Staying the course: monetary policy to avoid persistent inflation - Remarks by Governor Gabriel Makhlouf

04 April 2023

Speech

Remarks at Markets News International Event by Gabriel Makhlouf Governor Central Bank of Ireland and Member of the Governing Council of the ECB

Good afternoon.

The title of my talk today – 'Staying the course – monetary policy to avoid persistent inflation’ – reveals much about my current views on inflation and the near term path for monetary policy.

The latest data suggest that the direct effects of the supply shocks we have seen over the last two years are gradually fading. We see this in the declining rate of headline inflation in recent months.

However, indirect effects are still working their way through the economy as the input price increases we saw last year pass through more slowly into core inflation, and domestic cost pressures emerge in the form of wages and profit margins. Monetary

policy must ensure that this does not become a source of persistent inflation above our 2 per cent target.

To achieve this, the Governing Council decided last month to increase the three key ECB interest rates by 50 basis points. The interest rate applied to our Deposit Facility is now at 3 per cent, up from minus 0.5 per cent last July. This

represents a significant tightening of the monetary policy stance, commensurate with the challenges to price stability we have been facing.

The scale and pace of interest rate increases – up 3.5 percentage points in just nine months – is unprecedented. For comparison, previous rate hiking cycles in the euro area in 1999-2000 and 2005-07 saw rates rise by 2.25 and 2 percentage

points over a 13 and 21 month period, respectively.

Today I will highlight my view on the key factors that will influence the future path of monetary policy. They include both the data I am monitoring, and how I react to this data when making policy decisions.

The first is the assessment of the inflation outlook in light of the incoming economic and financial data, as embedded in the economic narrative underlying the quarterly projections. The second is the dynamics of underlying inflation, as a cross-check

on how the projections compare with the evolving data. And the third is the judgement as to the strength of the transmission of monetary policy to date.

Let me begin with a review of the drivers of core and headline inflation.

The path of headline and core inflation

The sharp increase in headline inflation throughout 2022 stems from both supply and demand factors. On the supply side, overlapping negative shocks from pandemic bottlenecks and the war in Ukraine led to higher costs for firms. On the demand

side, the re-opening of the economy after the pandemic boosted consumer demand at a time when supply was already constrained. The build-up of pandemic savings in parallel with pent-up demand also meant that higher input costs, as a result of supply

shocks, could be more easily passed on to consumers.

The decline in energy prices and the easing of supply bottlenecks in recent months will help ease some of the inflationary pressures as the cost of inputs fall. However, countering this deflationary impulse are more domestically-oriented, demand-related

factors. Underlying the ECB staff March macroeconomic projections is an assumption that above average nominal wage growth will play a central role in inflation dynamics through to end-2025. However, some of this wage growth is expected to be

absorbed into profit margins as the conditions that allowed firms to increase margins during 2022 fade.

Headline inflation in the euro area peaked at 10.6 per cent in October 2022 and fell to 6.9 per cent in March 2023.

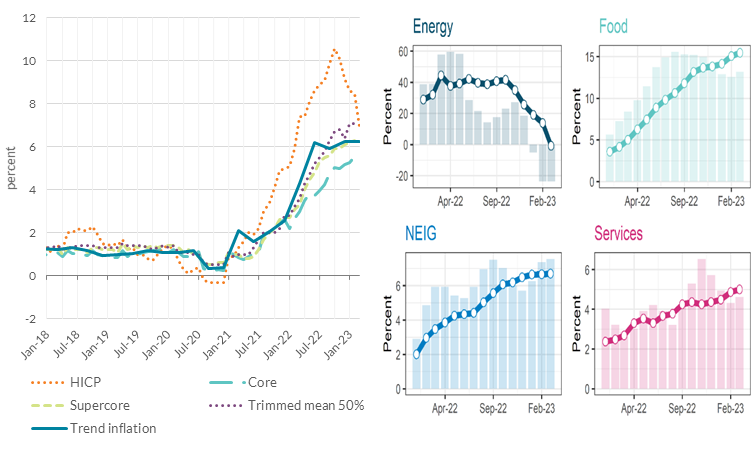

But, while headline inflation has been falling, underlying inflation (as measured by core inflation, i.e., the headline measure excluding food and energy) has continued to increase, rising from 5.0 to 5.7 per cent between October and March. Core

