The economic outlook and monetary policy

11 June 2020

Blog

Last week, I joined my colleagues on the Governing Council of the European Central Bank (ECB) for one of our regular meetings where we set monetary policy for the euro area. I've written about the structure of the Governing Council, our price stability mandate, and our monetary policy response to the COVID-19 crisis in previous posts. At last week's meeting, we decided to strengthen our response to the crisis, in view of developments since our last meeting (in April) and the new macroeconomic projections released by Eurosystem staff (the Eurosystem refers to the National Central Banks of the euro area and the ECB). Our goal remains to support the economy during the current crisis and through the recovery phase, and to safeguard price stability over the medium term.

The Economic Outlook for the Euro Area

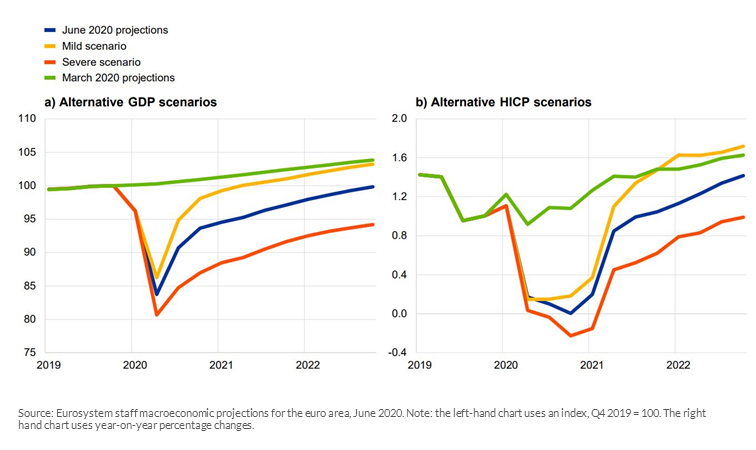

It is clear now that the COVID-19 pandemic has caused a very substantial shock to the global economy. For the euro area, GDP declined by an unprecedented 3.6% in the first quarter of this year, which is a sharper contraction than was seen during the global financial crisis. Higher frequency PMI data shows the sharp contraction has continued through the second quarter. There has also been a sharp deterioration in labour markets across the euro area, feeding through to incomes and to consumption patterns. These developments, among others, have caused sharp downward revisions in the macroeconomic projections for 2020 to 2022 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projection scenarios for 2020 to 2022

These projections have changed greatly compared to the previous set from March, just three months ago. It's not only the numbers that look different in this round of projections; there has also been a change in how we present the uncertainty surrounding the key forecasts. Previously, we calculated ranges around our central forecasts of GDP and inflation based on how well our models have performed in recent years. However, as these historical projection errors cannot reflect the current significant uncertainty, a scenario analysis is used to show potential alternate paths for the economy.

In the baseline scenario, there is an assumption of some resurgence in infections over the next couple of quarters that leads to ongoing containment measures, although not as stringent as the initial ones. The economy is expected to “re-open” gradually, in phases, through a post-lockdown transition period, which ends by the middle of 2021. At this point, it is also assumed that medical solutions to contain the virus become available.

Two alternative scenarios serve as an illustration of the wide range around the baseline scenario. The mild scenario assumes that the virus is successfully contained in the post-lockdown transition period and there is no resurgence in infections. As a result, the economy recovers gradually towards normal levels of activity. In contrast, the virus makes a strong resurgence under the severe scenario and strict lockdown measures are therefore extended. These are assumed to be more damaging to economic activity than under the baseline scenario with lower real GDP growth and more subdued inflation (Figure 2). It is worth noting that the effect of the pandemic on inflation dynamics is ambiguous due to competing effects which could cause inflation to increase or decrease. The downturn in the economy will result in substantial economic slack, which would tend to weaken inflation. But the pandemic has also caused supply chains to be constrained and this would tend to drive prices up. Overall, it is likely that that the substantial economic slack will dominate and result in weak inflation dynamics over the medium-term.

