The gap is around +1.5 percentage points, and inflation developments explain the vast majority of it. The key issue here is there is nothing like the 2022-23 inflation surge in the data used to estimate this model (2000-19).7 One reading of this is that the high inflation in 2022 was largely unexpected by wage earners, and it may take longer for the pass through of higher consumer prices to earnings growth than had higher inflation been expected, leading to a delayed adjustment of real wages over time. Of course, the speed and extent of this real wage catch-up also depends on the evolving economic backdrop.

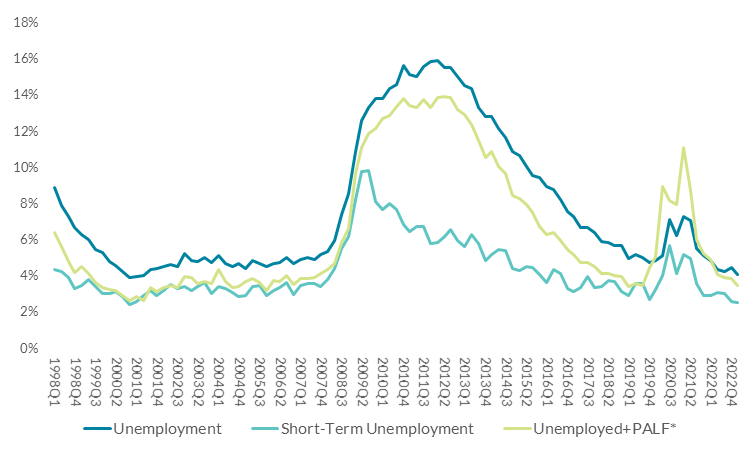

Figure 6: Labour market slack: Unemployed+PALF*

Source: QB article, based on CSO data.

The unemployment plus PALF tightness metric in this Philips curve estimation is largely from the supply side. However, as tightness is also about the balance of supply and demand, we need to consider labour demand.

The job vacancy rate, which increased sharply around post-pandemic re-opening (Figure 7), is one measure of labour demand. In recent months, job vacancies have fallen slightly from post-pandemic highs, which suggests an easing of labour demand. However, the job vacancy rate and the number of job openings remain above pre-pandemic levels.

Figure 7: Job vacancy rate

Source: Eurostat to 2023 Q1. Indeed for Q2 and Q3 2023. Seasonally adjusted.

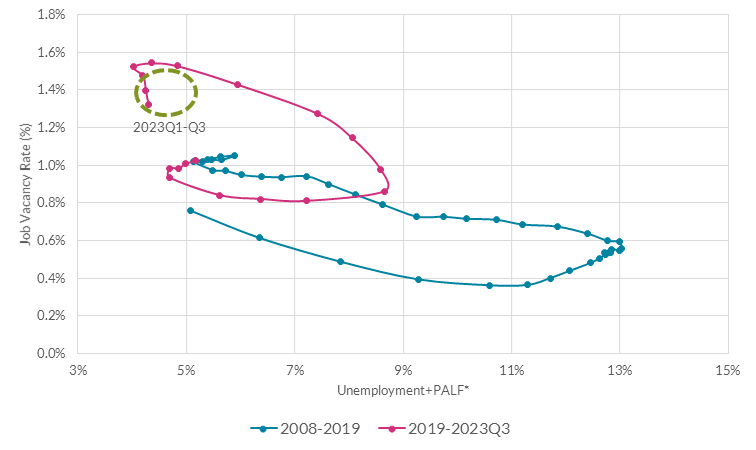

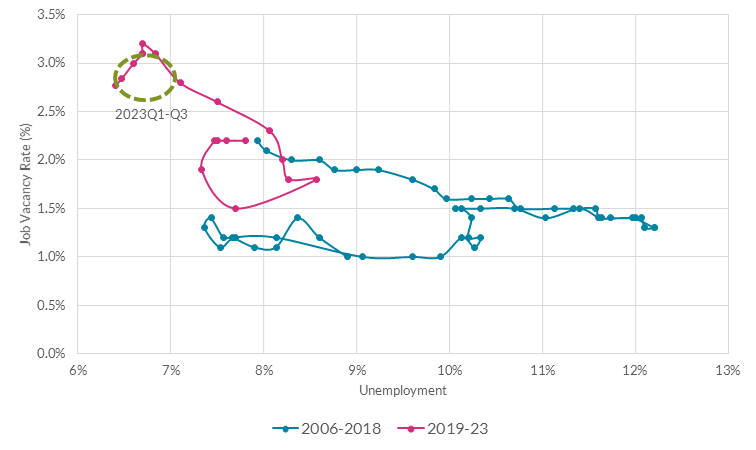

Job vacancies and unemployment tend to have an inverse relationship, as plotted in the Beveridge curve. Cyclical economic variation is marked by movements along the curve, whereas structural changes – such as a change in job matching efficiency – shift the position of the curve. The growth in vacancies that we have observed, alongside falling unemployment during 2022/23, point to cyclically strong labour demand as the main driver of labour market tightness.

