

Recent outturns and fiscal projections, however, show that more than a third of these excess corporate tax receipts are flowing through to spending. Indeed, not only has the government been budgeting in excess of its 5% net spending rule, but spending outturns have also been in excess of what has been budgeted for (Chart 11). The outcome has been an overall fiscal stance that has pro-cyclically added to demand in the economy in recent years.

Recent outturns and fiscal projections, however, show that more than a third of these excess corporate tax receipts are flowing through to spending. Indeed, not only has the government been budgeting in excess of its 5% net spending rule, but spending outturns have also been in excess of what has been budgeted for (Chart 11). The outcome has been an overall fiscal stance that has pro-cyclically added to demand in the economy in recent years.

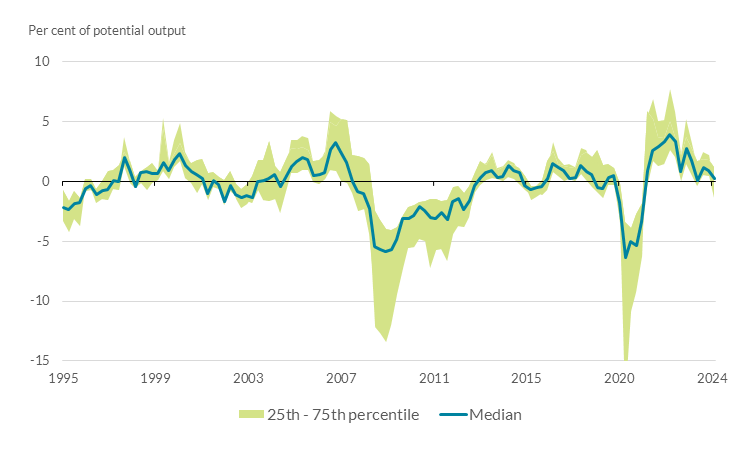

Chart 11: Government spending has exceeded initial budgetary ceilings in recent years  The second area relates to domestic capacity constraints. Here, the assessment is more nuanced. Overall, the estimated aggregate output gap has largely closed, following a period where the Irish economy was clearly operating above capacity (Chart 12). Labour market imbalances have also eased, with demand for labour softening, while the supply of labour has continued to be driven by inward migration.

The second area relates to domestic capacity constraints. Here, the assessment is more nuanced. Overall, the estimated aggregate output gap has largely closed, following a period where the Irish economy was clearly operating above capacity (Chart 12). Labour market imbalances have also eased, with demand for labour softening, while the supply of labour has continued to be driven by inward migration.

Chart 12: The estimated aggregate output gap has closed  Still, critical supply-side constraints remain in terms of infrastructure. This is most obvious in the case of housing, leading to continued strong growth in both house prices and rents. But it is also evident in broader infrastructure deficits, whether in terms of water, electricity or transport [8]. Unless addressed, such infrastructure deficits can harm our competitiveness and productivity, and also contribute to the emergence of broader macroeconomic imbalances. For example, they can act as a constraint on the ability of Ireland to attract labour from abroad, which has been a key factor supporting the supply of labour, amid resilient labour demand in recent years.

Still, critical supply-side constraints remain in terms of infrastructure. This is most obvious in the case of housing, leading to continued strong growth in both house prices and rents. But it is also evident in broader infrastructure deficits, whether in terms of water, electricity or transport [8]. Unless addressed, such infrastructure deficits can harm our competitiveness and productivity, and also contribute to the emergence of broader macroeconomic imbalances. For example, they can act as a constraint on the ability of Ireland to attract labour from abroad, which has been a key factor supporting the supply of labour, amid resilient labour demand in recent years.

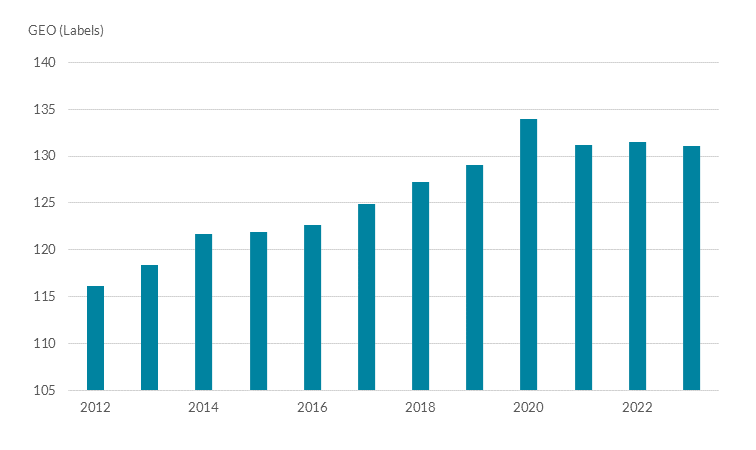

From a broader macroeconomic lens, when thinking about potential imbalances, we would tend to look at indicators such as inflation dynamics or the external position. On the former, headline inflation has fallen substantially, though services inflation has been more persistent. More broadly, measures of comparative price levels of consumer goods and services show that the gap between price levels in Ireland and the euro area has gradually widened over the past decade (Chart 13). [9] On the latter, Ireland of course is running a large modified current account surplus. But, if corporate tax receipts are excluded, the picture on the balance between domestic savings and investment is less favourable than suggested by the headline figures (Chart 14).

Chart 13: The gap between price levels in Ireland and the euro area has gradually widened over the past decade  Chart 14: The modified current account, without excess CT receipts

Chart 14: The modified current account, without excess CT receipts

Overall, the economy is not showing flashing red signs of imbalances in aggregate. But it has been operating at full tilt and infrastructure deficits have become an increasingly important constraint on the supply side of the economy. This undercurrent also requires careful management, to guard against the emergence of imbalances or an erosion of our competitiveness over time.