Figure 2: Paths for euro area real GDP growth and inflation under macroeconomic scenarios

Aside from considering the effects of COVID-19 on inflation, we also have to consider its effects on how we measure inflation. The pandemic has changed the current expenditure profile of the average consumer. Spending in some sectors such as transport and hotels has dropped dramatically, while others such as groceries have risen sharply. And, as we know, the imposition of lockdowns across Europe has meant many shops have been closed and people have had to stay at home. These factors have complicated the collection of data to assess how prices are changing across the euro area.

This means that there is potential for households to experience price changes that differ from the measured rate although the issue of how consumers understand consumer price inflation in general is not new. A recent piece of research (PDF 1.3MB) from the Central Bank examines how euro area households perceive inflation and finds some interesting results, such as that consumers may find it difficult to adjust observed prices for changes in the quality of goods and services when assessing the rate of inflation.

In general, the ECB's baseline projections for growth are below those of other forecasters1, with the exception of the OECD forecasts that were published on Wednesday. All forecasters acknowledge the prevailing very high levels of uncertainty. The OECD has produced two scenarios. In their "single-hit" scenario, the current containment measures are assumed to be largely successful in containing the outbreak allowing a gradual recovery in growth and employment over the remainder of this year and in 2021. In the "double-hit" scenario, there is a second peak of infections in the autumn. The level of GDP in 2021 in the ECB baseline scenario is roughly the same as the OECD's "single-hit" scenario.

The June Monetary Policy Decision

The Governing Council took a number of decisions last week to ensure that the monetary policy stance is appropriate to achieve our price stability objective over the medium-term. The decisions reflected the downturn in the economy and the deterioration in the outlook for growth and inflation. In particular, we see it as important for monetary policy to maintain favourable financing conditions for all sectors of the economy and across countries, as the demand for credit is strong given the significant liquidity issues many firms are facing. We need to avoid an unwarranted tightening of financial conditions and for lending to the real economy becoming constrained.

So the first decision taken by the Governing Council was to increase the envelope of asset purchases under the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) by €600bn to €1,350bn. The PEPP will contribute to an easing of the monetary policy stance and help to maintain supportive financing conditions for the real economy. These purchases will be conducted in a flexible manner over time, across asset classes and among jurisdictions, to avoid risks to the smooth transmission of monetary policy.

The horizon for the asset purchases under PEPP has also been extended at least until the end of June 2021. We will continue with them until we judge that the COVID-19 crisis phase is over. And when securities purchased under PEPP mature, the principal payments will be reinvested at least until the end of 2022. As we've said before, the Governing Council will adjust the monetary policy stance further, if we decide it is necessary.

Developments in the Irish Economy

Let's look at the domestic economy. Back in April, we published a scenario for the Irish economy in 2020. We noted then that we were experiencing a period of exceptional uncertainty and that COVID-19 had triggered an extremely severe economic shock that was fundamentally different in nature and scope from the type of shock we had seen previously. We are now preparing our next set of projections – to be published in early July – in line with the ECB scenarios.

Since the publication of the projections in April, the downturn in economic activity has been severe. National Accounts data show that consumption declined by 4.7 per cent in the first quarter of the year, following the introduction of strict containment measures. And, although the phased reopening of the economy has started, a further significant decline is expected for the second quarter.