is typically more slow-moving than headline measures, and tells us something about the persistence of inflation over the medium term. As Chart 1 (left-panel) shows, measures of underlying inflation tracked by the ECB and the Central Bank of

Ireland are either trending higher or remain elevated, with the broader range of measures currently between 4 per cent and 8 per cent. Similarly, Chart 2 (right-panel) shows that, while momentum in energy prices has declined sharply in the past

two months, momentum of price growth in the food, goods and services components of HICP remain elevated.

This recent divergence between headline and underlying inflation reflects two factors: first, the delayed pass through of supply-related input cost shocks into core prices; and second, an increasing role for more domestically-driven inflation drivers,

such as wages and profits, as I mentioned earlier. Therefore, a prolonged period of higher wage demands and/or increasing profit margins could drive the persistence of underlying inflation in the euro area.

Absent future shocks to energy and commodity prices, the outlook for inflation over the medium term – the ECB’s 2 per cent target – will be closely linked to developments in underlying inflation.

Let me now discuss the prospects for these dynamics in the context of the broader macroeconomic environment.

Chart 1: Headline and underlying inflation factors

Source: Eurostat and (PDF 1.5MB)Aydin Yakut (2023) (PDF 1.5MB).

Notes: Trend inflation is based on the methodology of

(PDF 1.5MB)Aydin Yakut (2023 (PDF 1.5MB)) (PDF 1.5MB)

. Latest observation for HICP, Core and Trend inflation is March 2023, Supercore and trimmed mean is February 2023. Momentum is defined as the annualised 3 months on 3 months rates, seasonally adjusted data.

Economic outlook and transmission of monetary policy

Given the high uncertainty around the outlook for the economy, my colleagues and I will be especially focused on incoming data as part of making our monetary policy decisions.

The euro area economy slowed in the fourth quarter of 2022, with economic growth stagnant in the face of falling private domestic demand. High inflation, prevailing uncertainties and tighter financing conditions dented private consumption and investment,

which fell by 0.9 per cent and 3.6 per cent respectively. However, the ECB staff March macroeconomic projections envisage a recovery in the next few quarters as supply conditions improve further, confidence recovers, and firms work off large order

backlogs. Rising nominal wages and falling energy prices will partly offset the loss of purchasing power that many households are experiencing as a result of high inflation. This, in turn, will support consumer spending.

Looking ahead, with record low unemployment expected to hold steady at 6.7 per cent, the ECB staff’s current projections embed a significant degree of real wage catch-up, with wages returning to 2022 levels in real terms by end-2025. Nominal

wage growth projections of 5.0, 4.4 and 3.6 per cent in 2023, 2024 and 2025 are significantly above historic averages.

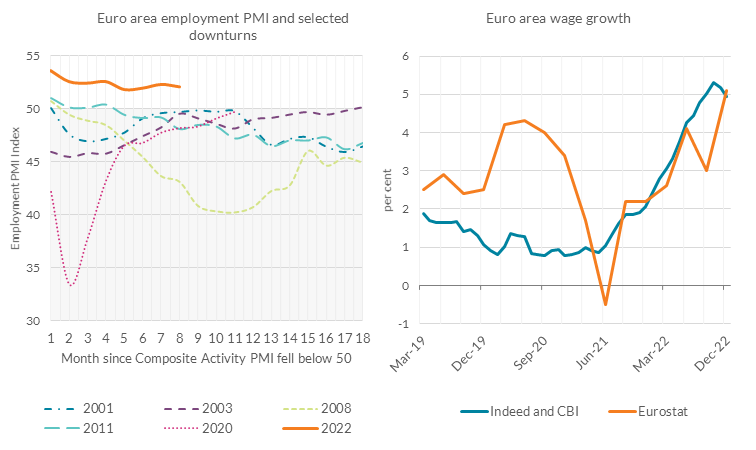

For wage developments, much will depend on ongoing levels of labour market tightness. While the number of job vacancies in the euro area have started to recede gradually since the turn of this year, the number of job openings relative to unemployed