Policies to navigate cross currents

Let me finish off with a perspective on what this complex environment means for domestic economic policy. Many of the themes that I will cover are not new, but the current landscape is providing additional impetus to these [10].

Ultimately, the uncertain global environment requires being clear-eyed on the risks and laser-focused on the opportunities.

I’ll highlight five areas:

- Commit to a sustainable fiscal anchor. A stable macro-economic environment is a precondition for sustained prosperity of the population and for remaining an attractive destination for foreign investment. In a small, open economy that is part of a monetary union, fiscal policy is a key macro-stabilisation lever. In that context, it is important that the Government adheres to an anchor for budgetary policy, ensuring a sustainable fiscal stance. that operates counter-cyclically. More broadly, from a long-run fiscal sustainability perspective, broadening the tax base remains important.

- Address infrastructure deficits. High-quality infrastructure is a necessary ingredient for achieving long-term, sustainable growth and enhances the attractiveness of Ireland as a place to live and do business. Government policies to support infrastructure development are therefore key to maintaining competitiveness. In a fiscal context, prioritising capital expenditure – within the context of an overall net spending envelope – will be important to addressing infrastructure needs. Non-fiscal levers to enable infrastructure investment are also critical, including to reduce delays in construction of key infrastructure projects [11].

- Contribute to strengthening the EU. An increasingly multi-polar world underpins the importance of strengthening Europe. Enhancing the Single Market and making concrete progress towards a Savings and Investment Union remain essential to boost productivity and support Europe’s shock-absorption capacity. There is also a domestic dimension to these priorities. For example, there is a significant stock of household savings in Ireland and evidence suggests that the household savings ratio is on a gradual upward trend [12]. Yet the share of Irish household savings invested in capital markets remains low. So there are opportunities – including through implementation of the Department of Finance’s Funds Review recommendations – to strengthen retail participation in capital markets in Ireland.

- Enable expansion into new markets and support open trade globally. Preserving openness is crucial for Ireland, given the importance of trade and foreign investment for the domestic economy. So Ireland needs to be a strong voice in Europe in support of efforts to expand the network of free trade agreements. Domestically, public policy can focus on helping indigenous companies access new markets. And this includes the EU single market. Because, ultimately, our domestic market is not one of 5mn people, it’s one of close to 450mn people.

- Safeguard resilience of finance. A more uncertain global environment increases the risks of unexpected shocks. Safeguarding financial and operational resilience of the financial system is a precondition for finance to be able to do its job: supporting households and businesses, through the cycle. Indeed, the resilience built over the past decade means the banking system has acted as a shock-absorber in recent years. At a global and European level, there is increased focus on the potential costs of complexity in regulation. My colleague Deputy Governor McMunn spoke recently about how the Central Bank is thinking about the European simplification agenda [13]. And the fact is that we welcome those efforts. But, as we embrace the opportunities from simplifying the regulatory framework, we are also clear that simplification should not slide into lower standards that would introduce more costs than benefits for society.

Conclusion

Let me conclude. The global environment has been shifting rapidly in recent months. The combination of higher tariffs, increased uncertainty and higher market volatility are weighing on the global growth outlook, and also feeding through to the Irish economy. Going in the other direction, the domestic economy is entering this uncertain period from a position of strength and – if anything – has been bumping up against domestic capacity constraints.

Economic policy needs to steer carefully to navigate these cross-currents. Of course, many of the external shifts are outside of the control of domestic policy makers. But the rapidly changing environment has added further impetus to ‘control the controllables’, helping Ireland meet the challenges and grasp the opportunities to enhance its long-term economic resilience.

[1] I am very grateful to Thomas Conefrey, Patrick Haran, Robert Kelly and Martin O’Brien for their advice and suggestions in preparing these remarks.

[2] See IMF (2025), World Economic Outlook, April 2025.

[3] See, for example, Boehm et al (2023) ‘The Long and Short (Run) of Trade Elasticities’, American Economic Review, Vol. 113, No. 4.

[4] See, Bloom (2009) ‘The impact of uncertainty shocks’, Econometrica, Vol. 77, No. 3,

[5] See Arce and Byrne (2025) “The effect of economic policy uncertainty on the forecast”, Quarterly Bulletin, 2025 No.1.

[6] See Emter (2021) ‘Global financial conditions and downside risks to growth: lessons from past shocks’, Financial Stability Review 1; and Beutel et al (2025) ‘The global financial cycle and macroeconomic tail risks’, Journal of International Money and Finance, Volume 156.

[7] To some extent, this reflects historically average sensitivities, and will implicitly capture the pre-crisis reliance of the domestic banking system to more volatile international financing. This has reduced drastically over the past 15 years. But there are other channels of transmission, for example, in terms of non-bank financing of the domestic economy or the impact of global financial conditions on MNE activities.

[8] See Madouros (2024), ‘Managing the macroeconomic trade-offs of increased investment in infrastructure’.

[9] This measure is based on price surveys covering more than 2 000 consumer goods and services, conducted across 36 European countries participating in the Eurostat-OECD Purchasing Power Parities (PPP) programme.

[10] See Makhlouf (2025), ‘Building economic resilience’.

[11] See Conefrey et al (2024) ‘Fiscal priorities in the short and medium term’, Quarterly Bulletin No.2.

[12] See Boyd et al (2025) ‘The evolution of household savings: determinants and implications’, Signed Article, Vol. 2025, No.1.

[13] See McMunn (2025) ‘Shocks and shifts – regulation and supervision in a changing world'.