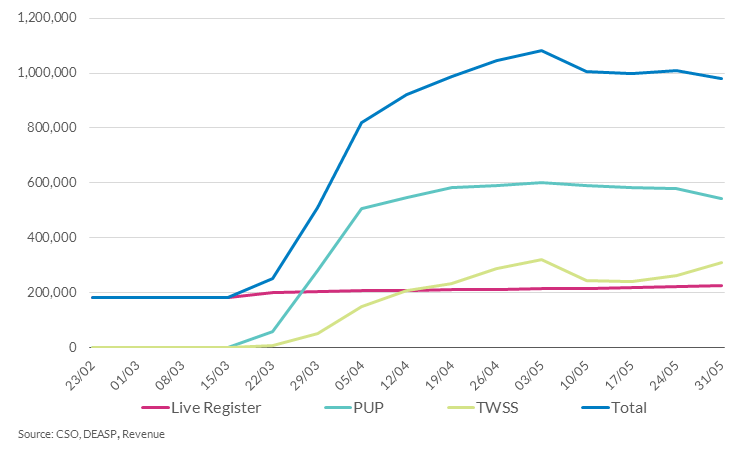

The decline in employment in March and April is unprecedented, with all sectors of the economy affected. Job losses came in waves, with 515,000 people now in receipt of the Pandemic Unemployment Payment, with a further 380,000 now in receipt of the temporary wage subsidy scheme (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Numbers in receipt of state payments by scheme

A standout aspect of the impact of the pandemic has been the pace at which economic conditions nosedived from the onset of the virus. The measures put in place to contain the virus, such as curtailment or full closure of some sectors and limits on travel and social gatherings, had an immediate effect on activity. For analysts and policymakers, this presents a challenge since many key indicators used to monitor economic activity are only released with a lag. For example, official Irish National Accounts data on consumer spending and investment for the period April–June 2020 is not due to be published until September 2020.

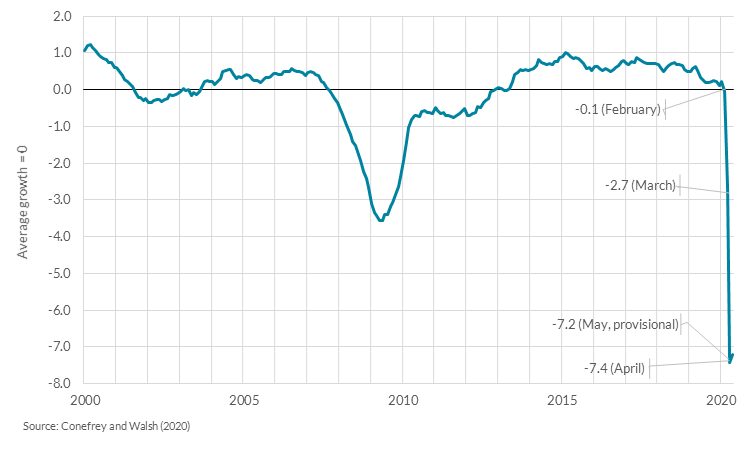

To provide an up-to-date assessment of economic conditions in real time, the Central Bank has developed a Business Cycle Indicator (BCI). The BCI is a monthly summary indicator of overall economic conditions estimated from a larger dataset of high-frequency releases. This week our economists published research (PDF 790.91KB) containing the latest update of the BCI. The analysis shows that it dropped to a record low at the peak of the containment measures in April, as shown in Figure 4. The decline in the indicator in April suggests that the initial economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic was both sharper and deeper than the financial crisis of 2008/09. The latest preliminary estimate of the BCI for May 2020 points to some stabilisation in economic conditions, but the overall level of activity remains substantially below that observed prior to the COVID-19 outbreak.

Figure 4: Business Cycle Indicator (BCI), 2000–2020

World Environment Day

Before I finish, I just want to highlight that last Friday's World Environment Day saw the publication of Business in the Community Ireland's second report on their Low Carbon Pledge, to which the Central Bank is a signatory, as part of our commitment to tackling climate change.

Our participation in the Low Carbon Pledge is a tangible demonstration of our commitment to being a socially responsible and sustainable organisation

At this time of crisis and as the Bank plays its role in maintaining stability and protecting the community, we are also seeking to support a more sustainable economy and reduce not only our own environmental impact but to encourage other organisations to do the same.

Gabriel Makhlouf

1 European Commission, spring 2020 EC forecast; IMF World Economic Outlook, 6 April 2020; Consensus Economics, 11 May 2020; ECB's Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF) conducted between 31 March and 7 April.

Read more