remains at a historic high. Meanwhile, despite the weaker PMI (Purchasing Managers’ Index) data we saw towards the end of 2022, employment expectations remained in significant positive territory (Chart 2, left panel). This suggests

that some degree of labour hoarding is taking place, likely reflecting firms’ expectations of a transitory weakness in demand, as well as their ability to absorb higher costs through increased mark-ups (a point I will return to).

Recent data shows that wage growth accelerated throughout 2022 (Chart 2, right panel). According to Eurostat, wages in the euro area increased by 5.1 per cent in the final quarter of 2022. A wage tracker jointly developed by colleagues in the

Central Bank of Ireland and Indeed shows that hiring wages are growing strongly, with euro area wage growth averaging 4.9 per cent in the three months to end-December. The ECB’s negotiated wage tracker, which incorporates

information on wage agreements in the euro area, shows an average for agreements signed towards the end of 2022 of 4.8 per cent.

Chart 2: Labour Market Developments

Source: Refinitiv, S&P Global, CBI Calculations; Eurostat, Indeed and Central Bank of Ireland wage tracker

Notes: Eurostat data is year-on-year growth and is available quarterly. Indeed data is the three-month moving average and is available monthly.

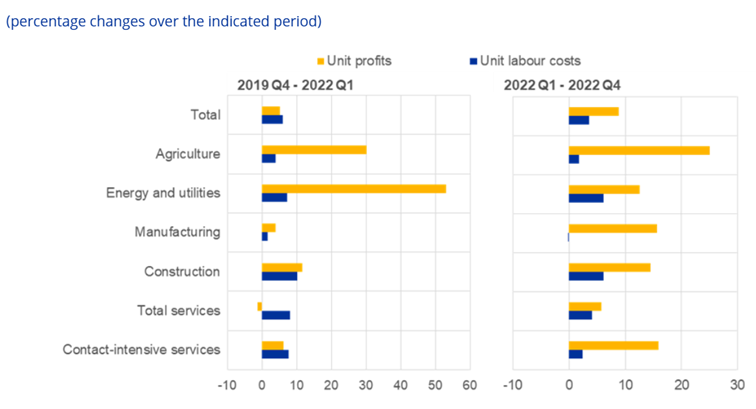

There is potential for profit margins to absorb some of this near-term higher wage growth. As Chart 3 shows, labour costs have not risen by anything close to the same extent as profits in most sectors. For some sectors, the gap between

growth in unit profits and unit labour costs during 2022 is very large, for example in agriculture, manufacturing and contact intensive services.

To the extent that profits and labour costs are a key driver of domestic price pressures, which in turn determine underlying inflation, I will be closely monitoring developments in both areas. The current economic narrative in the March

projections is for a slowing of growth in wages and profit margins over the next three years. If this turns out not to be the case – for example, if we end up in a situation where staggered price and wage-setters engage in

back-and-forth attempts to fully offset real income declines (i.e., a wage-price spiral) – it would call for a stronger monetary policy response in order to mitigate against the risk of this even more persistent inflation.

Chart 3: Sectoral wage and profit developments during and after the pandemic

Source:Arce, Hahn and Koester (2023). Unit profits correspond to gross operating surplus over real value added. Contact-intensive services include trade, transport, accommodation and food services as well as arts, entertainment, recreation and other services. Latest observations: 2022 Q4.