Figure 8: Beveridge Curve

Figure 8a: Ireland

Figure 8b: Euro area

Source: QB article and Eurostat. Indeed data on job openings for Q2 and Q3 2023.

The recent fall-off in job vacancies – albeit from a very high level – suggests that tighter monetary policy is beginning to slow demand. However, it will take time for the full impact to become clear and monetary policy will need to remain restrictive for some time before we can be confident we are on the right path.

Before moving on to our latest monetary policy decision, I want to touch on the issue of trade-offs in the context of disinflation and labour market dynamics.

Historically, the slope of the Phillips curve described the trade-off between unemployment (or slack) and inflation. However, recent work that includes the vacancy to unemployment ratio (‘VU-ratio’) in the Phillips curve raises the important question of whether an easing in labour demand occurs mostly at the hiring margin – in other words, fewer job openings – or whether unemployment also rises.8

In the US, which started its hiking cycle earlier than the euro area, the adjustment so far has been mainly through a reduction in job openings. At the same time, job switching, an important driver of wage growth dynamics there, have fallen back to pre-pandemic levels.9 Wage growth has also slowed markedly in recent months.

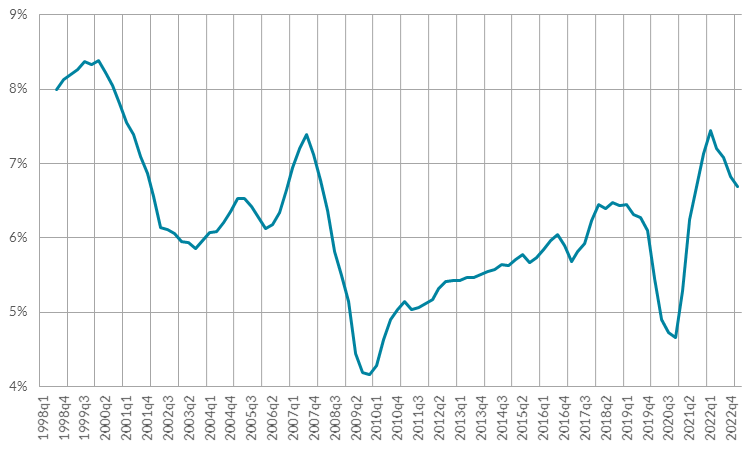

For Ireland, we only have a short time-series of job vacancy data, so it is difficult to compare changes in the VU-ratio over previous cycles. However, recent job hiring statistics show that the post-pandemic surge peaked in the first half of 2022, and has since fallen back (Figure 9). Along with the decline in job openings, this is further evidence of some weakening of the demand momentum that built up after re-opening. However, at 6.7 per cent (of total employment) in Q1 2023, the new hiring rate remains above its long-run average of around 6 per cent.

Figure 9: New hires (Ireland, as per cent of employment)

Source: Labour Force Survey (CSO). New hires are defined as workers with job tenure of three months or less in a given quarter.

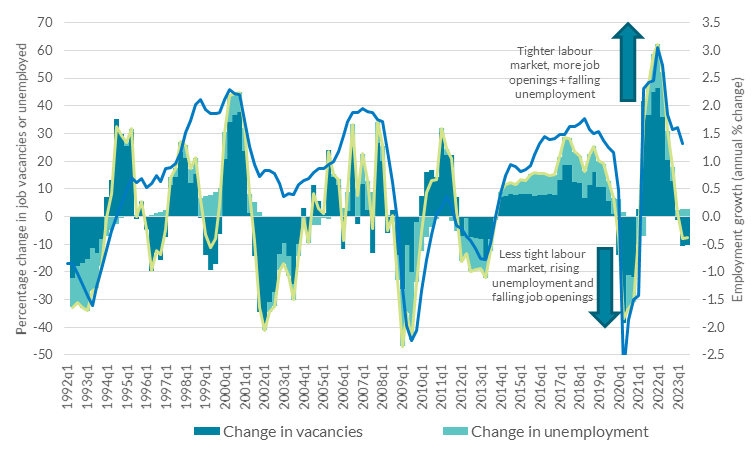

For the euro area as a whole, we can construct a longer VU-ratio time series back to the early-1990s. Decomposing changes in the VU-ratio, a number of stylised facts emerge (Figure 10). First, cyclical variation in the employment rate are typically accompanied by changes in both job vacancies and unemployment (moving in opposite directions). That said, there are some cyclical slowdowns where job vacancies declined but unemployment did not rise, for example in the mid- and late-1990s. The dot-com bust, which shows up as below-trend employment growth during 2002-03 is another episode where job vacancies accounted for the bulk of the change in the VU-ratio, although unemployment also rose slightly during this period. The main lessons I draw from the data is that cyclical slow-downs in employment growth are often accompanied by fewer job openings and higher unemployment. Having said that, ‘soft-landings’ – that is where unemployment does not materially rise – are possible, especially in shallower and shorter slowdowns.