While price and wage-setting will contain a backward-looking element, especially after a supply-driven surge in inflation, it is important that the forward-looking component remains close to our inflation target in order to avoid

an entrenchment of higher inflation in expectations amongst the public. So far, there has been no indication that expectations have become de-anchored from our inflation target. This is true for both survey and market-based measures of longer-term

inflation expectations.

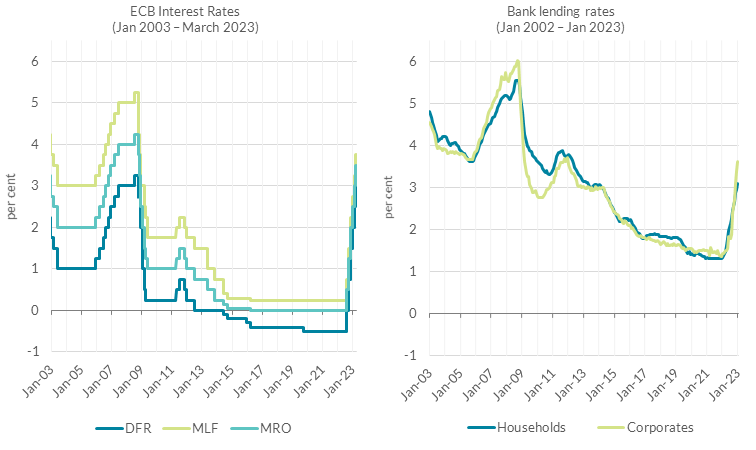

With regards to the transmission of monetary policy, the pass-through into financial conditions is well underway. Interest rates on loans to firms and households increased sharply since the beginning of 2022 (Chart 4). The composite cost for borrowing

for households was 3.1 per cent in January, up from 1.3 per cent at the same time last year. For firms, the composite cost of borrowing rose from 1.4 per cent to 3.6 per cent over the same period. Lending rates have also declined, with the

growth in loans to households falling from 4.5 per cent (year-on-year) in July to 3.2 per cent in February. For firms over the same period, the decline in growth rates was from 7.6 per cent to 5.7 per cent.

Meanwhile, we must remain alert to the longer lags in the transmission of monetary policy to growth and inflation. It will be important to assess how monetary policy decisions to date are working through the economy when calibrating further decisions.

Chart 4: ECB policy rates are being passed through into lending rates

Source: Eurostat. Lending rates are the composite rate, incorporating all loan types and lengths, for both households and corporates.

Conclusion

The Governing Council has increased interest rates in order to counter the increase in inflation brought about by successive and over-lapping supply shocks.

Looking ahead, the ECB staff’s latest (March) macroeconomic projections see headline inflation at 2.1 per cent and core inflation at 2.2 per cent in 2025. This shows that our monetary policy tightening is taking effect, but we must remain steadfast,

and ready to act as required, to ensure we reach our target over the medium-term.

Policy rates will need to be kept at a restrictive level to dampen demand. This will help to re-set the balance between supply and demand in the economy and bring down inflation.

I am monitoring closely recent financial market volatility, but I am also confident that the banking sector is more resilient to a wide range of potential adverse shocks. Short-term volatility in financial markets does not translate into risks for

the macroeconomic outlook, as monetary policy is concerned with achieving price stability in the medium term. Nevertheless, the Governing Council will be mindful of developments in the banking sector, and financial stability more broadly, as we

continue to assess our monetary policy stance.

Ultimately, the primary goal is to ensure our price stability mandate is met. Interest rates will remain the main tool to achieve this mandate. Decisions on interest rates will be made on a meeting-to-meeting basis, with the path calibrated

in-line with the incoming data, notably on underlying inflation trends, and evidence on how the tightening of monetary policy is transmitting to economic activity.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Gillian Phelan, Neil Lawton and Reamonn Lydon for their assistance with this speech.