Figure 10: Ratio of vacancies to unemployed persons (euro area)

Source: Eurostat from 2006 onwards. Prior to 2006, the VU-ratio is imputed from data on labour shortages collected by the European Commission.

Recent monetary policy decision and the outlook

While we quickly saw the impact of our monetary policy tightening in financial markets and bank interest rates even before policy started to rise last year, the effects on economic activity have become more apparent in recent months. People and businesses are taking out fewer loans, which will impact consumption and business investment, dampening aggregate demand.

However, despite recent falls, inflation remains too high. Therefore, in order to reach our 2 per cent target in a timely manner, and reinforce the progress we have made towards achieving this target, the Governing Council last week raised its key interest rates by a quarter of a percentage point.

The deposit facility rate now stands at 4 per cent, up from minus 0.5 per cent in July 2022.

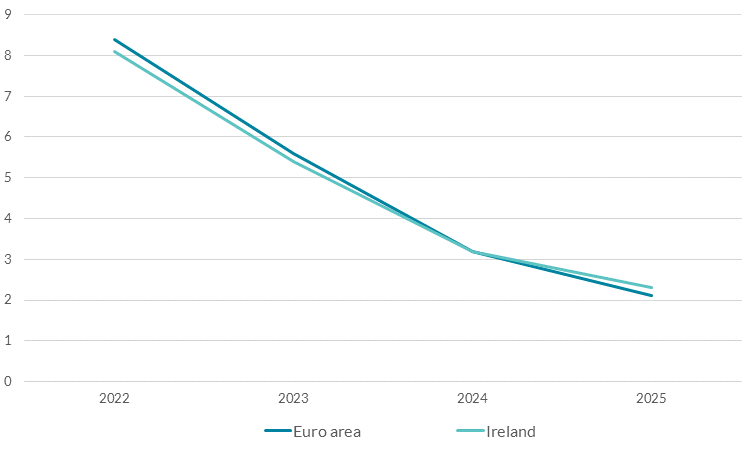

The ECB staff macroeconomic projections see average inflation at 5.6 per cent in 2023, 3.2 per cent in 2024 and 2.1 per cent in 2025. Underlying, or core inflation is expected to average 5.1 per cent in 2023, 2.9 per cent in 2024 and 2.2 per cent in 2025. For Ireland, our own Quarterly Bulletin projections, released earlier this week, show a similar disinflation path (Figure 11). In both cases, the core inflation projection is under-pinned by historically strong wage growth.

Figure 11: Inflation projections to 2025

Figure 11a: Headline inflation (HICP)

Figure 11b: Core (excl. food and energy)

Source: ECB and Central Bank of Ireland.

Relative to the June projections, the main change in the ECB staff projections was the downward revision to euro area growth. Growth in 2023 is now expected to be 0.7 per cent (down from 0.9 per cent) in June. But the major revisions were for 2024 – 0.5 per cent down from 1.5 per cent – and (less so) 2025 – 1.5 per cent, down from 1.6 per cent.

The downgrade of the short-term euro area outlook reflects weaker survey indicators, such as indicators of future orders and employment growth, tighter financing conditions and the stronger euro exchange rate since June. Although there has been some reversal of the latter since the decision last week.

For Ireland, our projections for growth in modified domestic demand in 2023 have been also revised down, from 3.7 per cent to 2.9 per cent, while the 2024 (2.6 per cent) and 2025 (2.3 per cent) profile is broadly similar to our June projections.

Reflecting the growth slowdown, employment growth for the euro area has also been revised down. It is expected to be roughly flat in the second half of 2023, and to average just 0.2 per cent in 2024 and 2025. This is a significant downgrade from the June projections of 0.5 per cent (2024) and 0.4 per cent (2025). It also represents an extended period of below trend employment growth for the euro area (trend growth in employment for 2014-19 was 1.4 per cent), and is consistent with the monetary policy stance remaining tight throughout.

For Ireland, employment growth in 2023 has been upgraded from 2.5 per cent in our June Quarterly Bulletin to 3.7 per cent in September numbers. This change reflects strong Labour Force Survey figures for Q2 2023. Employment growth of 1.7 per cent and 1.5 per cent in each of 2024 and 2025 is broadly similar to the June projections. The lower growth rate in 2024 reflects both supply and demand factors (including tighter monetary policy). On the supply side, we anticipate constraints beginning to bite as our measure of slack (unemployment+PALF) remains historically low, as well as lower migration due to ongoing housing supply issues.

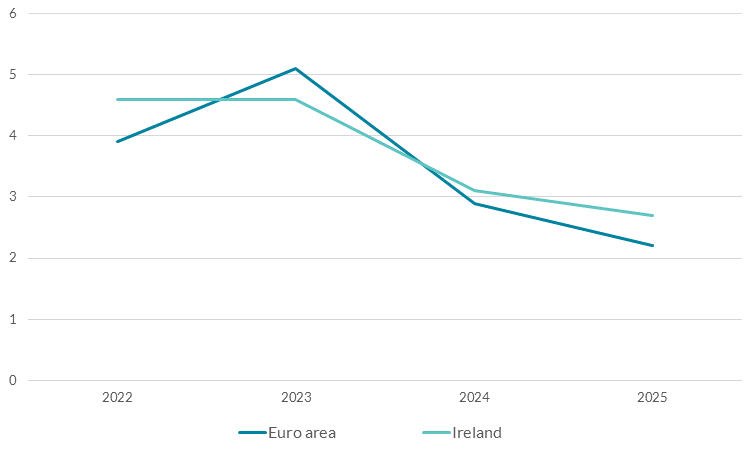

The projections include a small uptick in the unemployment rate in the euro area, rising from its current historical low of 6.4 per cent to 6.7 per cent in 2025. For Ireland, we expect it to remain low throughout the projection horizon, at around 4.3 per cent. Given the expected slowdown in employment growth, this means a likely further decline in job vacancies in the coming months. Despite this, the combined effects of low unemployment and real wage catch-up will contribute to strong wage growth significantly above historical levels, especially for the euro area (Figure 12).

Figure 12: Nominal wage growth

Figure 12a: Euro area

Figure 12b: Ireland

Source: ECB and Central Bank of Ireland. CPE is growth in compensation per employee (CSO); Negotiated wages is from the ECB-SDW; EHECs wage growth is from the CSO; and IWGT refers to the ‘Indeed Wage Growth Tracker’ (see Adrjan & Lydon, 2022 (PDF 841.17KB)).

These wage growth forecasts underpin the underlying (core) inflation projections, for both Ireland and the euro area. If wage growth turns out to be weaker, then we may see a faster decline in core inflation than currently envisaged. If it turns out to be stronger, then the core inflation will prove stickier.

How is it that core inflation is projected to decline, even in the face of historically high wage growth? The answer is that other factors are expected to exert downward pressure on core inflation over the projection horizon, falling input costs from non-labour factors as supply chains normalise, lower profit margins and rising labour productivity.

To conclude, I want to outline what I see as the key risk factors around these wage projections.

On the upside, I see two potential upside risks. One is a more resilient labour demand. And to monitor this I will be closely following both employment growth and job vacancy statistics.

The second is inflation expectations – not something I have paid attention to in my speech today, but nonetheless important. The experience of the 1970s taught us the importance of inflation expectations for wage and price dynamics. In the euro area, expectations increased with the recent surge in inflation, although recent data points to a gradual return to our 2 per cent target for short-term consumer inflation expectations, and medium-term expectations remaining anchored around our 2 per cent target. The anchoring of medium-term expectations plays an important role in our projected disinflation path.

On the downside risks to wage growth, I primarily see one: downside risks to economic growth itself. As we saw in the historical analysis of vacancy-unemployment dynamics, a longer and deeper slowdown could lead to a bigger increase in the unemployment rate, which will put downward pressure on wages. To monitor this, I will be paying close attention to monthly unemployment dynamics, softer indicators such as PMI employment expectations, and wage trackers, such as that developed at the Central Bank of Ireland in collaboration with Indeed. I will also be listening closely to what companies in Ireland and the euro are tell us as part of our regular market intelligence gathering exercises.

As you can see, there are many factors that go into our monetary policy decisions. At each of our six-weekly meetings, the Governing Council assesses what the available evidence tells us about the path for underlying inflation and the transmission of our monetary policy to-date. This is the essence of what ‘data dependent’ means, and it brings me to my final point.

One aspect of our recent decision that has received some attention was the statement that “key ECB interest rates have reached levels that, maintained for a sufficiently long duration, will make a substantial contribution to the timely return of inflation to the target”. Substantial does not mean complete and this should not be interpreted as an unconditional commitment that we have reached the so-called ‘peak rate’ in this hiking cycle. It is the Governing Council’s current view of the monetary policy path based on what we are seeing in the data right now, and our recent projections, a view that could change if some of the risk factors that I have highlighted materialise.

This is the essence of our “data-dependent approach to determining the appropriate level and duration of restriction”. As our statements have made clear for some time: “interest rate decisions will be based on [the Governing Council’s] assessment of the inflation outlook in light of the incoming economic and financial data, the dynamics of underlying inflation, and the strength of monetary policy transmission.”

Thank you.10